Golden opened the floodgates for a generation of Black artists to just be themselves. Now, ahead of the Studio Museum’s reopening, the director speaks about shouldering the weight

Before Thelma Golden became the Studio Museum in Harlem’s director and chief curator, she organised the 1993 Whitney Biennial, a politically conscious and ethnically diverse exhibition that was unafraid to, as The New York Times put it, ‘stick its neck out’. Works included metal admission pins that read, ‘I can’t imagine ever wanting to be white’ (by Daniel J Martinez). A year later, Golden was back with the 1994–95 group exhibition Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art, which provoked the ire of yet more critics but moved the needle on the discourse of Black postmodernism.

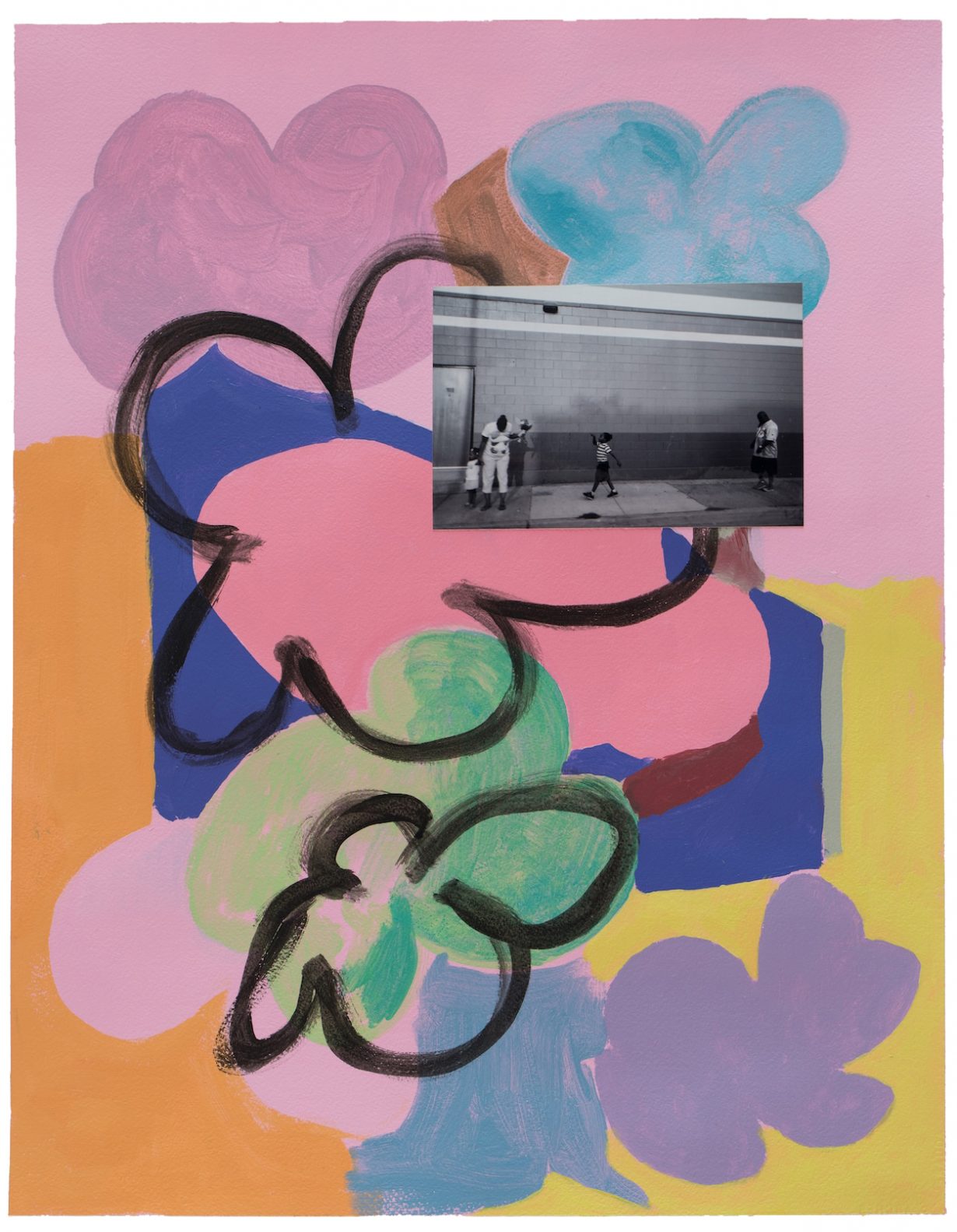

Half a decade later, having joined the Studio Museum in its J. Max Bond Jr-designed building – a retrofitted bank located at 144 West 125th Street – Golden curated a group show titled Freestyle (2001), which included 28 early-career Black artists, including Mark Bradford and Rashid Johnson, who embodied what she termed a ‘post-Black’ sensibility: they sought to do something with their work other than represent Black culture – in short, to redefine the very notion of Blackness.

While her curatorial approach opened the floodgates for a generation of Black artists to just be themselves, Golden, for her part, has been happily shouldering the weight of an esteemed, longstanding and fundamentally mission-driven art institution for 25 years and counting. Helming the Studio Museum as it enters a new era in an Adjaye Associates-designed edifice – built, following a $300 million capital campaign, where the humble bank once stood – Golden is poised to steer its legacy through the tumult presently facing arts institutions across the US.

ArtReview The artist Tom Lloyd, who was the first resident selected for the Studio Museum’s influential Studio Program, will be the subject of one of the first exhibitions in the new building. Back in the 1960s, amid the civil rights movement and the Black Power movement, Lloyd was making large, abstract aluminium sculptures using multicoloured lightbulbs. This was a time when Black artists were expected to make figurative art. In what ways does returning to Lloyd’s work in this moment feel meaningful to you?

