“Afrofuturism has become a kind of label or a contemporary art aesthetic”

Josèfa Ntjam is an artist who works in sculpture, photomontage, film and sound. Born in 1992 in Metz, France, she currently lives and works in Saint-Étienne, west of Lyon. Following music conservatory training at a specialist high school, Ntjam studied at ENSA Bourges, which allowed her to spend a year taking political theory classes at Dakar’s Cheikh Anta Diop University. She then completed another master’s degree at ENSAPC, Cergy (known as a ‘laboratory for artistic practices’), from which she graduated in 2017. Given the artist’s varied education, it’s not surprising that she mines from a diverse range of sources. Touching on political history, art history, science, philosophy, ancestral cosmologies and music, her works imagine new and mindbending worlds that are in the lineage of speculative fiction, fantasy comics or worldbuilding computer games. This has been a breakout year for Ntjam. Her participation in the LVMH Métiers d’Art residency resulted in a solo show at the private foundation in Paris, which opened in March. Une cosmogonie d’océans featured 12 sculptures informed by Central and West African mythology – otherworldly, hybrid creatures that had been fabricated by artisans employed by the luxury goods conglomerate, more accustomed to making buckles, rivets and eyelets for the fashion industry. Another solo exhibition, at Fotografiska New York, Futuristic Ancestry Warping Matter and Space-time(s), included a multisensory video experience, biomorphic sculptures and photomontages printed on plexiglass and aluminium, with references ranging from the television series Battlestar Galactica (1978–79/2004–09) to the novels of Octavia E. Butler. For the Venice Biennale, LAS Art Foundation commissioned the artist’s most ambitious work to date: an epic film shown on a vast curved screen that combined computer and hand-drawn animation with photomontage and AI. The work is based on two creation stories in which the deep sea and outer space merge: the Dog on myth of Amma, the sky deity who made the stars, as well as Nommo, the ‘master of water’; and a Huaorani tale about a snake that eats the stars, which turn into the first waterways and marine life. Corresponding with these components was an otherworldly soundtrack played from a series of sculptural listening booths shaped like jellyfish. Ntjam’s retelling of these myths involved layering 3D models of marine life with scans of Amma and Nommo statues (found in Western museum collections) and photographs of figures involved in colonial independence movements. Decolonial histories joined forces with a fantastical vision of the future.

ArtReview Can you tell me about the cover image you made for this year’s Power 100 issue? It features a painting of the revolutionary Toussaint Louverture holding the Haitian constitution.

