“We’re so far beyond authenticity. I don’t know if it can exist in a society where we’re crafting our identities through social media”

When describing Josh Kline, it’s easy to feel like the ardent proponent of a longstanding fandom. The Philadelphia-born, New York-based artist’s decade-and-a-half practice unfolds like a complex narrative set in a very specific universe. This universe, an intensified yet far from inflated depiction of our current conditions, consists of three bodies of mixed-media work, Creative Labor (2009–14), Blue Collars (2014–20) and a cycle of installations that began with a presentation titled Freedom (2014–16) and is now in its fourth ‘chapter’, Climate Change (2019–). Each chapter of Kline lore is composed of numerous standalone pieces, each a microcosm of the artist’s ongoing concerns relating to economic precarity in neoliberal societies, American culture and politics, and the dignity of the contemporary labourer.

In 2023, in front of riot gear-clad Teletubbies, plastic-wrapped office workers, shopping carts full of 3D-printed human limbs and an immersive ‘climate refugee camp’ in Kline’s first US museum survey, Project for a New American Century, at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, I found it difficult to tell whether Kline was being sincere. There were works like Universal Early Retirement (Spots #1 & #2) (2016), an HD video advocating for universal basic income in the style of a political ad, that I initially clocked as satire. What became palpable as I dug deeper into Kline’s oeuvre was an incessant negotiation between urges to dismantle the unsustainable structures around us and pangs of longing to preserve the good parts of who we are as humans. The ‘recycled’ white-collar worker in Productivity Gains (Brandon/Accountant) (2016), lying in a foetal position on the floor, his body stuffed inside a clear plastic bag, was both a debased object and a commemorated subject. As heated wax models of suburban homes gradually dissolved down the drain in Domestic Fragility Meltdown (2019), their gable roofs and meticulously sculpted shingles revealed to me, for the first time, their sad, fleeting beauty.

Ahead of Kline’s solo exhibition Social Media at Lisson Gallery in New York (through 19 October), I spoke to him about the performative aspects of being a contemporary artist, ways for people to empathise with one another in the era of branded personalities and how property values in the city affect the way artists live and work.

A One-Off Gesture

ArtReview You’ve made everything from sculpture and installations to film and video, so naturally I’m curious how you decide what to make next.

Josh Kline There’s a lot of planning ahead. One of my bodies of work is this big cycle of installations, which is broken up into chapters. So far, I’ve made Freedom, Unemployment, Civil War and now Climate Change, which just opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. These are the four dystopian chapters in the cycle. Eventually there will be two more that are radical utopias.

AR The works in Freedom – those Teletubbies resembling police officers – date back to 2015. Did you already know at that time how the works in your subsequent installations, like Climate Change, would look?

JK The general ideas of the installations have all been outlined since 2014, but when I finally make these things, the projects always change. I’ve had a note since the beginning saying that I was going to make a climate refugee camp installation – what became Personal Responsibility, which debuted at the Whitney. But that was just a sentence or a paragraph. Back then, I didn’t know what shape it would take or that there would be tents. I wake up in the middle of the night with ideas, they go in my notes, then I go back to sleep.

AR Are you a fan of the Notes app?

JK I’m hopelessly addicted to it. I feel like I outline like a filmmaker or a novelist. This is why I work out of a little office. I’m not really a studio artist, which is good given the cost of New York real estate. A lot more is happening in writing and in my imagination.

AR Having all these projects, old and new, right at your fingertips must also affect how you think about medium.

JK I do tend to rotate through media. I’ll work intensely with a medium or a set of strategies for years, and then I’ll need to let it lay fallow for a bit and pivot into something else. There’s a certain amount of restlessness in the process.

