From nineteenth-century opera singers to Rihanna’s sheer Swarovski dress, a new exhibition tells us that we never really knew the women we call divas

Diva, a new exhibition at the V&A in London, is divided into ‘Acts’ and ‘Scenes’. When you enter the costume gallery, you move about in the dark space dimly lit by the screens and lights behind the glass vitrines. Act I storyboards the historical development of the diva, arguing that while its etymological origins can be traced back to the sixteenth century and relate to the notion of the divine, the contemporary idea of the diva takes shape in the nineteenth century: a title bestowed on the most exceptional female performers by audiences who have revered them as distinct.

Through a headset soundtracking the various stages of the exhibition, your ears first encounter ‘Casta Diva’, an aria from Vincenzo Bellini’s opera Norma (1831) in Maria Callas’s 1954 rendition. Nineteenth-century European opera singers are introduced as an origin story for the idea of the diva. A portrait of Spanish-Italian soprano Adelina Patti is accompanied by a breastplate and shoes she’d worn on stage. That presentation of divas through costumes is consistent across the exhibition – there’s the costuming in the section dedicated to ‘Victorian Drama Queens’, with the corsets, velvet brocades and gilded beads actresses like Ellen Terry wore for Shakespearean productions, and the peach silk evening gown worn by Carole Lombard in Hollywood golden age musical We’re Not Dressing (1934).

Moving through Act I, the narrative established around the diva is one of the increased cultural and political power of the female performer, then the consequences thereof. Terry is not only her costumes and her singing voice, but also her offstage involvement in the Actresses’ Franchise League. The era of the Hollywood Diva is also where tensions around the ascendancy of autonomous women in the film industry and their popularity with audiences reached a fever pitch. The rapidly expanding Hollywood studios seized on the adulation for the diva by bringing their image under their express control, offering up insights into the performers’ private lives and leaning into the most obscene and salacious tabloid and showbiz gossip, a move which marked the transition of entertainers into the modern celebrities that we know. While copies of such gossip magazines do not make the show – a sensitive decision but arguably an oversight – this is best represented by a framed page from actress Vivien Leigh’s scrapbook, which features clippings of positive stories about her craft, unsettled during her lifetime by consistent targeting of her reputation for ‘difficult’ behaviour, actual manifestations of her bipolar disorder and depression.

These power struggles have become a defining characteristic of the idea of the diva, and how it shifted from those connotations of otherworldly performance to that of being demanding, difficult and messy. The exhibition does well to surface industry exploitations and dynamics which meant that the career of a diva could be destroyed as easily as it was made by studio executives. The red dress worn by Judy Garland in the 1949 musical In the Good Old Summertime is accompanied by text which is explicit that this was a woman exploited from childhood by the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios into the ‘clang clang clang’ emblem of American talent, beauty and excellence – a pressure which saw her held at a psychiatric hospital at the age of 25 following an unsuccessful suicide attempt. Though the exhibition doesn’t always go into such detail, there is a profound sense of tragedy and institutional sabotage that looms over these women’s lives and careers, communicating a sense that the incredible power, glamour and celebrity of female entertainers could not exist without significant personal cost, exertions of control and attempts to break them.

The narrative integrity of Diva, however, falls apart in Act II, as the exhibition moves its focus toward the present day. While the segment called ‘Backlash Blues’marvels in delivering an education on the political activities of divas – from Miriam Makeba’s anti-apartheid protest music which saw her exiled from South Africa to Aretha Franklin’s offer of financial aid to civil rights activists and use of her platform to advocate for social and political causes – much of the rest of this Act is nakedly commercial, with arguably premature inclusions. While the likes of Lil Nas X or Billie Eilish have certainly cultivated dedicated fandoms and worthy accolades, the diva is a kind of veneration which speaks to a legacy and distinction that can’t so readily be offered to artists early in their careers.

But this act struggles to animate the more social and political storytelling which gave the costumes life and made Act I compelling. It includes, for example, the outfit Elton John wore on his 50th birthday, designed by Sandy Powell in Louis XIV style and completed with a curly wig, and Whitney Houston’s glittering Marc Bouwer dress for the 1994 Grammys. Without the personality to animate them, these ensembles have a sense of caged glamour about them. Absent the great personas that filled them, you feel like you’re looking at shells. When Kim Kardashian altered and repurposed for the Met Gala a dress worn by Marylin Monroe, she was criticised for preventing a historical piece from being preserved and exhibited; if anything, this exhibition shows what an overloaded and lifeless display of preservation can look like.

