From the Sharjah Biennial to a new outing for Sonia Boyce’s acclaimed Venice Pavilion, our editors on the exhibitions around the world to catch this month

Wangechi Mutu: Intertwined

New Museum, New York, 2 March – 4 June

Wangechi Mutu’s plastic universe is haunted by hybrid Black female figures that are as nightmarish and grotesque as they are hypnotic. The Kenyan-born American artist’s collages in particular have a Hannah Höch-esque quality to them, surgically assembling cutouts from fashion, travel and porn magazines into portraits of dangerously mutating figures that conjure the lingering psychological and physical traumas of colonisation and the violence of a patriarchal society on the Black female body and its image. Featuring over 100 works, this survey traces how Mutu has, over the past twenty-five years, translated her haunting visions into painting, film, performance and sculpture, creating a distinct cosmology and language that feed off feminist studies, Afrofuturism and an acute awareness of environmental collapse. Louise Darblay

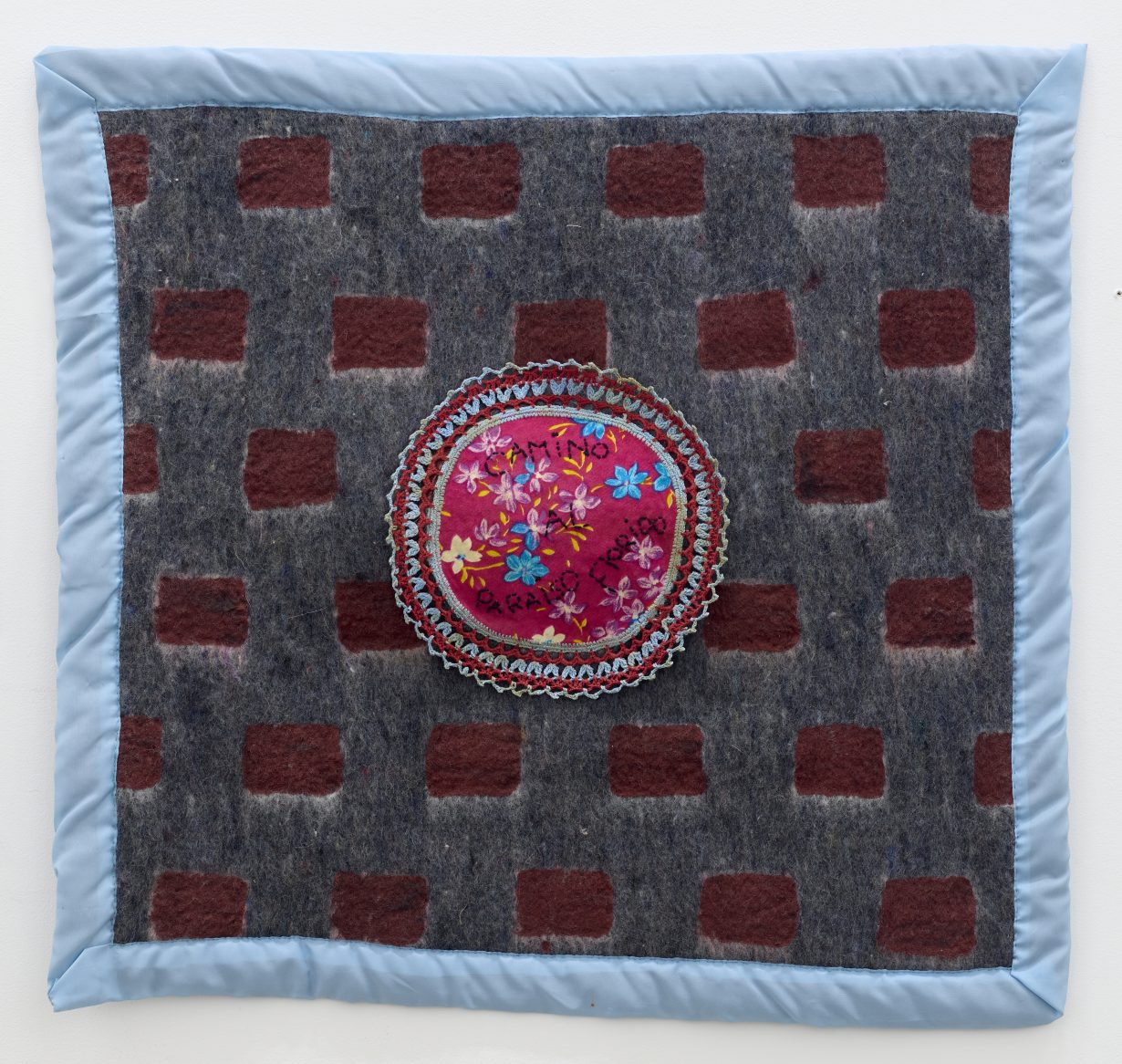

Feliciano Centurión: Telas Y Textos

Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 6 February – 19 May

The origins of Feliciano Centurión’s textile work can be found in Paraguayan colonial history, in which the country’s modern culture is a mix of the European Baroque brought over by Jesuit missionaries and Guarani indigenous aesthetics and beliefs. His most prolific period was after he moved from his native San Ignacio across the border to Argentina, preceding his early death of an AIDS-related illness in 1994. Having originally dabbled in painting, Centurión looked instead to found fabric, and moved away from erotic imagery, to embroidered text-based work. In this survey of his last years, coasters, aprons, kitsch tablecloths and the type of blankets favoured by the homeless population, find themselves vehicles for phrases that address both the artist’s sexuality and religion. They were tender and less confrontational – objects that hover between relic and craft – a response to his illness. Te quiero (I love you) reads one; while others say Descansa tu cabeza en mis brazos (Rest your head in my arms); El cielo es mi protección (Heaven is my protection) and Tu presencia se confirma ennosotros (Your presence is confirmed within us). The saddest were made on pillowcases, sewn from the confines of his hospital bed at a time when no treatment was available. Oliver Basciano

Francis Alÿs: Juegos de niñxs, 1999-2022

Museo Universitario Arte Contemporaneo, Mexico City, 11 February – 17 September

When unaccompanied by your own ward, it’s generally quite creepy for an adult to watch children play. Yes, they are cute; no, you cannot stare. Francis Alÿs’s forthcoming exhibition Juegos de niñxs at Museo Universitario Arte Contemporaneo in Mexico City, however, is an ethnographic exploration of kids – generally from the Global South – at play. Alÿs has been documenting digital-free game playing since 1999, claiming that these ‘subterranean cultures’ are at risk of extinction. While the project at first glance seems to have a ‘utopian aura’ (what is more joyful than children around the world having fun?), there is something more sinister at play here, particularly in the dynamics of Alÿs’s framing of the project. Intended for it to act in part as an anthropological project, I’m sceptical: a focus on children and cultures from ‘underdeveloped’ nations firstly prescribes to the Global North’s hegemonic understanding of youth as an era of innocence; secondly, it ‘others’ these customs by turning them into Fine Art videos in their focus of showing children from other places; and thirdly, I wonder what are the implications of children in fine art. Nonetheless, Alÿs’s Juegos de niñxs demands further investigation and thought. And ok fine, my grumpy heart does warm a little when I see the joy on kids’ faces. Marv Recinto