Thelma Golden Tom Lloyd lived so significantly in the story of the Studio Museum in Harlem, because when we were founded in 1968 – and we opened in September of 1968, at 2033 Fifth Avenue, which was the museum’s original space – the inaugural Studio Museum exhibition [Electronic Refractions II, 1968] was a survey of Lloyd’s work. At that moment, this was an incredibly exciting and innovative possibility. Lloyd was an artist working with light, working with technology. He was someone invested in the experimentation of that era.

The Studio Museum is an institution that at its founding had committed itself not only to steward the history of Black artists but also to work deeply in the present, supporting the work of Black artists. Lloyd was, at that time, opening new forms and thinking about new forms. Although his work has been included in several important exhibitions – Energy/Experimentation: Black Artists and Abstraction 1964–1980 [2006] at the Studio Museum, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power [2017] at the Tate – his work has not been seen enough, since the time of that inaugural exhibition. To actually claim fully his legacy and be able to show all that he did is important to us as a way to open the building and open this new chapter of the Studio Museum.

AR How have the priorities and responsibilities of the museum evolved since its founding?

TG I often say that our founders gave us the gift of clarity of mission in our name. The ‘studio’ in our name comes from the fact that, since the founding of the museum, we have had an artist residency programme, where every year we’ve hosted three artists who have received a financial stipend and 24-hour access to a studio in the museum building. Also in our name is ‘museum’. In the late 60s, in many places, and in many ways, there was a thought about redefinition of museums: what they should be, where they should be, what physical shape they could take. This is the moment where we begin to get what we understand to be the alternatives to a historic museum structure. So by naming the Studio Museum ‘museum’, our founders were claiming that word, but with the idea of the museum being in their hands, as something that they wanted to redefine. And then, of course, the ‘Harlem’ in our name was about siting us in Harlem, geographically but also intellectually and spiritually. The Studio Museum’s priorities and mission were made manifest, in those words. That has only continued to deepen over the years.