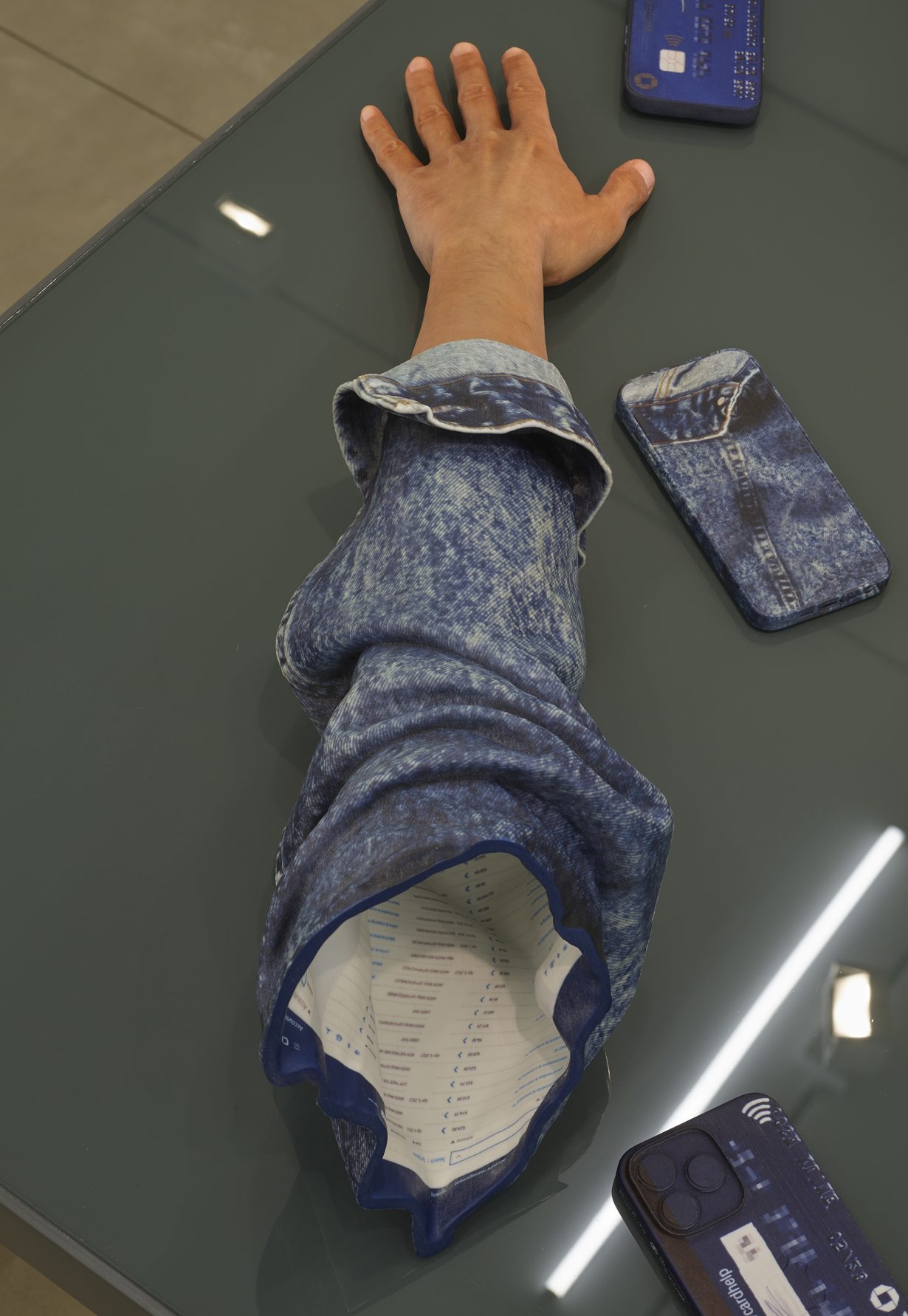

AR Speaking of pivots, your recent gallery exhibition Social Media was billed as your first foray into self-portraiture. Much of it isn’t self-portraiture in the traditional sense. The depictions of you are fragmentary and metonymic. I’m recalling, for instance, 3D-printed sculptures laid out on a table in Professional Default Swaps of just your arms and of computer keyboards, smartphones and other devices you use. But there is also a replica of your entire body in a plastic bag on the gallery floor – a work aptly titled Mid-Career Artist. Is this show indicative of a broader directional shift in your practice?

JK Bringing myself into the work is something I’ve done a bit in the past, but this is definitely a one-off gesture. I’m not going to suddenly start making work about myself. But some of the forms that I’ve used over the past 15 years are coming back in a new configuration, and I’m the vehicle this time. I’ve never done this much self-portraiture before or self-portraiture on its own. It’s always been me with a bunch of other people.

AR Right – for example, in Flattery Bath 2, the ‘spa’ you set up in a hotel on the High Line in Manhattan as part of the MoMA PS1 group show New Pictures of Common Objects. You’re pictured in the video documentation of that performance, but you’re with your collaborators and your ‘spa guests’.

JK I’ve been reticent to put myself in my work after that early experience.

AR Did people recognise you from the video?

JK Yeah, and it was weird. I realised that I prefer to be behind the camera, which is another reason why I think Social Media will be a one-off.

Other People’s Faces

AR You do play with the idea of celebrity in your work, in a way that encourages empathy rather than pure voyeurism. I’m thinking, for instance, of Forever 27, your face replacement video – and proto-deepfake – of Kurt Cobain. His face glitches because it’s been digitally layered on top of that of an actor you cast, and he’s talking about his failed art career. He seems like he’s falling apart in more ways than one.