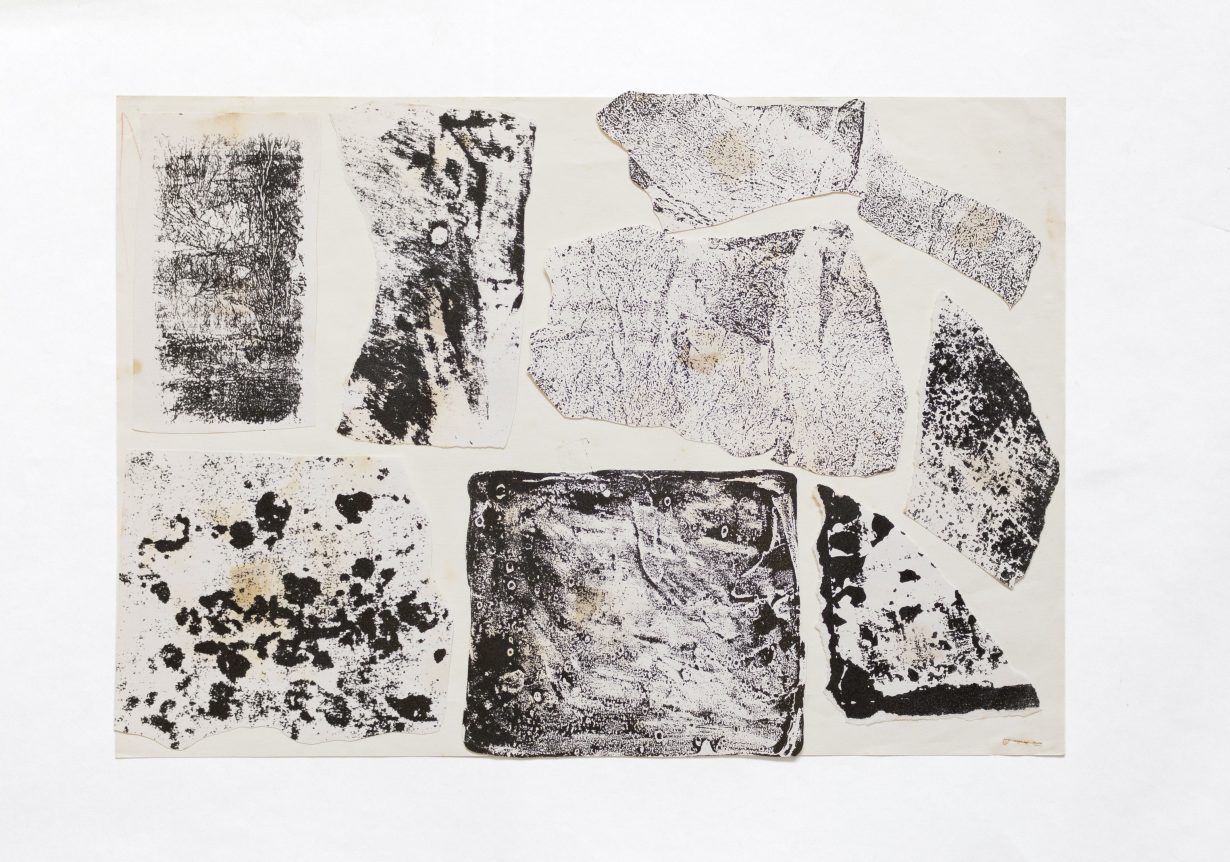

Carmela Gross: Carimbos

Instituto de Arte Contemporânea, São Paulo, 6 February – 6 May

For fifty years the Brazilian artist’s work has dealt with ideas of infrastructure, whether it’s direct urban interventions (altering the Portuguese paving stones in the central square of the city of Santa Caterina or creating a series of cascading steps down to the river in Porto Alegre), sculptural renditions of typical Brazilian city motifs (from the Red, 2018, in which she painted over a popcorn sellers’ trolley, to the less cheery works of the late 1960s in which the artist recreated the ad-hoc dwellings of the homeless). In the late 1970s however Gross commissioned a series of ink stamps, the tool synonymous with bureaucracy, to produce two years of collage works of ink paper. Brought together, along with the stamps themselves, this exhibition emphasises questions of seriality. Gross would first make a single brush stroke which she would then use as the basis of a woodcut stamp, that unique gesture methodically repeated in the end composition. While in her sculpture work, Gross created breaks in the everyday function of the city, here she embodies the machinic repetition of capital, the artistic gesture made clean and efficient. Oliver Basciano

Ingela Ihrman: Nocturne

Gasworks, London, 2 February – 30 April

At Gasworks, Malmö-based artist Ingela Ihrman fuses craft traditions, cosplay and a delight in the absurd to draw our attention to the essential interconnectedness of life-forms. Here, she promises to do this by way of a specially commissioned ‘wearable sculpture’ which will allow us ‘to merge – quite literally – with nature’, embodying the digested remains of a nature documentarian’s deadly encounter with an anaconda; elsewhere, a film takes us inside the aforementioned serpent’s digestive tract. Meanwhile, among other – at times, comic – interventions, Ihrman has turned the gallery into a pitch-dark cavern, transforming visitors into ‘nocturnal creatures’ who must navigate the exhibition by echolocation. En Liang Khong

Sonia Boyce: Feeling Her Way

Turner Contemporary, Margate, 4 February – 8 May

