What do we lose when gay bars make way for queer museums?

Attending Pride London always seems like a nice idea, until the reality kicks in: the once radical march has largely been reduced to a theatre of rainbow-branded goods and storefronts that hardly inspire any pride at all (M&S LGBT sandwich, anyone?). This year, however, was going to be different. After two years of cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and to mark the event’s 50th anniversary, the capital welcomed two new queer art spaces. So, after claiming my complimentary canned rosé at a Scandinavian concept store in Soho, I began my cultural expedition and, polyester rainbow flag in hand, marched down to Queer Britain, ‘the UK’s first national LGBTQ+ museum’, in King’s Cross.

Inside the Art Fund-owned 1850s brick-building, on Granary Square, an introductory exhibition titled Welcome to Queer Britain spans two rooms of photography and archival material from the museum’s collection. One display, taken from a 2019 exhibition of the same name, is titled ‘Chosen Families’, referring to queer kinship networks (formerly indicted as ‘pretended family relationships’ under the Thatcher government’s Section 28). It features editorial-like portraits by UK-based photographers Alia Romagnoli, Kuba Ryniewicz, Bex Day and Queer Britain trustee Robert Taylor, which, all together, appear

as an uncritically choreographed parade of bodies. A blurb on the wall explains that they were co-commissioned by the institution’s partner, denim brand Levi’s, to celebrate ‘the diverse, imaginative and deep relationships which sustain, challenge and nourish us’. While the nature of said commissioning isn’t detailed, the implied curatorial involvement of the fashion giant troubles the display’s ambition. Put simply: whose ‘deep relationships’ are we truly looking at?

In the next room, another display, titled ‘Capturing the Rainbow’, consists of a puzzling selection of archival photography from the 1870s to the present day. It includes images of male impersonators in Victorian England, crossdressing First World War British soldiers and Princess Diana visiting the aids ward of a Brazilian hospital in 1991. According to the wall text, they were donated by Getty Images and Queer Britain’s partner, the advertising empire M&C Saatchi, which, need I remind you, was built on the back of Tory campaigns: starting with the 1978 ‘Labour Isn’t Working’ billboards credited with bringing Margaret Thatcher to power and, a decade later – the year before Section 28 was enacted – the ‘Is This Labour’s Idea of a Comprehensive Education?’ poster displaying three ‘disgraceful’ books, one of which is titled Young, Gay & Proud (1980). As I exit the museum, I’m left with the impression that I know more about its portfolio of corporate sponsors than its curatorial vision; but also that the former dangerously informs the latter.

A few days later I travel south of the river, where Queercircle graces the former industrial area of Greenwich Peninsula, now home to the hip Design District – brainchild of Hong Kong mega-developer Knight Dragon. This space, however, is not a museum – it doesn’t currently have a collection. Instead, Queercircle is ‘a new home for LGBTQ+ arts, culture and social change’ – at least that is what a large poster announces on the facade of its freshly opened gallery, housed in a David Kohn-designed building. (The organisation, which has been active since 2016, has secured a five-year lease with the support of the Greater London Authority, the Outset Contemporary Art Fund’s Studiomakers Initiative and private donations.) Yet as I look around the surrounding swanky office blocks, I wonder what kind of social change can be achieved here, aside perhaps from boosting the locale’s ‘Gay Index’ – the magic ingredient to any successful regeneration scheme, according to place-making guru Richard Florida. (Read: ‘bring the queers and your otherwise dull development will prosper’.)

