Or, what Beautiful World, Where Are You shares with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s ‘Tax the Rich’ Met Gala dress

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve probably clocked that Sally Rooney has a new novel out. The millennial Irish novelist often touted as the definitive ‘millennial Irish novelist’ has, to much fanfare, released her third book in four years, Beautiful World, Where Are You (2021). It is – spoiler alert – about a millennial Irish novelist, who, having published two books to great acclaim, is struggling with the pressures of fame. As the saying goes, write what you know.

To those familiar with Rooney’s work, much of Beautiful World, Where Are You will feel, well, familiar. Like her 2017 debut novel Conversations with Friends, it is about four people who ground their interlocking ‘it’s complicated’ relationships in discussions of sex, art, politics, gender, forgiveness and fantasy. Like Normal People (2018), it’s about power dynamics between ostensibly mismatched couples and miscommunication. It features a thin writer riddled with self-hatred and a beautiful, lonely copyeditor. It features a complicated relationship with an older man, whose ‘fantasy is that you’re really helpless […] and I’m like, telling you what a good girl you are’, and a complicated relationship with a handsome, sociable, working-class lad, who asks ‘do you hate the word ‘fuck’?’ before asking to fuck, and says things like ‘you’re very small with your clothes off’ at the moment of penetration. I read it in a day.

Of course, this is a somewhat reductive summary of a book that – as readers have also come to expect from Rooney – attempts to use intimate relationships as a prism through which to refract contemporary concerns. It’s not about sex baby, it’s about capitalism. Or, it is about sex, but as a consolation for living through global crisis; love at the end of the world. Does that also seem reductive? If so, that’s because Beautiful World, Where Are You often reads like Rooney’s clunky attempt to answer her critics – those accusing her of being overly sentimental and insufficiently political. If you’re a Marxist, the argument goes, why does the leftism of your characters feel so shallow, gestural, or superficial?

This time, Rooney wants to make things more explicit. So, for half the book, we have an intellectual friendship between two women, unspooling across an email exchange in alternating chapters. Alice and Eileen’s lengthy emails form an extended Socratic dialogue, as they question each other’s outlooks on success, the climate crisis, the collapse of civilisations, rent, religion, the Late Bronze Age, and Audre Lorde’s 1978 essay ‘Uses of the Erotic’ (to name only a handful of topics covered). Scattered amongst these commentaries are reflections on – what else – their respective romantic encounters with the central male characters, Felix and Simon. These emails are the closest the novel gets to interiority, for interspersed with them are chapters narrated from an omniscient third-person point of view – a new technique for Rooney, perhaps signalling a desire to swap the extreme, even claustrophobic intimacy her writing is known for, for distance. In Beautiful World, Where Are You the reader is held at a remove.

I respect the intention. The intellectual lives of women are still under-recognised in literature, and, by giving equal prominence to her central characters’ shifting ideas as to their evolving relationships, Rooney seems to assert a belief that, despite what her critics may imply, the line between the ‘sentimental’ and the ‘political’ is always blurry at best. ‘I was interested in […] how their ideas inform the relationship,’ Rooney said recently, ‘and how the particularities of their dynamic inform the development of their ideas.’ ‘So of course in the midst of everything,’ Alice writes in one missive, ‘the state of the world being what it is, humanity on the cusp of extinction, here I am writing another email about sex and friendship. What else is there to live for?’ As these women attempt to negotiate how to live in a world that can seem anathema to their happiness, the personal and the political necessarily intersect.

The problem with this oscillating omniscient and epistolary form is that it falls flat. The absence of their interiority means the male characters remain static – sketchily drawn archetypes that never cohere into fully realised personalities. Felix seems mean and Simon seems boring. While Rooney remains a skilled technician of the ‘will-they-won’t-they’ narrative arc, I felt no investment in the characters’ relationships, as their actions and reactions progressively resembled little more than thought experiments to be dissected in the subsequent email exchange. Furthermore, the women seem to converge – their supposedly unique narrative voices increasingly indistinct. Who is thinking what here? Who is writing to who? Naturally perhaps, given the tendency for women authors’ work to be read autobiographically, Rooney rails against suggestions her characters are merely her reflections. Yet, frequently Beautiful World, Where Are You feels like a conversation Rooney is having with herself. More than anything, it is a novel about literary production – one that questions but ultimately justifies its own creation. Beautiful World, Where Are You is Rooney’s book about her own career and celebrity.

‘If novelists wrote honestly about their own lives, no one would read novels – and quite rightly!’ Alice exclaims in one particularly strident email. ‘Maybe then we would finally have to confront how wrong, how deeply philosophically wrong, the current system of literary production really is’, she continues, ‘how it takes writers away from normal life, shuts the door behind them, and tells them again and again how special they are and how important their opinions must be […] I don’t say this lightly: it makes me want to be sick.’ While Rooney may not straightforwardly be Alice, she certainly shares her protagonist’s horror of the publicity machine. Alice takes aim at the cycle of ‘weekends in Berlin’, featuring ‘four newspaper interviews, three photoshoots, two sold-out events, three long leisurely dinners where everyone complained about bad reviews’. and in the course of her own cycle of interviews, photoshoots and sold-out events, Rooney has taken aim at the culture of literary fame. Suggesting ‘the way that celebrity works in our present cultural moment is that particular people enter very rapidly […] into public life, becoming objects of widespread public discourse, debate and critique,’ Rooney argues such figures ‘just randomly happen to be skilled or gifted in some particular way, and it’s in the interests of profit-driven industries to exploit those gifts and to turn the gifted person into a kind of commodity.’ And, of course, being transformed into a commodity is something ol’ Sally knows all too well.

