Do we prefer the unworldly to the world we currently live in?

I

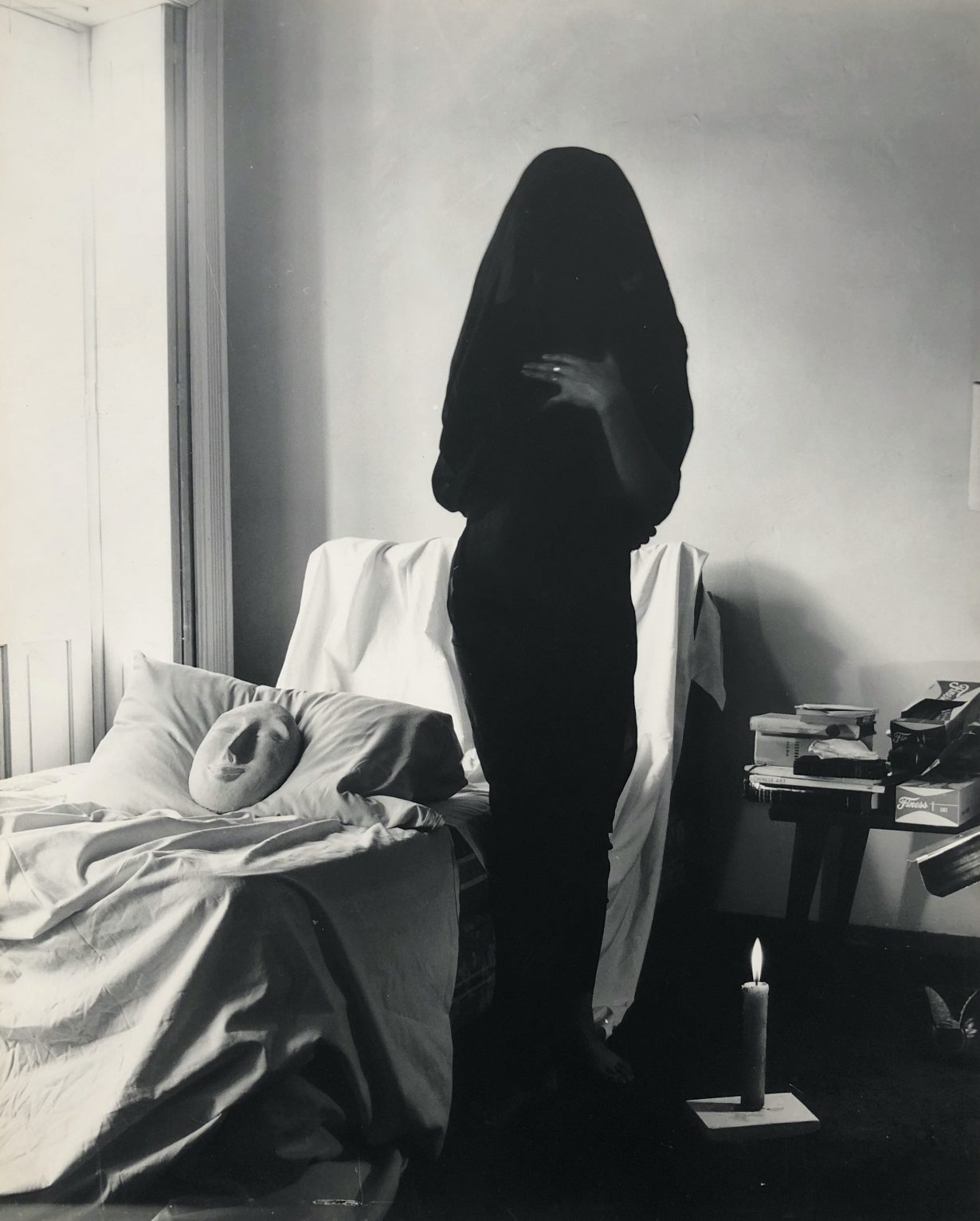

While the spiritual, the mystical and the magical have tended to exist at the fringes of contemporary art, they’ve always bubbled away at the centre of what’s cooking in the alternative and radical subcultures around which that art has circled, and often drawn from. Throughout the modern era, ever since the Symbolists and ‘decadents’ of the late-nineteenth century, Western artists, bohemians and intellectuals have rebelled against the moral and religious orthodoxies by adopting invented or rediscovered occultism from the past, and borrowed from non-Western spiritualism of all kinds: it’s there in the Symbolist artists’ celebration of Satanic iconography; in Aleister Crowley’s neo-paganist ‘religion’; in the Surrealists’ enduring fascination with occult practices, with artists like Maya Deren, who took on the identity of the witch and art as magic; in the adoption of Zoroastrianism by Bauhaus teacher Johannes Itten and of Zen Buddhism by the Beat Generation of John Cage and Allen Ginsberg; in how the Beatles got into the Maharishi and his Transcendental Meditation; in Joseph Beuys’s adoption of the figure of the shaman; in Vienna Actionist Hermann Nitsch’s creation of his ‘Orgies Mysteries Theatre’, bacchanalian celebrations full of purgative ritual and blood-soaked animal sacrifice. Even conceptual artist Sol LeWitt, in his Sentences on Conceptual Art (1968), felt impelled to declare that ‘Conceptual Artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach’. But throughout the twentieth century, though these various countercultures embraced spiritualism and the occult, the contemporary art mainstream has tended to downplay or ignore these artistic interests, as they were often put in the category of ‘outsider’ art, and non-Western spiritual art was relegated to the status of ethnography and superstition.

II

But the last decade has seen a shift of attention in contemporary art: magic, mysticism and spirituality, animism, the figure of the witch, the medium and the shaman, have all made a return to the art mainstream in the work of contemporary artists and thematic shows produced by contemporary curators, while also figuring in academic revisions and rediscoveries. Feminist takes on the occult and spiritual are a common thread: in her videos, installations and writings, Tai Shani has uncovered obscured stories of the place of the witch in European folklore; the late Chiara Fumai incorporated the language of magic, psychic abilities and spellcraft into her patriarchy-baiting performances and videos; meanwhile, attention to spirituality and mysticism has taken on new critical life as artists turn