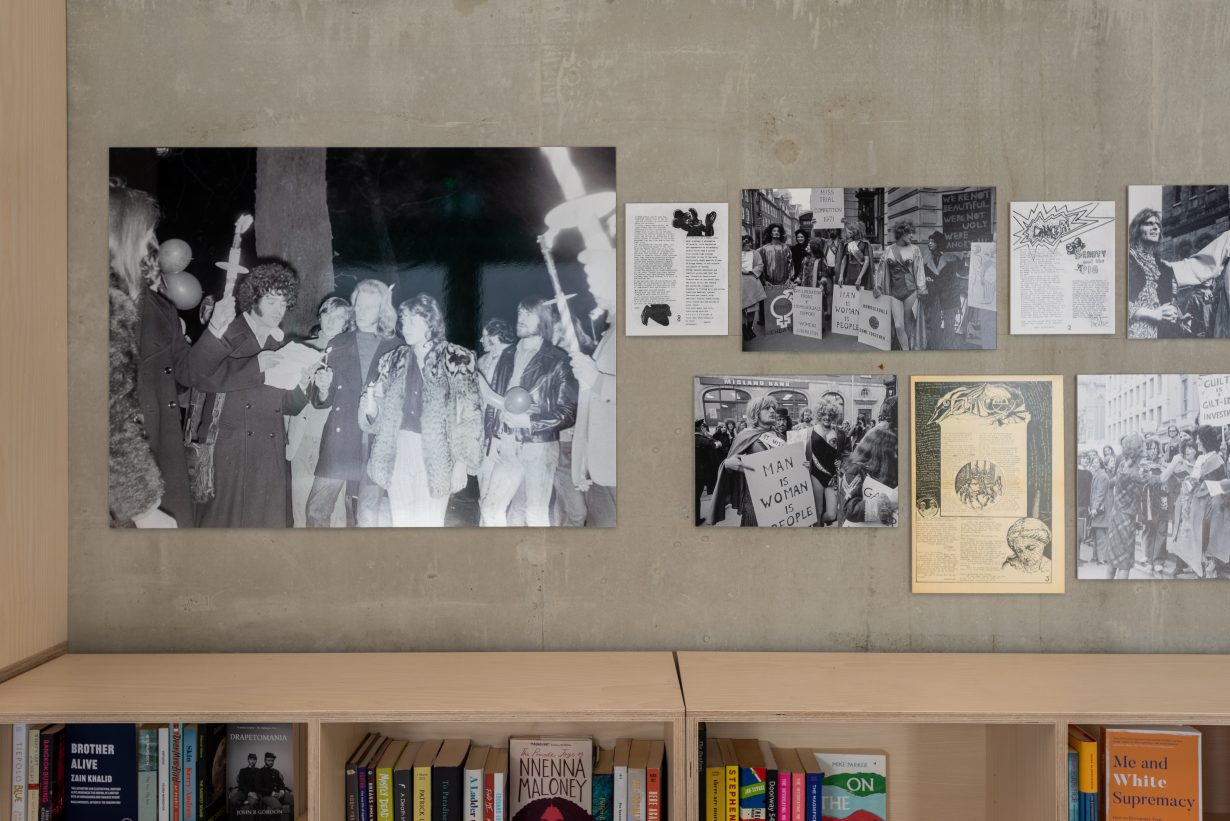

As at Queer Britain, entry is free. Good. Inside, two inaugural exhibitions prove delightfully compelling. Alongside a new installation by London-based artist Michaela Yearwood-Dan in the main space, the fabulously titled display The Queens’ Jubilee! is exhibited in the venue’s modestly furnished library. Co-curated with artist and gay campaigner Stuart Feather, it features a selection of archival material – spanning photography, articles and poetry dating from the 1970s – drawn from editions of the Gay Liberation Front’s newspaper, Come Together. One photograph shows half a dozen wigged and costumed GLF members performing outside Bow Street Magistrates’ Court in solidarity with the incriminated feminists who had stormed the Miss World contest a few months prior. The material insightfully – and entertainingly – documents the introduction of drag street theatre into queer politics in the UK, nodding to the radical potential of performance in the public realm.

In the pink-pound era, however, I question whether queer liberation is best served by institutional models. Or rather I question whether the ‘museumification’ of queerness is at all cause for celebration. (Call me nostalgic, but I would trade any museum for one of the many stale-smelling bars that have been priced out of London in recent years, particularly if they come with a cubicle-turned-gallery, as did the East End pub George & Dragon, and now the Queen of Adelaide.) Instead, ‘the will to institutionality’ – as queer and critical-race-theory scholar Roderick Ferguson aptly puts it – should be scrutinised, for its promise of legitimacy often comes at the cost of normalisation. If London’s new queer institutions are meaningfully to serve their communities, they should not only welcome institutional critique, but actively encourage it.