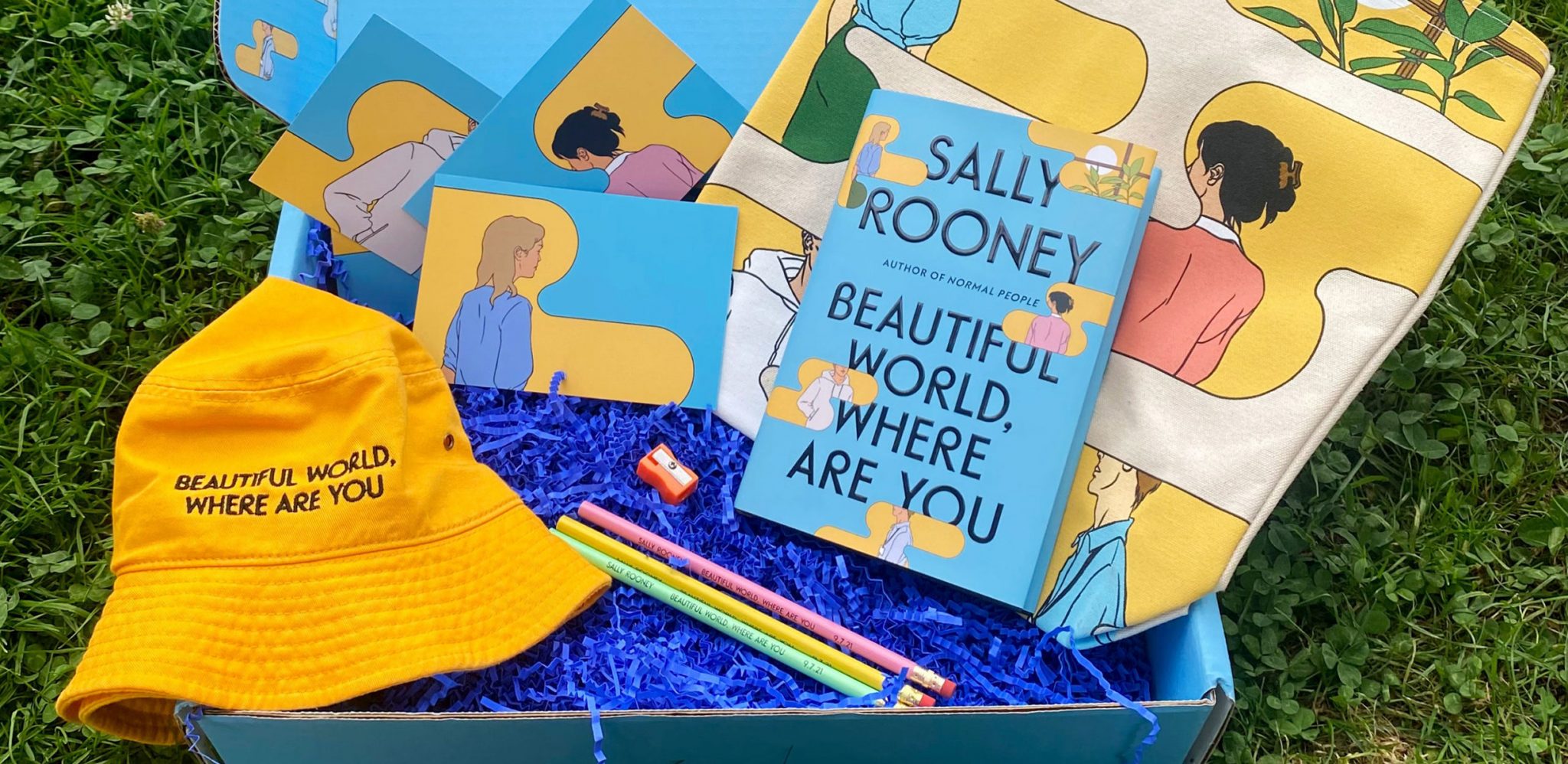

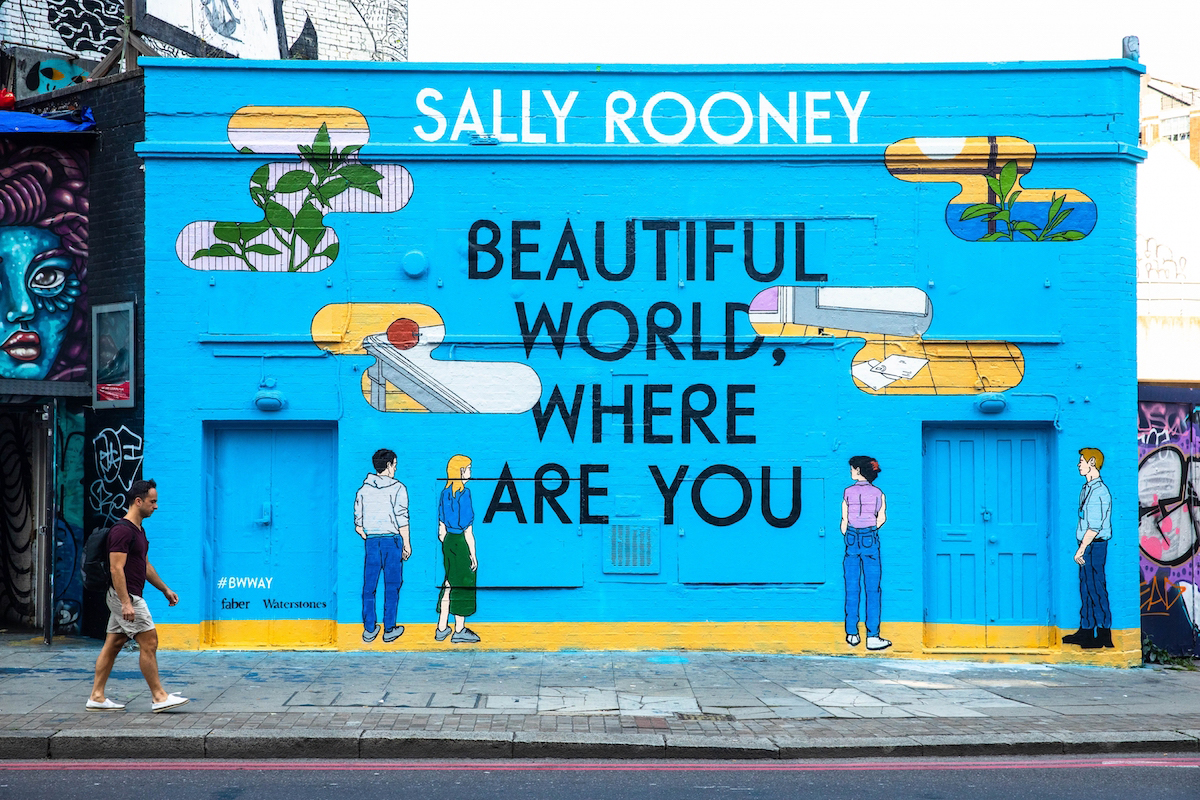

In the months leading up to its release, Rooney’s US publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, distributed tote bags featuring the novel’s cover illustrations, and yellow bucket hats emblazoned with the title to celebrities, journalists and other ‘literary influencers’. Lena Dunham, Lucy Dacus, and Maggie Rogers shared photos of the book and its merch on social media. Sarah Jessica Parker was photographed reading it between takes for the Sex and the City reboot. Soon, the tote bag was fetching up to $80 online; an advance proof sold on eBay for $209.16. On publication day the hype machine went into overdrive, with the UK publisher Faber launching a Sally Rooney pop-up shop in London’s Shoreditch, and bookshops opening early to cater for long queues of, mainly, millennial white women eager to succumb to the Rooney industrial complex. How does Rooney feel about all this? Does it make her ‘want to be sick’?

Is it ironic that Rooney’s most-hyped and commodified book contains long explicit passages denouncing the literary world and the cult of the author? Or, is it an attempt to have her cake and eat it too? When images of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s ‘Tax the Rich’ Met Gala dress ignited the internet last month, I couldn’t help but think of Rooney. Doubtless there is a delicious appeal in subverting and smuggling radical politics into the world of celebrity. Still, it’s difficult to see how either ‘statement’ does more than prove how leftism is recuperated, co-opted, and incorporated by mainstream culture and capital. Whether consciously or not, the oppositional postures of AOC’s dress and Rooney’s book work to enhance each woman’s brand. In a neoliberal marketplace, ‘nonconformity’ is an asset. Alice may liken celebrity culture to ‘a malignant growth’, but Rooney still has a pop-up shop in Shoreditch bearing her name.

Rooney’s epigraphs are always revealing, and in Beautiful World, Where Are You she employs one from Natalia Ginzburg’s The Little Virtues (1962): ‘When I write something I usually think it is very important and that I am a very fine writer. I think this happens to everyone. But there is one corner of my mind in which I know very well what I am, which is a small, a very small writer. I swear I know it. But that doesn’t matter much to me.’ Ginzburg’s work suggests that even in times of political unrest, it’s small, human intimacies that define our lives. So, the state of the world being what it is, here Rooney is writing another book about sex and friendship. What else can she do?

In the end, it’s just a shame Beautiful World, Where Are You leads to such banally conventional conclusions. The men and women couple up, and the women start writing again. Perhaps this is one way to quell Rooney’s fears about the current system of literary production: by saying her work isn’t that special at all.