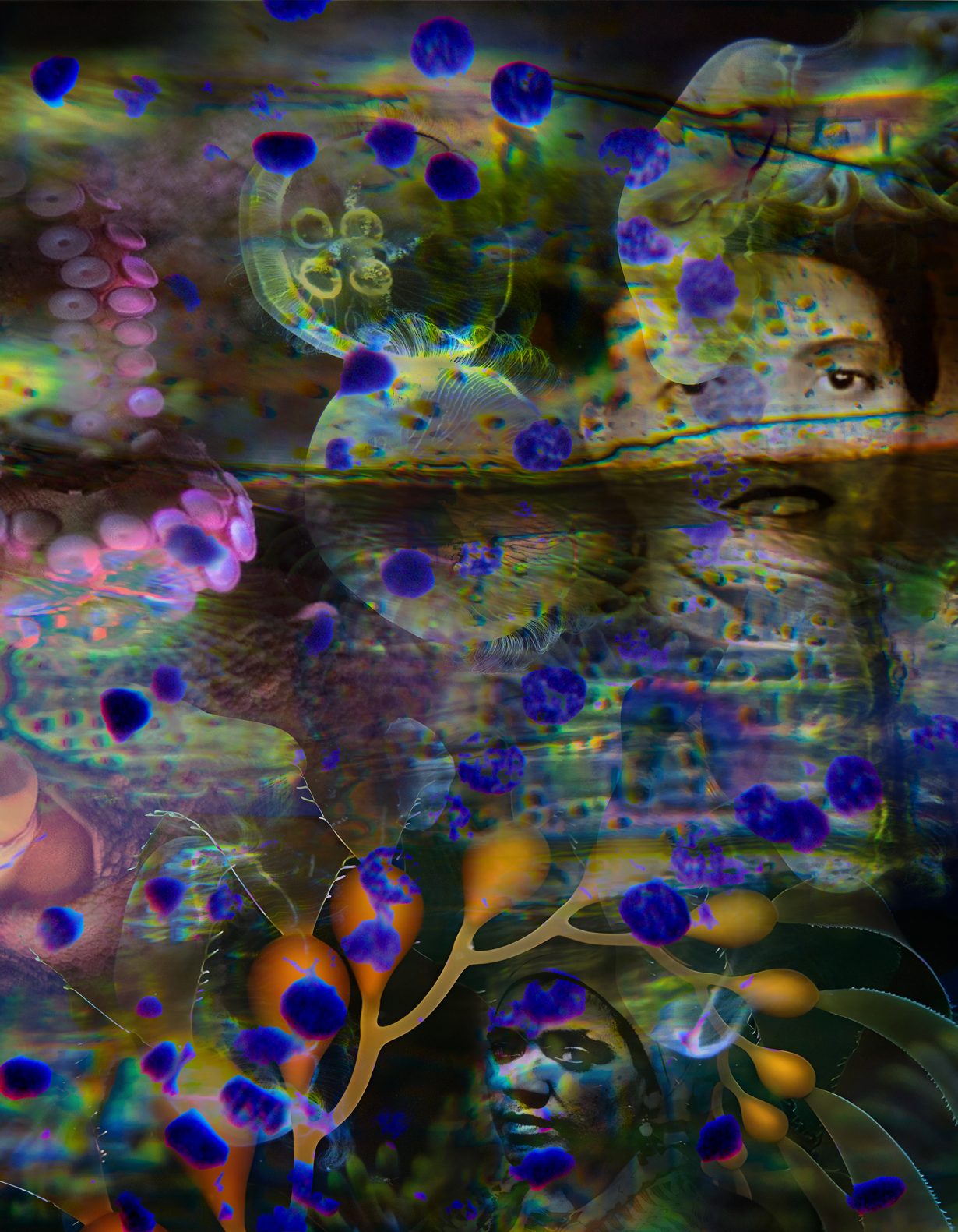

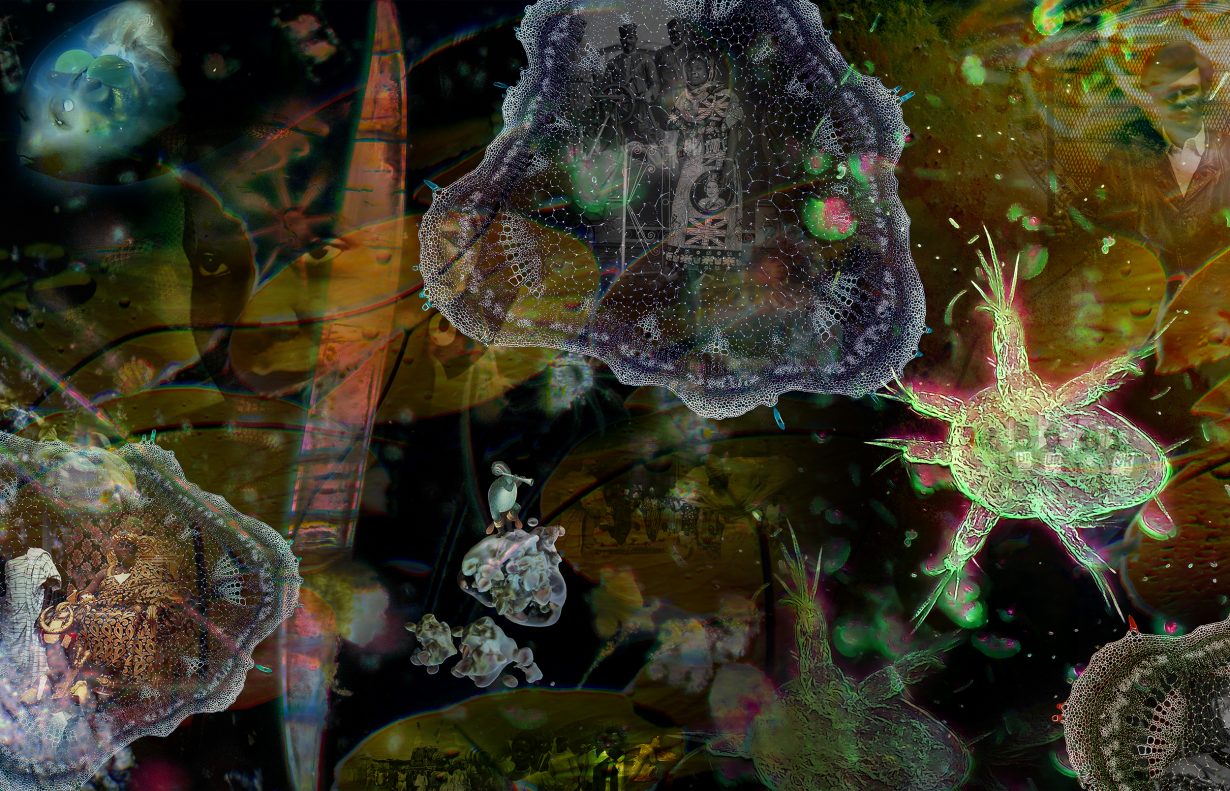

Josèfa Ntjam When I am making photomontages, I mostly work with images of powerful Black people who fight against power, mostly colonial powers. Louverture is a powerful figure but this image also features him holding the Haitian constitution, a document that is itself about power. But contemporary art is about power too, and in this image you have the Bishop, praying, and maybe he could be an allegory for the belief in art, praying to the art God, but I want to make that god a monstrous god. The work is not specifically about Haiti of course, an island still today controlled by a colonial power, but about the nexus of revolutionary Black people. For me the work lies in giving new life to this picture, placing it within a new radical ecosystem, and for that I layer such images within an underwater ecosystem. So much of Black memory lies lost at the bottom of the ocean, specifically because of the slave trade and colonialism, that these watery worlds are a way of resurrecting that. It is a reference also to Drexciya, which was a Detroit techno group, who imagined in their music the underwater country of Drexciya, in which lived the unborn children of the enslaved African women who died crossing the ocean [thrown from the ships because they were pregnant]. So this is a thing also.

AR Your project runs throughout the issue, and features other figures of Black resistance and revolt; people like Elisabeth Djouka, the Cameroonian independence fighter who was active during the mid-twentieth-century anti-colonial struggle and died earlier this year.

JN My methodology of photomontage is really based on how I think, mapping a tentacular infrastructure, in which stories or people are interconnected by intertwined roots and membranes. At school the professors taught history in a fragmented way, but there are so many connections. The fact that you have Elisabeth Djouka coming from the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon, who were being helped by the Communist Party in France, at the same time that the Black Panthers came to Algeria to take part in the fight for their independence. So you have these interconnections of Black diaspora that spread across the world. With these connections, and through multiplication of images into a single frame, I want to visualise an ecosystem. Photomontage allows me to fight a linear understanding of history, and through the layering of imagery to create a network, a rhizomatic imagining of history. It is a geological process.

AR Your family are from Cameroon and took part in the independence struggle too.