increasingly to the politics of indigenous culture, with some diaspora artists reclaiming precolonial folklores and mythical traditions of their cultural heritage in rejection of Western colonial histories – such as in Korean–Canadian artist Zadie Xa’s exploration of Korean Shamanic culture and origin myths. But these practices aren’t just a matter of artists quoting or appropriating cultural traditions of older or non-Western cultures. In fact these artists are often deeply invested in spiritual perspectives steeped in ideas of expanded consciousness or oneness with the environment, even when they recast forms of indigenous knowledge and ancestral tradition in the technological forms of twenty-first century network culture, as in the work of French Guyana-based Tabita Rezaire.

Art-historical and curatorial thinking has also registered a growing openness to spiritual and mystical perspectives. Perhaps the 2013 Venice Biennale – which included figures such as the occultist Aleister Crowley and the rediscovered spiritualist painter Hilma af Klint (whose canonisation had begun with her first major survey show in Sweden the same year) – was a signal moment, with its more sympathetic and inclusive attention to ‘outsider’ artists, its fascination with art’s relation to ‘supernatural phenomena’ and ‘cosmic awe’, leading to a new attention to the mystical undercurrents of early twentieth-century abstraction. Today, the survey Surrealism Beyond Borders at Tate Modern in London, emphasises the place of mysticism in the work of women Surrealists such as Leonora Carrington and Ithell Colquhoun, criticising the appropriation of indigenous culture in the anticolonial politics of the core Surrealist group, while sympathetically treating Carrington’s interest in Mexican Indigenous myths and practices (she emigrated to Mexico during the 1940s). Carrington is herself the inspiration for curator Cecilia Alemani’s Venice Biennale, which takes its title, The Milk of Dreams, from Carrington’s 1947 book. Meanwhile, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice makes the occult interests of the Surrealists the focus of its Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity. In Britain, a key (re)turn to all things magical was 2009’s exhibition The Dark Monarch: Magic and Modernity in British Art, which highlighted the long arc of esoteric influences among British artists from, amongst others, Colquhoun and Austin Osman Spare to Derek Jarman and Penny Slinger. More recently, 2020’s touring show Not Without My Ghosts: The Artist as Medium continued the spiritualist fascination by assembling artists from the nineteenth century to the present-day, including William Blake, Colquhoun, Spare, Fumai and Susan Hiller.

