“If I have a certain amount of power and I’m able to create a platform for some young creative people who don’t feel that they have as much power or value, that’s a conversation I’m very interested in”

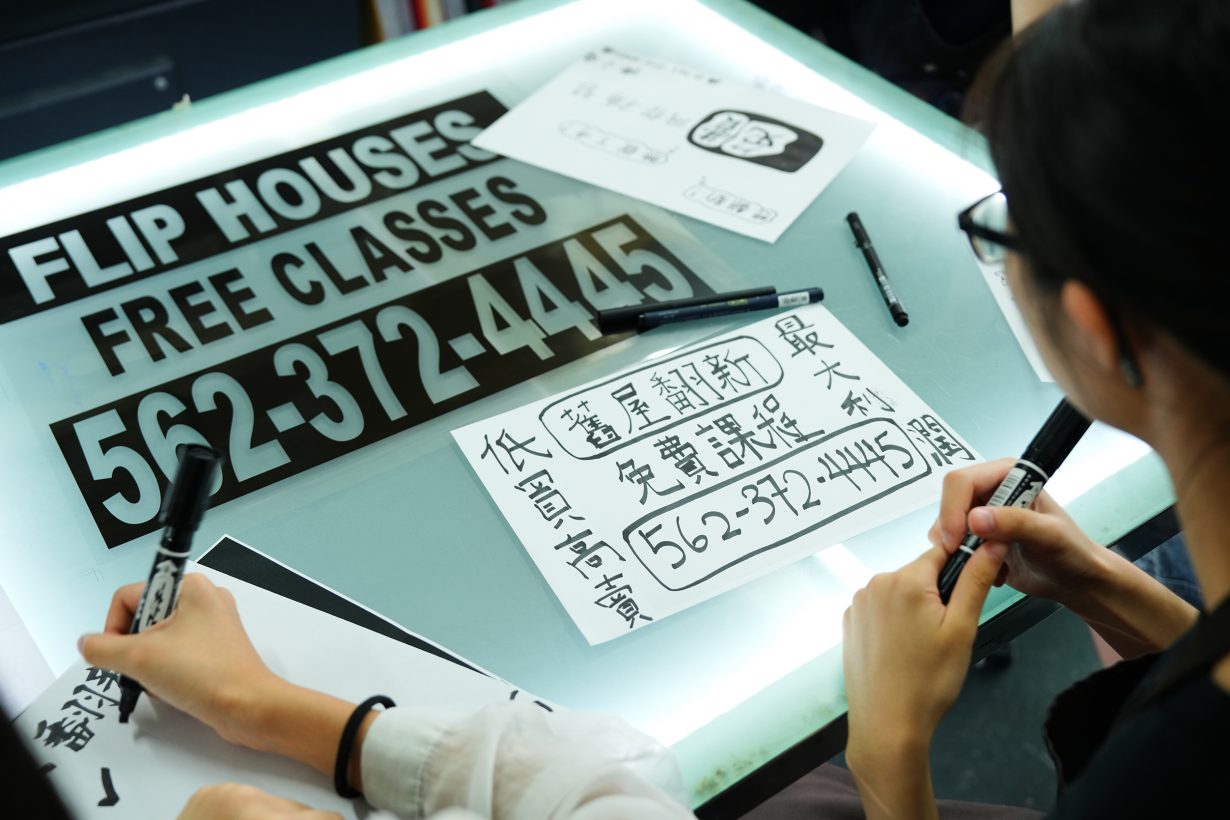

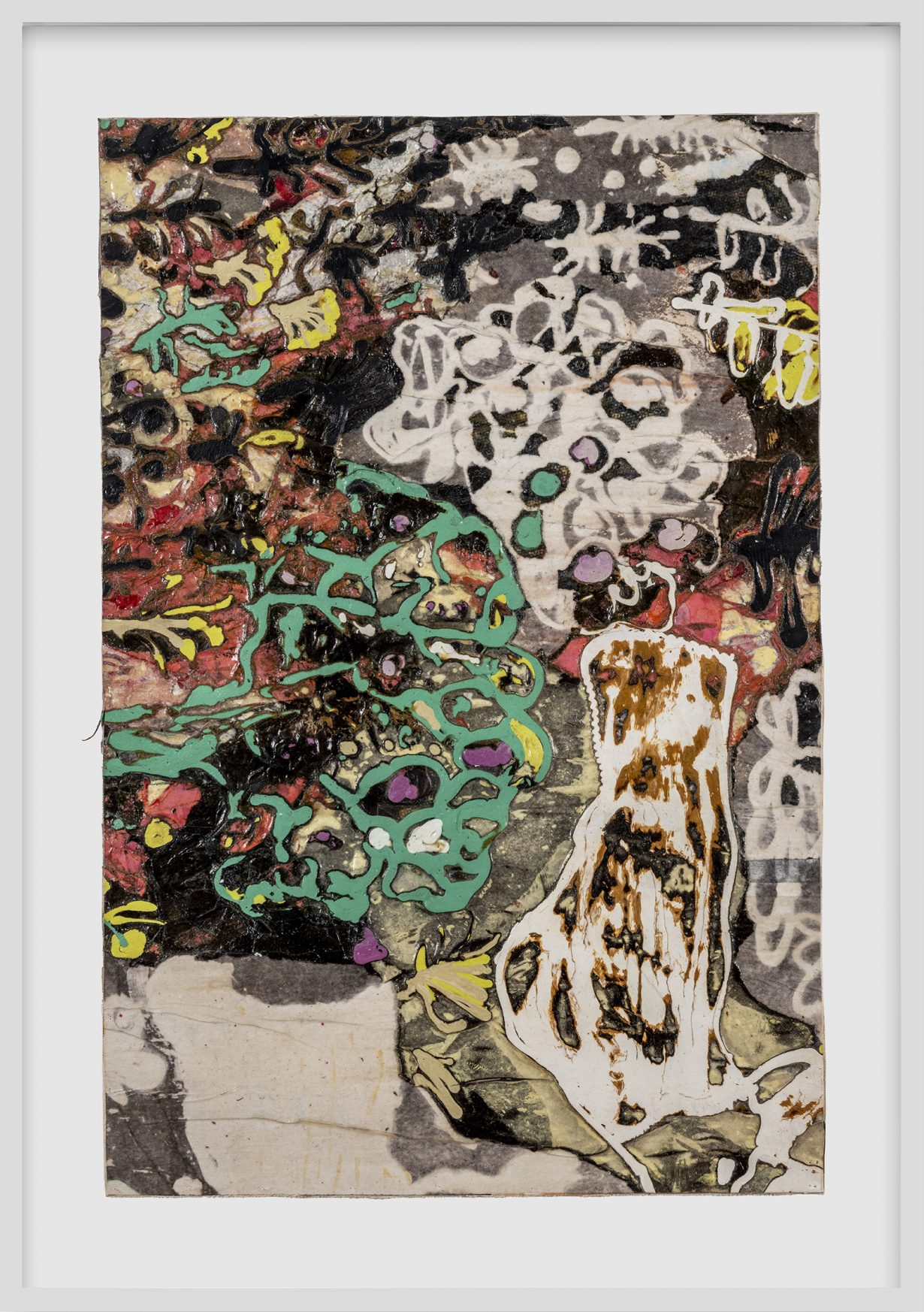

Mark Bradford’s exhibition of paintings Exotica is currently on show at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong, in its gallery at the heart of the city’s financial district. These new, sometimes brightly layered works feature shadowy imprints on the canvas as well as staining and dyeing, and reference the cataloguing of plants that were deemed ‘exotic’ to Western sensibilities during the 1960s. In parallel, since July of this year, Bradford, Hauser & Wirth (via their education department) and the team of Bridge+, a community project centre across the bay in the Sham Shui Po neighbourhood, have been working with young people from the area to create another exhibition. Drawing on Bradford’s Merchant Poster series (2010–), which began with the artist finding inspiration in the informal signs and posters advertising goods and services made in his neighbourhood in Los Angeles, the participants created a mural in Bridge+ as well as displaying their own versions of merchant posters based on local sources.