JK I’m drawn to representation and figuration, and to real places, substances and phenomena. I think representation can be powerful because, as Judith Butler said, we have this innate empathy that gets activated by seeing other people’s faces.

AR ‘To respond to the face,’ Butler wrote in Precarious Life, ‘to understand its meaning, means to be awake to what is precarious in another life or, rather, the precariousness of life itself.’ Curator Therese Möllenhoff quoted this in an essay on your 2020 show at Oslo’s Astrup Fearnley, Antibodies.

JK I think this is why cinema and television are such powerful media, because you see actors – characters – living out these stories, and you either identify with them or you imagine yourself in their place. Through those surrogate experiences, you come to understand something personal to you or something about the world we live in. When I made Blue Collars, the sculptural portraits of working-class people, there was a casting process – in this case, not casting as in mould-making, but casting as in street casting and working with agents – during which I asked myself, ‘Is this person’s story relatable?’

AR It’s funny to think of relatability, which is perceived as this spontaneous connection with another person, as something that’s constructed through long, labour-intensive processes. At the same time, relatability is often associated with ‘authenticity’.

JK We’re so far beyond authenticity. I don’t know if it can exist in a society where we’re crafting our identities through social media, where everyday people are constructing branded personas like movie stars or celebrities that are affecting the way they behave in their private lives.

AR With Social Media, it seems like you’re getting at this idea of presence, particularly the kind we expect from artists. We look for traces of ‘the artist’s hand’, we expect them to be available for openings and talks, and so on. In a sense, your work is performative, but in a way that hopefully starts a conversation about how we perform for social media, as well as for the artworld.

JK It is absolutely a performance in the same way that an actor in a film performs. They’re not onstage every night. They do their work in front of the camera, and the images go and perform them, over and over again. I don’t know if I can be in the gallery with my self-portraits. It might be like being at your movie premiere and standing onstage while people are watching the film. I’m thinking I need to get even bigger sunglasses for the subway.

The Future

AR Another side of social media is the part that makes us feel like we’re always ‘on’ and self-commodifying or at least self-surveilling. I’m reminded of the hands cast in silicone holding iPhones and cameras and arranged like convenience store items on a shelf in your earliest body of work, Creative Labor. That series spoke to the precarity of an artistic career. It’s odd to see how, 15 years ago or going back even further, the erosion of personal and professional boundaries was already something commonplace and accepted.

JK The collapse of the boundary between art and life in the 1960s and 70s gave way to the erasure of the boundaries separating work life, personal life and family life.

AR It seems especially relevant now to think about what effect this kind of precarity in the creative fields is having on art and artists.

JK I’ve been thinking about real estate in New York and cities like it – what it’s doing to contemporary art. Because it’s not good. Most artists, except for the ones who are stupendously wealthy, are working five or six days a week and somehow scraping together cash for a studio. Art is ultimately dependent on real estate. Unless it’s happening online, art requires physical space, and artists need to find a way to either get that space here in New York or break free of this place. It’s still possible to reclaim control of where art is going. Fundamentally, that’s always driven by artists, so artists always have to make that call. If you’re dissatisfied with where something is going, you have to break with it.

AR Speaking of uncertain futures, your 3D-printed sculptures – Productivity Gains (Brandon/ Accountant), Aspirational Foreclosure (Matthew/ Mortgage Loan Officer) and even Mid-Career Artist – besides looking uncanny and synthetic, look particularly durable and archival, especially compared to works like Domestic Fragility Meltdown, which are designed to expire. Are they?

JK Since I first started working with full-colour 3D-printing, the resolution has gone up, and the sculptures have gotten sturdier. I think some of the synthetic quality of the 3D prints comes from limitations of the technology. There’s something that creeps in when the model is generated. A distortion, an error. I have to go through this long process of art directing to try and get the model to look more like the real person. The digital version of the work is also just a higher resolution than the printers are capable of right now, so the sculptures in the gallery look less realistic than the models in the computer.

AR If there were no technological limitations, would you want your sculptures to appear as high-resolution and glitch-free as a person does IRL?

JK It depends. I wouldn’t change those early face replacement videos – the glitches became part of it. Over time, as my sculptures fade in the sun or break and get reprinted, the prints will get better. These works will become more realistic in the future than they are today.

AR I’m curious how future viewers will relate to an even higher-res iteration of Mid-Career Artist. Perhaps the remake will evoke more empathy than its low-res counterpart, and the low-res work will elicit some form of nostalgia for our present moment – a past from which they’ve hopefully distanced themselves.

JK I guess what you’re making me think right now is that, as the sculpture moves into the future, maybe that distancing won’t happen.

I think it has the potential of making the past more real for the people looking at it.