As a recent publication details the impacts of Islamophobia in India, Deepa Bhasthi asks if it’s already too late

By the time this column (written in early August) is printed (in October), one can be certain that the litany of mob lynchings, rapes, murders, hate speeches and open calls to ‘free’ India of Muslims will have grown longer. General elections are less than a year away, and nothing appeases the proliferating Hindutva militancy – whether it dons the garb of the politician or the foot soldier on the street or the trolls on social media – as much as horrific violence against Muslims. Daily, relentlessly, they remind us that Hindus, Hindu culture and Hindu women are in grave danger of being overtaken in number by the Muslim hordes, of being erased and/or Islamised, or trapped by a ‘Love Jihad’ perpetrated by predatory Islamic Romeos (who supposedly use love as a hook to capture and convert innocent but love-hungry Hindu women). Note, though, that about 80 percent of Indians identify as belonging to one or the other caste or category that falls under the broad umbrella of Hinduism, while Muslims, the largest minority community, account for about 15 percent of the population.

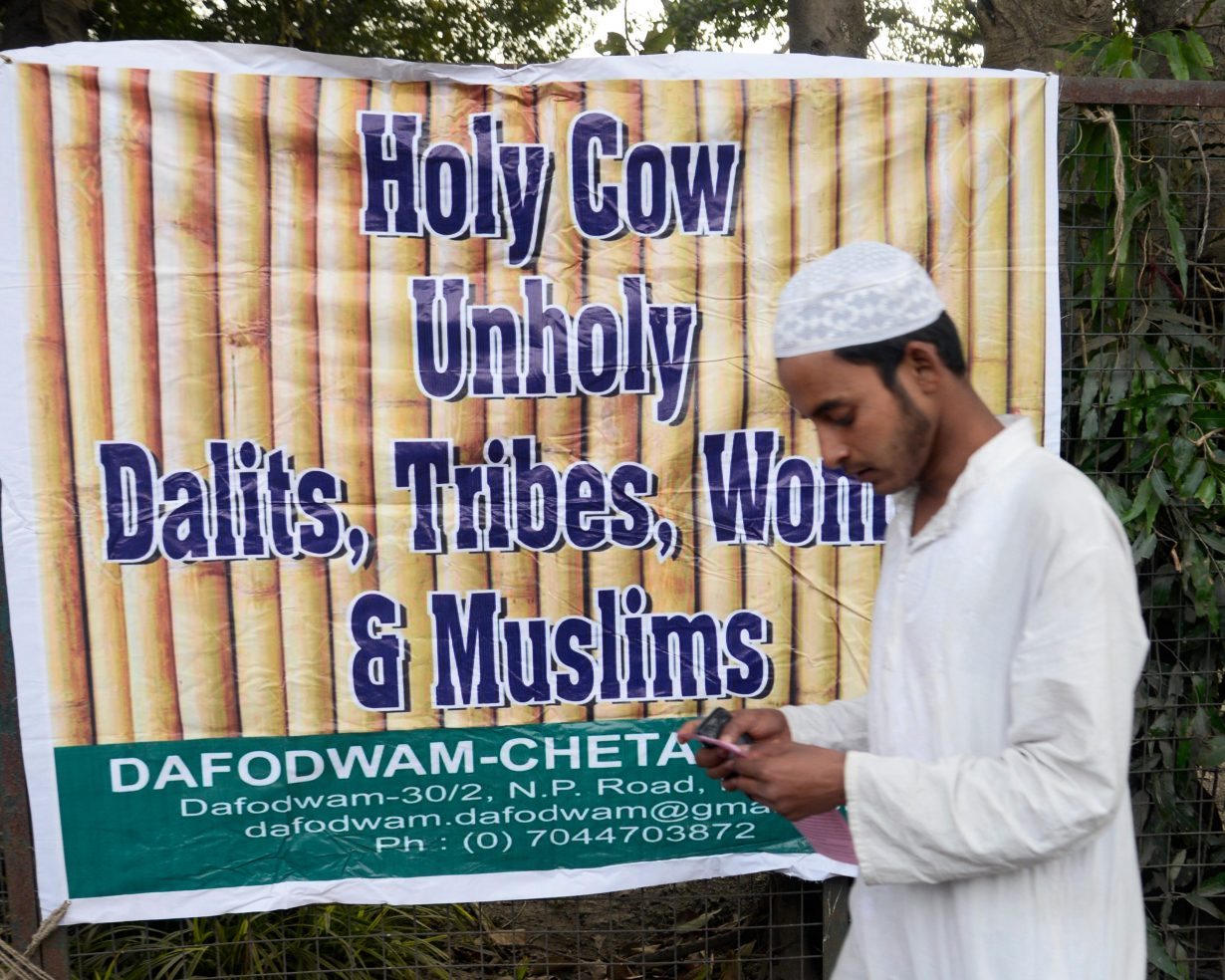

Dalits (formerly the ‘untouchables’, the lowest of the low on the caste ladder), the queer community, tribal and other sexual and religious minorities have never been spared institutionalised othering in India. But this present cycle of hate and violence – which is state-sponsored via policy changes, law amendments and memoricide – targets Indian Muslims in particular. Genocide Watch, calling Islamophobia a ‘state-manufactured ideology’ under the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) – the Hindu nationalist party led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi – declared the country’s genocide ‘alert status’ to be an ‘emergency’ earlier this year. According to the human rights organisation’s country report, the BJP ‘threatens India’s secularist constitution and its future as a democratic nation. Modi’s Hindu nationalist “Hindutva” agenda promotes intolerance counter to India’s pluralistic traditions.’ It goes on to list recent ideology-driven policies and practices, including the discriminatory Citizenship Amendment Act 2019, anticonversion laws, open calls for genocide of Muslims and the horrific case of the early release of 11 men (notably all upper caste) sentenced to life in prison for gang rape and murder during the 2002 Gujarat riots. The constant stress of this impending danger of being persecuted just because of their religious beliefs, which has been built into a ‘crisis of belonging’, as architect, activist and writer Sara Ather terms it, has taken a severe toll on the mental health of Muslims.