Such community engagement and outreach have long been a part of Bradford’s practice. In 2013 he cofounded the nonprofit Art + Practice in South Los Angeles to bring art into local neighbourhoods and to explore the ways in which arts education can function to build communities and provide a space in which to address more general social issues. The programme more specifically engages with young people and foster children as well as providing free access to institutional art shows. For the past eight years (starting in the leadup to exhibiting at the US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, in 2017), the artist has also collaborated with the Venetian nonprofit Rio Terà dei Pensieri, which provides work for people currently or recently incarcerated in the Venice area. Previously Bradford has described this aspect of his practice as belonging to his understanding of ‘the artist as a citizen’.

South Central to Central to Sham Shui Po

ArtReview How did the community project at Bridge+ come about?

Mark Bradford Initially, I just came to Hong Kong to look at the gallery’s space, but I did start looking around the city a little bit and I always look at different neighbourhoods. It is always organic. This neighbourhood was interesting and I met the people that ran Bridge+. You could tell that they were really committed. That’s really how it goes for me. You really have to have a tribe. You have to have everybody in agreement philosophically that this is something that we want to do.

AR The Sham Shui Po neighbourhood is different from Central, where the gallery is.

MB Yes, it’s like Beverly Hills and South Central [in Los Angeles]. I’m comfortable in South Central.

AR The project seems like a reversal of the traditional exhibiting tactic, which is that the audience comes to the art; here you’re bringing the art to an audience. Perhaps this is also a reminder that there are some communities that wouldn’t under any circumstance go to a gallery because they don’t feel socially included in gallery spaces; just as much as they might not in high-end fashion stores.

MB That’s what I’m trying to break down a little bit. I’m not trying to hide that I’m having a show at Hauser & Wirth in Central, which is a very different thing. You have to acknowledge that power isn’t equal when you move into different spaces. If you make the assumption that we start from equal footing, you’ve lost. It’s not equal. Asking young people to come out of their neighbourhoods and come into Central and art museums, while also asking them to ‘be yourself, be comfortable’, is asking too much, because they just can’t.

AR What are you hoping the project achieves?

MB I always want to create a safe space where conversations can go on between young creative people, just to create a conversation between me and them and the conversations between each other. Some of it takes root, some of it’s just a one-off. Some have no interest in going to art school; sometimes there are other chapters.

The young people taking part, they always start very, very quiet and they don’t really own the project. By the end, they’re bringing their parents and their teachers in. I love to see young creative people having the possibility of taking centre stage, owning their voice and owning their possibility and expanding their possibilities.

Sometimes the parents will come and I’ll say, “Your daughter was just brilliant in this whole process.” You’ll see the parents sometimes begin to change and listen in a different way. “Really?” I believe in us; I believe in young creators. It’s funny, no matter where I am in the world, there’s always a commonality, a shyness, where creatives seem to fit in with some parts of the family and not sometimes with the other.

Time Travel and Other Powers

AR Are your expanded projects about giving people a sense of agency in situations where they don’t have it?

MB I didn’t have a lot of agency growing up. Agency and connection and access and power, I think all these conversations should be more transparent. If I have a certain amount of power and I’m able to create a platform for some young creative people who don’t feel that they have as much power or value, that’s a conversation I’m very interested in.

What I’m really fascinated with is young people before university. What happens to those young creators from that 9th grade to that 12th grade who are trying to figure it out? Maybe they don’t have the grades to go to university. That was my story.I want them to know that they have value.

AR Do you have a feeling of guilt about the things you have achieved with your life? A psychologist might attribute that to your desire to help others…

MB I don’t feel any guilt. I feel in some ways these young creative people are my community. It reminds me of when I was a kid. To have a conversation with a creative community, it’s almost like time travel. It feeds a certain part of me. Not guilt, no. I find it empowering.

AR When you are approaching these social spaces, sometimes as an outsider, how do you negotiate the ‘permissions’ you need to be a part of them? And do you know what people taking part might want?

MB I spend a lot of time just listening and almost never talking about what we’re going to do, almost to the point where they say, “Are we going to do something?” Just because it’s really, really important, because I don’t want to make them more uncomfortable than, quite frankly, they already are.