JN Yes, I dig a lot of pictures out of archives, but for Cameroon it is often a struggle, because we don’t have a lot of documentation that survived from the time before Independence, before the 1960s. So I use a lot of family pictures to represent the struggle. To these I add material I’ve generated myself: a photograph I took of mould in a fishtank for example. I also have a microscope at home, so much of the source material stems from different plants I’ve studied under the microscope.

AR In describing the worlds that you imagine through your work – especially swell of spæc(i)es – you’ve referenced Michel Foucault’s idea of heterotopia, spaces that sit beyond society. Given that your project for ArtReview relates specifically to the Power 100, I’m imagining these images act as heterotopic visions of alternative power.

JN Yes, for me it is a way of conjuring a different type of ecosystem, by looking inside other structures of being. I think we can learn a lot from plants, from quantum physics, from all these different disciplines. For example, when researching symbiosis in plants, I thought about how an algae coming into contact with the earth becomes a kind of a lichen, one that can live on earth and take in oxygen, through symbiosis with a mushroom. But this algae used to live on the bottom of the ocean. And you can say that maybe this kind of adaptation through symbiosis is something that human beings can apply to themselves also.

Also in quantum physics and Heisenberg’s theory: the fact that you can’t calculate the speed and the location of a single particle at the same time, because if you calculate the speed, you will lose the position. If you calculate the position, you will lose the speed. You can never fix this single particle, it is always escaping, and I love the idea that it refuses these boundaries of science. That is something too we can take for our own ways of living.

AR But what is it about space and the ocean that specifically attracts you?

JN Actually, I think there are three different types of landscapes in the work. You have outer space, you have the bottom of the ocean, but also you have the cave. All those spaces are renegade landscapes, places in which I can situate all these people who resist against colonial power or a specific form of power, spaces in which they can both hide from that power but also regroup and create their own power. Space is also an important reference within Black culture, specifically coming from [the musician] Sun Ra. As he said at one point, as a Black person, I can’t live on this Earth. I need to go back to Saturn with my people. So this is my spaceship. Now we can start the journey to outer space. And in one way it’s sad – the fact that somehow we have to leave this earth to have a proper life as human beings.

But I also love the fact that he projects not only himself but also an entire diaspora into creating an alternative world where things could be different. It is a manifestation of an alternative reality that can become real. Everything is a kind of weaving of all these references: I read books, a lot of comics, I’m playing videogames, all that stuff, seeing my friends, listening to music, a lot of music. So this is how I work.

AR Tell me about your relationship with Afrofuturism, which relates to the Black(s) to the Future collective, in Paris, of which you were once a member.

JN It is a term I’ve come to avoid slightly, as Afrofuturism has become a kind of label or a contemporary art aesthetic, whereas with Black(s) to the Future we considered Afrofuturism to be a practice of research, a methodology in connecting different dots. It was the foundation of the collective itself that, founded by my friend Mawena Yehouessi, featured artists, musicians, curators and researchers. We did things like workshops, helped stage shows, hosted a festival, but now it’s more a platform for research. We hope to make the archive public soon: projects in which we mapped out the sonic resonance of Afrofuturism from Detroit techno to figures like Ibaaku, a Senegalese musician who became a friend.

AR Were you always into science?

JN This summer I went back to my parents’ house in Paris and found a signed picture of the first Black astronaut [Guion Bluford]. I had asked my parents to go to this tech and science fair on the edge of Paris when I was seven or eight, and he was there. When I found this picture, I thought about how much he must have powered my imagination. Here was the beginning of all this fantasy, but it wasn’t science fiction, in fact, it was something real. A Black astronaut!

AR Did it make you want to go to space?

JN No, I wanted to be a submarine scientist! But that was not the path I took in high school – I don’t think I could be confined by something so specific. I loved the sciences, but music mostly, also literature.

AR Well, you’ve basically made your own exploratory submarine with your work.

JN Yes, I guess I did.

Ntjam has created the artist’s project pages for the 2024 Power 100, which feature throughout the December issue.