Park Chan-wook’s detective noir, which premiered at Cannes one year ago, corrodes the boundary between image and the ‘real’ world

It’s a year since cult Korean director Park Chan-wook’s Decision to Leave premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. While generally a critical success, many felt that it was not up there with his best films, such as Oldboy (2003) and The Handmaiden (2016). But the film is without doubt notable for the way in which it single-mindedly pursues a single theme on an aesthetic, narrative and structural level. And not just, as Park has acknowledged in numerous interviews, for the influence of Alfred Hitchcock’s noir classic Vertigo (1958).

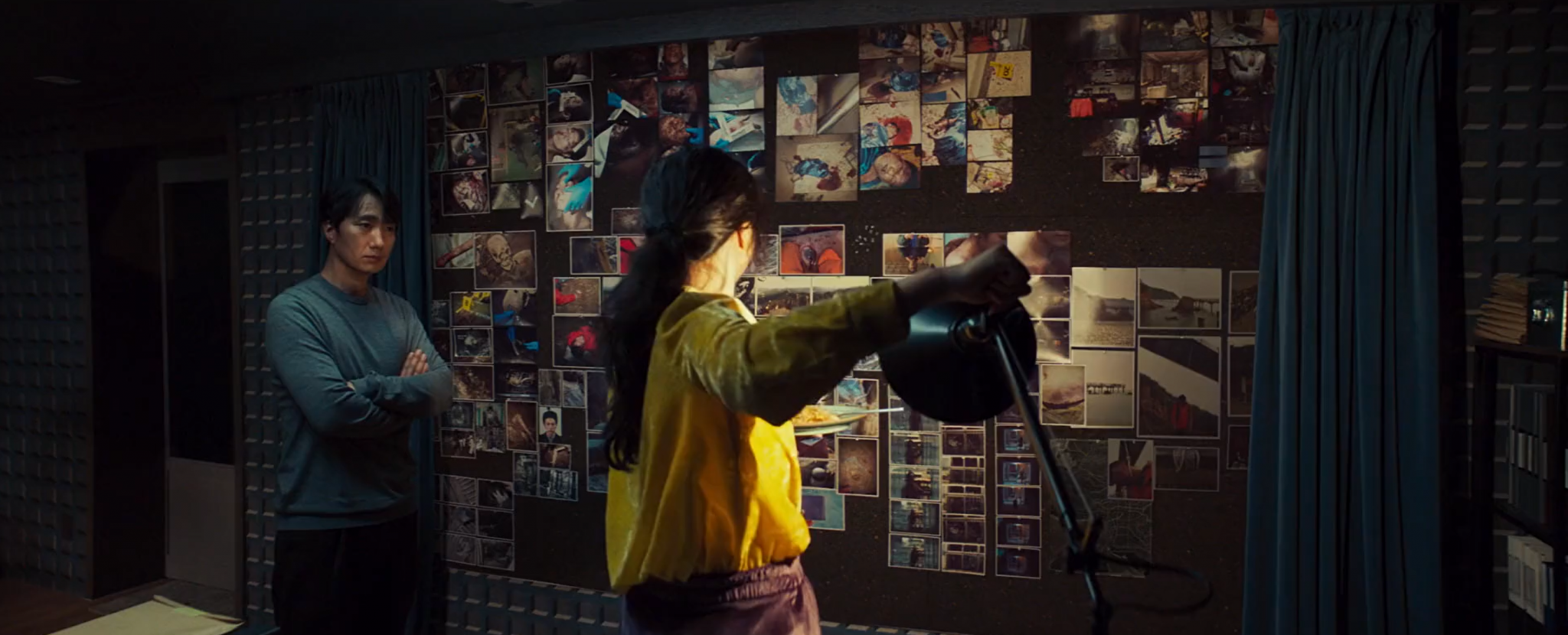

The storyline of Park’s film is simple: Hae-jun is beguiled by the beautiful and mysterious Chinese emigrant Seo-rae, who turns out to have murdered two husbands (Ki Do-soo and Im Ho-shin) and killed her terminally ill mother with fentanyl. These events lead to Seo-rae’s suicide and Hae-jun’s final dismay at losing her. But what is striking in the film is how decay infects all the various levels of its reality. What begins with the image of a simple piece of mould on a wall ends up spreading everywhere. The rot corrodes the boundary between image and the ‘real’ world – the act of looking and of being looked at. During the first half of the film, every time we see a corpse rotting, wounds festering or scratches encrusting, we do so through its reflection via live images on a monitor or a phone or an X-ray. From there the images creep onto the detective’s private photo wall – a memento mori of murder scenes. And then the rot seems to spread, from the pictures and screens to the ‘real’ world. Park forces the audience to witness the materiality of the rotting state by zooming in on a fly landing on a dead human’s eye, or on mould growing on the wallpaper in the detective’s pristine villa in the misty town of Ipo, or on the new bruises (signs of damage) that keep appearing on Seo-rae’s torso. Moreover, as the movie progresses, Hae-jun becomes obsessed with looking at dead bodies. Eventually he is overwhelmed by them.

But it doesn’t end there. The rot that Park sinisterly manipulates throughout spreads from the imagery to the narrative itself, firstly in the corrupting synchronisation between Seo-rae’s crimes and her love. The fall of her first husband, Ki Do-soo, from the hill must be timed perfectly by Seo-rae in order that it trigger the chain of events that causes Hae-jun to fall in love with her. Indeed, it’s timed so perfectly that Hae-jun also comes to believe that he is an accessory to Seo-rae’s murder, leading him to utter the words “bung-goedwaess-eoyo” (collapse, breakdown).

Then the rot continues its spread as this new love leads directly to a second murder. If Seo-rae had not poisoned the Chinese immigrant Sa Cheo-Seong’s bedbound mother, Cheo-Seong’s hatred of Seo-rae’s second husband, the financial swindler Im Ho-Shin, who has defrauded Cheo-seong’s mother of millions of dollars, would not grow to the extent that he ends up killing Ho-Shin. But Seo-rae has to do so in order that the murders continue to be related to seduction, staged in order that Hae-jun will see the corpse, as the rot is ‘lured’ into a body that is lacerated and exposed to open air. Even more so, the rot continues, not even halting after Hae-jun sacrifices his ‘heart organ’ (there are two different words in Korean, one being ‘heart’ as a romantic concept and the other referring to the heart as the organ) during Seo-rae’s suicide on a cold beach near Manchuria. It’s a scene that is portended early in the film, when Seo-rae speaks Mandarin to Hae-jun through a translating app that mistranslates her Mandarin words ‘bring the detective’s heart to me’ into the Korean for ‘bring the detective’s heart organ to me’.

Toward the end of the film, we are presented with the image of a fog covering the sea, perhaps a metaphor for the blanket of fungus that has spread throughout the film.

ArtReview is partnering with Asymmetry to publish a series of cultural reflections by the foundation’s fellows