Bebaak Collective, an informal association of grassroot activists advocating primarily for Muslim women’s rights, recently released a report on the mental health of Indian Muslims, researched over six months in six states including Uttar Pradesh and Delhi. Steering away from following strict clinical parameters (often borrowed from Western psychology practices) to determine the extent of fear, depression, anxiety, anger and PTSD that Muslims face in a postviolence context, the study looks instead at lived experience and the changes Muslims have been forced to make in terms of how they live, what they wear and eat, etc. It recognises that there is no ‘post’ in a PTSD case when, too often, survivors of communal violence have to live in locations of chronic political conflict and continue to be exposed to traumas that are repetitive and ongoing. It must be noted that inaccessibility to any kind of postviolence relief is not restricted to India, or to Muslims. Continual trauma arising from persecution is seen in Palestinians, the Tamils in post-civil war Sri Lanka and several other oppressed groups across the world, extending to lived experience even after they are displaced.

The architecture of targeted violence against Muslims, the Bebaak study reports, ‘creates an environment where Muslims are victimised through economic boycotts, vigilante violence, destruction of property, unfair arrests, and imprisonment’. Hate speeches in India by right-wing politicians call upon non-Muslims to avoid doing business with Muslims, economically alienating them. Among the most vicious of othering in recent times has been the demolition of homes and businesses of Muslims, mostly on whimsical grounds, in Uttar Pradesh, a state led by a Hindu monk. In another travesty of justice, the activist Umar Khalid has been in jail for over 1,000 days on trumped-up charges, while those openly calling for genocide get away with barely a rap on the wrist, if that.

The fear that begins to define everyday life for the persecuted community leads, often, to radicalism and in turn retaliation against the majority, spiralling into a systemised cycle of trauma that becomes harder and harder to break. This is hardly restricted to India, though. What is especially chilling is the concurrent rise of religious extremism across the larger South Asian region, home to some two billion people, where institutionalised violence against minorities is ‘often a function of politics’, as detailed in the book Politics of Hate: Religious Majoritarianism in South Asia (2023), edited by the scholar and activist Farahnaz Ispahani. The essays, written by academics, journalists, political analysts and researchers, examine how extremism in the region almost follows a template in the way minorities are persecuted, creating a cyclical crisis of violence.

India is the giant, both in terms of geographical expanse and population numbers. Other countries in the region – Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and smaller nations like Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives – share complicated histories and many cultural similarities. The diplomatic relationship between each country is often complicated, though perhaps none as contentious as that between India and Pakistan. Interestingly, the essays in Politics of Hate analyse majoritarian extremism, its causes and impact only in the larger four nations above. Ispahani reasons this choice by saying that Pakistan, founded on the basis of religion, has long suppressed its religious minorities, while India, founded on secular nationalism, has been sliding towards religious nationalism in the last few years. She goes on to point out that communal majoritarianism has been on the increase in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka as well. The decision to include case studies from just these four nations was perhaps driven by the size of their population, because it is not as if the smaller countries in the region have been spared extremism, however underreported they may be in comparison to their bigger neighbours.

The case studies included several focus points: how mainstream media, almost all of it owned by business empires in India, has been fuelling the fire of Hindutva militancy and manufacturing hate in exchange for profit; Islamophobia in predominantly Sinhalese-Buddhist Sri Lanka, with the precarious situation of Tamils thrown into the mix; the alienation of Pakistan’s many minority communities within the increasingly hardline Islamic nation; and the move towards a more radical form of Islam in Bangladesh, a country that is constitutionally secular. Reading the book alongside the Bebaak Collective report illustrates the long-term effects of religious extremism. The report uses ‘social suffering’ as its main parameter for measuring social hatred and state persecution faced by Indian Muslims, defining the term as an ‘assemblage of human problems that have their origins and consequences in the devastating injuries that social force can inflict on human experience’. The interviewees in the study share stories about the sudden change in familial dynamics in post-violence situations; after, for example, a family member is arrested or killed and justice is sought via a legal system that for Muslims is reduced ‘from a concrete means of ensuring their dignity and rights to a mere “spectacle”’, where complaints may be ignored or not investigated impartially, and pending cases prematurely closed due to political pressure. Economic disempowerment and social division follows, along with the threat of sexual violence for women where rape, molestation and assault are used to control and shame a community. This intersects with more general patriarchal attempts ‘to limit women’s mobility and participation within the public sphere’. The report notes forced changes to Muslims’ everyday lives and interactions with other communities – from not dressing in traditional attire and not being ‘visibly Muslim’, to eating beef (cows are considered holy by Hindus and their slaughter is banned in several states, even though several non-Muslim communities also eat beef), to the kind of education they have access to, which in turn determines the kind of careers open to them – breed further mistrust and a sense of betrayal.

Nationalist governments, like the BJP in India, cultivate this crisis of belonging and helplessness, worsening the alienation and othering of Muslims by hyping up a narrative of Hindus being in danger, using social media extensively to spread such fake news. In India, this religion-based divide-and-rule policy has been especially useful for the BJP to avoid addressing issues of inflation, rising unemployment and corruption charges. The writers and political scientists contributing to Politics of Hate and the Bebaak report suggest various resistance tactics to counter the politics of intolerance, even as they recognise that in most cases the rot has sunk in so deeply that any evolution towards syncretism has to now be a long-term, polity-driven process. Breaking the cycle could well be an intergenerational process of reckoning before there is any reconciliation.