III

If the counterculture of the 1960s and 70s sent out the heterodox seeds of spiritual and quasi-spiritual alternatives to the modern Western outlook, the last 50 years have seen all these progressively absorbed by mass culture. (It has taken the mainstream artworld a little longer to come round.) If you grew up (like this writer) in provincial England during the 1980s, you’d find that your generation were into ‘New Age’ practices, crystals, dreamcatchers, psychedelic drugs, cannabis, vegetarianism, meditation and, of course, Yoga, the descendants of the 60s Hippy moment. Indie bands were called things like The Shamen, and music occulture segued easily between the witchy medievalist obsessions of Goth to the techno-psychedelic Gaia-consciousness of New Age techno and Rave culture. Today, once countercultural movements are no longer in the margin: Yoga is mainstream, meditation apps are on your phone and googling ‘Meditation for Ukraine’ comes up with numerous people organising group-meditation in order to bring peace and healing to a warzone. At the crankier limits, ‘Magical thinker and activist’ Michael M. Hughes, following up his viral ‘2017 Spell to Bind Donald Trump and All Those Who Abet Him’, is organising a weekly ‘Hex Vladimir Putin’ ritual. (On current evidence, perhaps the spells are working.)

Arguably, then, mystical, spiritual and esoteric interests in art were always there, but have become increasingly visible as mainstream culture has embraced more introspective, spiritual sensibilities. While interest in spirits, magic and mediums may have offended orthodox sensibilities during the late-nineteenth century and early-twentieth century, the fact that artists from Blake to Spare to Fumai can be seen, retrospectively, as part of one long history suggests that mystical sensibilities are as old as modern art itself, only suppressed by a mainstream culture that saw belief in spirits, fairies and non-Western gods as antithetical to the rationalistic, secular and scientific values out of which modernity developed, as much as to the straightlaced morality of orthodox religion.

IV

In her 1991 book Surrealism and the Occult – an early outlier in the contemporary interest in art and occultism – art historian Nadia Choucha traces the esoteric interests of the Surrealists back through to the late-nineteenth century French Symbolist poets and artists. Symbolism, she argues, ‘was elitist and opposed to mass culture, modernity, and materialism. It was born in an atmosphere of political disillusionment and alienation, and its adherents sought inspiration in the past, the exotic, myths and legends, prizing the subjective imagination over external appearance, attempting to create something eternal and universal as opposed to transitory and contemporary.’ It’s a characterisation that could be applied to many artistic countercurrents that followed and, indeed, much of Western counterculture of the last century, and it could easily characterise much of today’s openness to the mystical and the magical in art.

Arguably, what underpins today’s growing sympathy for occultism is the terminally declining influence of a rationalistic, secular modern worldview that is now associated with the depredations of capitalism, patriarchy and ecological disaster. Today’s magical revival is a rejection of the experience of the modern present, along both historical and topographical axes: historical because it reaches back to the worldviews, myths and rituals of the times and cultures before the modern era; topographical, because it privileges those cultures in the present that still exist in contrast to the prevailing forms of social modernity (technologically developed, industrially advanced societies of twenty-first-century global capitalism, inheritors of the industrial revolution and the European Enlightenment).

This shift from historical thinking to magical thinking can also be linked to the growing politics of care for indigenous worldviews that have been long marginalised by Western modernity. In a recent exhibition dealing with the museum care of artefacts belonging to older, sometimes disappeared cultures and societies, artist Gala Porras-Kim suggests that the spiritual aspects of an artefact should continue to be respected by modern curators: Egyptian burial artefacts, for example, now held by the British Museum, could be presented in such a way that respects the ancient Egyptians’ belief in their afterlife – by, for example, repositioning a sarcophagus so that it points towards the rising sun, in accordance with Egyptian burial custom. The growing conflict in contemporary discourse between modern epistemology seen as Western or colonial, and the validity of indigenous cultural traditions, was sharply revealed last year in the controversy over an open letter by academics at the University of Auckland, who questioned whether Māori traditional knowledge could be placed on a par with modern science. More broadly, the notion that traditional and customary beliefs and mythologies are as valid as empirical and universalising forms of modern knowledge underpins the ambiguous return of magical thinking everywhere.