AR It’s funny that you mention a push to redefine the role of the museum in the 60s, since many of us today are also questioning the ways museums function – socially, politically, locally and globally. A lot has changed in the US since the Studio Museum went under construction eight years ago, but I wonder if a lot of what’s happening today in museums – and to museums – may be less unprecedented than it feels.

TG The museum being closed for eight years has given me a chance to invest deeply in our past and our history, and what we understand are the cycles of history. Our founders, our inaugural director [Charles E. Inniss], the curators and educators were working in [19]68 in a moment that is very much like the one we’re in now. Museums remain important civic institutions for the discourse of ideas. They are a critical part of our larger civic dialogue.

AR Thinking about how the physical architecture of museums are often used to signal power, and the layout of galleries inside a museum is often hierarchically designed, can you speak a bit about the floorplan of the new building? How are the various floors organised, and how will they be utilised?

TG This design of the building was really meant to serve our ambitions and aspirations as an institution. All of the galleries are designed to accommodate all of our exhibition programmes. The gallery spaces sometimes will have our collection, sometimes will present changing exhibitions; most often there will be a combination of the two. There are ways the galleries could be combined to encompass one exhibition throughout the building. For the opening we will have a presentation of our collection, and it will be installed in that way to allow for intergenerational, cross-media dialogues that will allow visitors to see the depth and the breadth of the museum’s collection. Our institution has from its founding been deeply invested in having exhibition-making and our collection be part of a larger dialogue about opening the canon and showing, in complex and nuanced ways, the contributions of artists of African descent through the centuries.

AR How does it feel now that the museum is finally reopening?

TG We’ve been closed – not planned – for a long time. When we started this project, we imagined a shorter period of closure and opening, and the many things in the world that happened have made this a longer process. While we were closed, we did not stop programming, because we had an incredible partnership with the Museum of Modern Art, which allowed us to continue to work with artists in our artists-in-residence programme, and then create a new series of exhibitions for MoMA’s Project Space. And so our first was in 2019, when they reopened their expansion, and that was Michael Armitage. Then we were able to present the works of Kahlil Robert Irving, Garrett Bradley, Ming Smith and Tadáskía over these intervening years. Those programmes allowed us to continue to be in the world, making exhibitions.

AR Many people pictured you as the next MoMA director. Was this something you considered?

TG This is my 25th year at the Studio Museum. I began my career as an intern at the Studio Museum. I have been associated with the Studio Museum since I was nineteen years old, and it’s a museum that has inspired me, educated me and changed me in profound ways. My commitment is and has been to this institution, but I’ve been privileged to have the opportunity to work with other institutions. I am on the board of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, and that has given me an opportunity to understand other kinds of museums. I am on the board of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, so through that I get the chance to experience the incredible work of all kinds of arts institutions around this country. I feel like the question of what I will do next isn’t really the question, because what I will do next is what I am doing right now. My work has always been defined by the present.

AR What do you think is the biggest challenge for museums today?

TG To create experiences that allow many different audiences to engage with our institutions. As someone who’s grown up in museums, I have only ever worked in museums, and my desire to work in museums began when I was a very young person, a high school student here in New York City. I have watched the ways in which museums have transformed to speak to many different groups of people in many ways. The polyvocalness of institutions is what makes it possible for museums to continually evolve.

AR Do you sense any burgeoning trends or sensibilities among emerging artists today, anything comparable to the tidal shift you articulated when you coined the term ‘post-Black’?

TG I don’t know if I could define any trends or sensibilities. What I am seeing, what I continue to see, is artists providing us with an important opportunity to see and think through their work. And I feel like, in the world we’re living in, it is an incredible gift to have the opportunity to be able to imagine a future. And that’s what art can and does often allow us: the space where we can bring the questions that define how we understand ourselves, the world and each other into a context that gives us a sense of real possibility and, I might even say, power.

The Studio Museum in Harlem reopens on 15 November

From the October 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next Mark Bradford in conversation with Mark Rappolt: “If I have a certain amount of power and I’m able to create a platform for some young creative people who don’t feel that they have as much power or value, that’s a conversation I’m very interested in”