I think one difference for me is that I never taught. I never worked inside the university system. I had developed all these strategies for learning how to pay your rent and learning how to do all of these things. It was easier for me to tell young artists these are the strategies that I’ve developed because I know that I’m 100 percent responsible and there’s no cheque coming in the mail. There’s no anything coming in the mail. When I started the educational projects, it was like, “Nobody’s coming, we have to figure this out. It’s all us. We just got to figure it out. We got to make this happen. We got to build.” That DIY thing I think was something that helped me quite a bit.

I never make any assumptions. If it’s not safe, somebody’s got to pay for them to get there. Are they hungry? You have to feed them. What support system is going to allow them to be part of this? Is it their teacher? Is it their mother? You have to ask, because oftentimes they’ll just hide it from you because they’re like, “I want to please you, or I just don’t really want to tell you what I’m going through or how difficult it is.” I know that feeling of hiding parts of yourself to be accepted.

Calling All Artists

AR In some ways you’re operating in a private space, but what you are tackling are public, societal issues for which governments and state infrastructures should have responsibility. Do you think you’re plugging gaps in what society should be providing, or do you think you can act to change broader ways of thinking? Given that the art world remains stacked against people from lower-class backgrounds.

MB If you’re an immigrant or from a lower-class background, if you do go to university and you do have good grades, you’re probably going to go towards something to ‘make money’. Then the second generation maybe or the third generation can be the artist. I don’t believe that. I think that some of the migrant stories are so incredible just now, my God, some of the urgencies and the things that I have. These are the stories of the twenty-first century that should be in the artworld right now.

More people should be at the table. They should come from more diverse backgrounds and economic backgrounds and class backgrounds and whichever how-you-got-here backgrounds. It should be. It shouldn’t be everyone entering in is coming from a good middle-class family. Then you’re able to go to art school, then you’re able to make your work. No, I think it should be more varied.

AR Have you found your interests and experiences in Los Angeles can apply in Hong Kong? Are these general, or even universal issues?

MB When I got here and we started working, it turns out that housing is a big conversation in Hong Kong. On every single little piece of area, you had these little merchant posters, these little things stuck everywhere, like Los Angeles. That was just a coincidence, really. But the coincidence did start a conversation about housing and migration and urban spaces and memory. With the Merchant Posters and the students, they kept saying, “Oh, it feels like Hong Kong local.” I said, “Oh, no, all of these spaces, all of these posters came from Los Angeles.” There was a way into a conversation that wasn’t didactic or wasn’t obvious. It came through this idea of public space and housing. I started collecting all the housing posters, and then they translated them and they did a silkscreen project. Silkscreen was the first thing I learned. It has a very physical quality to it and I really liked that.

I was very happy about that, when they start to own the project and you’re really just there to work and move in and out of it, zoom in, zoom out, micro, macro. The conversations just come out of that.

AR While you help create space for younger creatives, is there a point that you could identify in your career when you felt accepted, that you felt you belonged within the art system?

MB I don’t think I was going to ever. I don’t even think I think about that. By that time, parts of your community don’t accept you and part of your family doesn’t accept you, your race, people are telling you they don’t really like it. I’m so over that. I’m just like, OK, the line goes to the left. I know that it’s naive to say, “Oh, I’m exactly the same person as 25 years ago.” No, I’m constantly rethinking how to move my career forward.

What are the things that mean what are important to me? What are the traps? Why am I doing certain things and not doing certain things? I ask myself those questions because when you do this type of work, one of the things is time. If I’m going to do it, I had to come here and work. It’s not like I drop in and have a show and a dinner and go. No, the time. You have to give time. If you say something has value but you’re giving it no time, people can see. People aren’t stupid. People have eyes.

AR Do these social projects and conversations inform your work as an artist? In an age when a lot of art is involved in a capitalist circulation of one form or another, the social projects are a way of rerouting some things. Do you separate your gallery work and social work at all?

MB At this age, I think it’s just all me. I don’t think I even spend any time trying to dissect myself anymore. I am what I am. These type of projects root me in a different way. That’s just not a conversation about just the gallery and me, ‘Mark Bradford’ with the big M and B. I don’t always like the isolation of everybody working for me, everything me. This grounds me in a much more of a collective way.

Mark Bradford’s exhibition Exotica is on view at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong through 1 March. Work made by students in Bradford’s Merchant Posters education lab can be seen at Bridge+, Hong Kong, through 20 October

From the Winter 2024 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.