V

As it reaches back to the past, the new magical thinking also projects into the future. Artist and writer Alice Bucknell has championed a group of artists monikered the ‘New Mystics’ (which includes Xa, Shani, Rezaire, Ian Cheng and Haroon Mirza, among others) for their work’s fusion of technology and mystical perspectives, linking it to anticapitalist and postcolonial politics; ‘It would be a mistake to consider these works a nostalgic look back to simpler times,’ Bucknell wrote in ‘The New Mystics: High-Tech Magic for the Present’ (in Mousse magazine in 2019). ‘Instead, these artists are using the atmospheric potential of new technology to resurrect ancient belief systems bleached out of history, repositioning them as a powerful communal cipher into the present. Inside their ambient installations, race and identity politics are explored, forgotten folklore is resurrected, and the violent superstructures of colonialism and capitalism are critiqued’. A key point Bucknell makes is on the question of cultural appropriation; ‘The mystical has transitioned – or transcended – its abuse as an appropriated symbolic affectation by western art circles in the twentieth century to an intersectional social process in the present. (Instead of a white male artist hanging out in a Manhattan gallery with a coyote under the name of shamanistic experience, artists of color can reclaim and explore their diasporic heritage.)’ Here, mystical attitudes become positive simply because they are the supposedly authentic cultural property of marginalised and historically oppressed minorities, now reinvented in the futuristic millennial aesthetic of digital culture. It’s a descendent of the ‘Techno-Paganism’ that early internet critics such as Erik Davis and Mark Dery characterised in the mid-1990s, merged with a more recent emphasis on ecology and postcolonialism.

VI

Magic returns because, in the last two or three decades, the ideas that underpinned modern society, philosophically and politically, have lost their traction and legitimacy. If modern societies are the product of that long period of modernity that started in the West – industrial, immensely productive, technologically sophisticated societies that have flourished all around the world, raising people out of poverty, extending life, health and liberty – few would defend those achievements today. That model of the modern society is now experiencing a profound loss of faith, a kind of cultural exhaustion in which we instead see modern societies as extractive, domineering and ecologically unsustainable. If ideas of reason, rational action, science and progress are in decline, and if the human culture and consciousness formed by those ideas is dangerous and destructive, then the only alternative can be a return to the premodern: or rather not a return, but a dissolution of modernity and modern ways of thinking in the present. This is the cultural driver for the revival of the sacred and the mystical in art. Magic replaces science, belief replaces knowledge, ritual replaces rational action. Circular time replaces history. And as a corollary, the idea of the distinctly human subject, a being different in thought and action to the rest of nature, is dismissed as the hubris of the colonist and oppressor. While much ecological thinking grounds itself in science, it leads back to what is really the premodern mystical view of humans as participants intertwined with nonhuman entities as part of a greater, harmonious ecosphere. Much of the new mysticism in art regularly invokes the old countercultural tropes of psychedelic transcendence and the loss of the individual self to the collective and a greater planetary entity – but this time it’s in VR.

VII

In 1947, the theorist Theodor Adorno, by then exiled to America as a result of the Second World War, wrote ‘Theses Against Occultism’, a polemic analysis of the forms of contemporary occultism that he found in late-capitalist American culture, a part of his wider study of fascism and its relationship to irrationality. He opens with the assertion that ‘The tendency to occultism is a symptom of the regression in consciousness’, arguing that while people no longer truly believe in occult forms, their reappearance in capitalist mass-culture – as newspaper horoscopes, palm-readers, ‘number mysticism’ and paranormal pseudoscience – represented an alienated retreat from a reasoned understanding of capitalist society; fantastical ways for people to project a sense of control and certainty onto a society that presented itself as fundamentally incomprehensible. ‘By its regression to magic under late capitalism, thought is assimilated to late capitalist forms’, he writes, while ‘Occultism is a reflex-action to the subjectification of all meaning, the complement of reification’. What Adorno means is that as capitalism becomes ever-more strange and inaccessible in its workings and ever more impervious to political change, people turn to spiritual inner worlds and mystical outer worlds. While much of the new magical thinking returns to the old countercultural aspiration to ‘expanded consciousness’, and a psychedelic oneness with the world, it’s really a ‘regression of consciousness’, a rejection of facing reality as it is, a retreat from trying to make sense of it and acting to change it. Magical thinking is a projection of wish-fulfilment onto a reality we’d rather withdraw from, into one where the troubles and contradictions of the modern world are resolved by merging the imaginary and the real – the ‘subjectification of all meaning’. Art has always walked the line between the real and the imaginary, but in the contemporary return of the magical, the unworldly is the world we’d rather live in. We might not really believe in magic, but we don’t really believe in anything else, and we’d prefer not to break the spell.