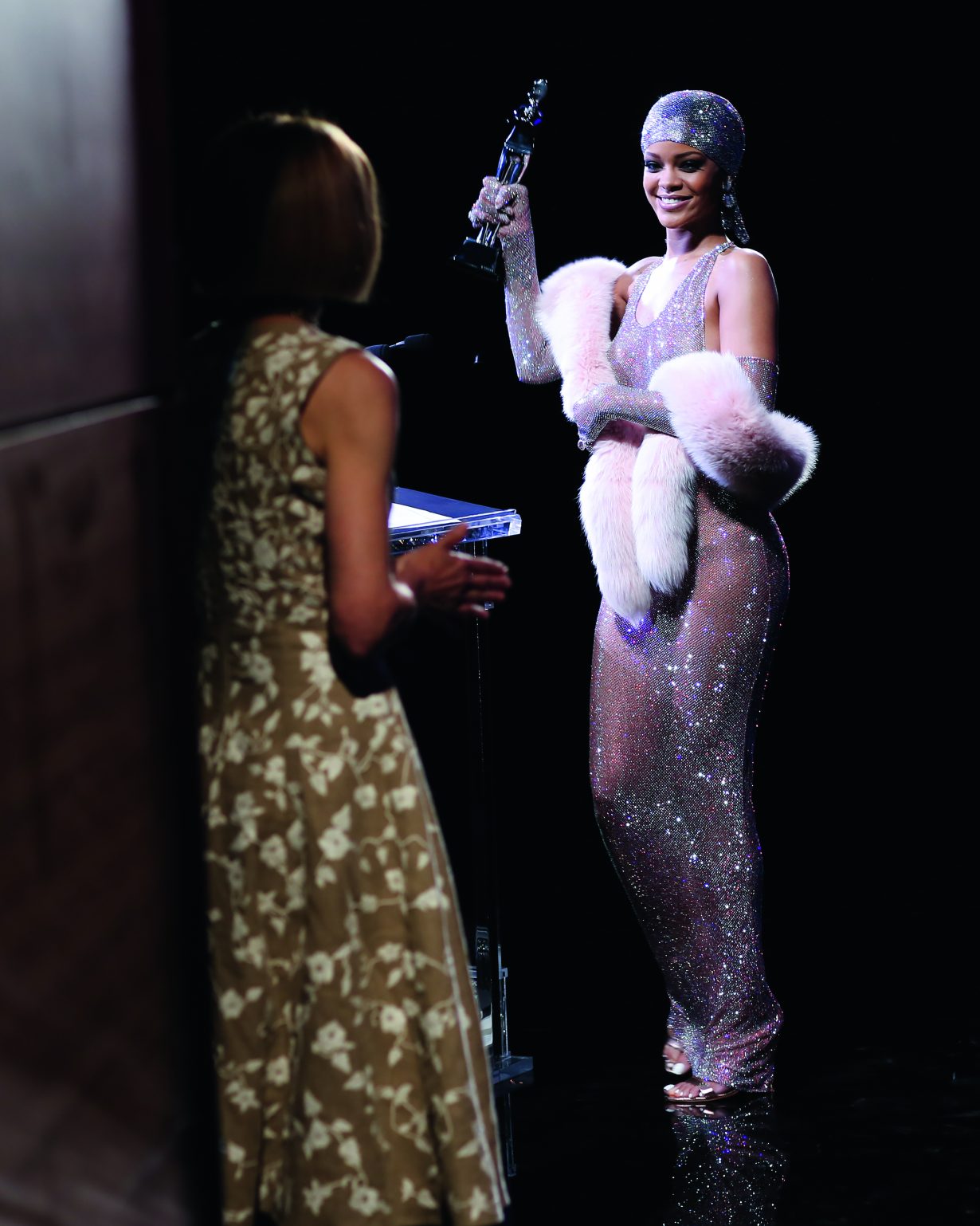

Pride of place in this act is reserved for Rihanna, whose public appearances amount to some of the most iconic fashion moments of the decade – say, a pillowy black Balenciaga overcoat (of sorts) for the 2021 Met Gala, or a sheer gown embellished with Swarovski crystals with a matching durag for the Council of Fashion Designers of America Awards in 2014. This is the daring get-up which sparked the famous line ‘Do my tits bother you? They’re covered in Swarvoski crystals!’; if we’re reclaiming the diva, it should have been written on the V&A’s walls. Even the choice to screen the clip for ‘Umbrella’ (2007), her incredibly tame commercial hit, feels empty considering the alternative of more abrasive, diva-like songs such as ‘Pour It Up’ (2012) or ‘Bitch Better Have My Money’ (2015).

Reclaiming the diva doesn’t mean glossing over the pejorative connotations of the term, but rather showcasing how these entertainers have taken such accusations and thrown them back in the faces of the industries that have attempted to keep them in check. That is what has empowered the image of the diva more than any sum of money. There is little inclusion of Britney Spears, save for a framed 2004 photograph of her performing in Miami with a caption referring to the legal battle she recently won after years spent under conservatorship and the #FreeBritney movement. But Spears is not just the sum of her victimisation – over the years, she’s also been savvy and wilfully provocative. The show could be a reminder that the diva is most alive in these moments, not just in what she wears or who she works with. Wayne Isham, who directed the music video for her 2007 diss track to the tabloid press ‘Piece of Me’, told MTV of how Spears “got there late, showed up and just kicked ass”.

Jason Okundaye is a South London-based writer and author of the forthcoming book Revolutionary Acts: Black Gay Men in Britain.