‘It’s about bringing people together’, Sonia Boyce told ArtReview last year in advance of her presentation at the British Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale. ‘It’s about improvisation; and hopefully it’s a journey for the visitor through different kinds of spaces.’ The artist’s exhibition Feeling Her Way went on to win the Golden Lion for her efforts; later in the year, Boyce made her way into this magazine’s Power 100 ranking of 2022’s artworld figures (‘Boyce has long carved her own path’, the list noted of her entry). For those who missed it, Boyce’s choral installation – which deploys tessellating wallpaper, geometric sculptures, and films featuring the work of five musicians (Jacqui Dankworth, Poppy Ajudha, Sofia Jernberg, Tanita Tikaram, and Errollyn Wallen) – arrives at Turner Contemporary this month: it’s a powerful exercise in improvisational flow, dissonance and harmony, and an expression of belonging. En Liang Khong

Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present

Various venues, 7 February – 11 June

What, exactly, does ‘thinking historically in the present’ mean? The theme of this year’s Sharjah Biennial was originally planned by the late curator Okwui Enwezor (Venice Biennale, 2015; Gwangju Biennale, 2008; Documenta 11, 2002), whose research spanned the history of museum practice and decolonisation. Hoor Al Qasimi, the director of Sharjah Art Foundation, has taken up the mantle as curator for this edition with the view of delivering Enwezor’s conception for the biennial, one that would reflect his thinking that contemporary art exhibitions provide visitors with the opportunity to ‘engage with history, politics and society in our global present’. It’s still sort of unclear what the theme means, but the title is suitably vague for a largescale exhibition in which over 150 artists and collectives are participating. And it seems that Al Qasimi will be taking an approach that ‘privileges the role of intuition and incidence’… (Good thinking – something for everyone!) What is certain (and which is usually one of the more exciting aspects of biennials) is that there will be 70 brand new artworks including 29 specifically commissioned works by artists such as John Akomfrah, Sammy Baloji, Carolina Caceydo, Destiny Deacon, Mona Hatoum, Isaac Julien, Ibrahim Mahama, Wangechi Mutu and Carrie Mae Weems; meanwhile artists including Brook Andrew, Hassan Hajjaj and Tania El Khoury will be presenting live performances and film screenings during the opening week. Fi Churchman

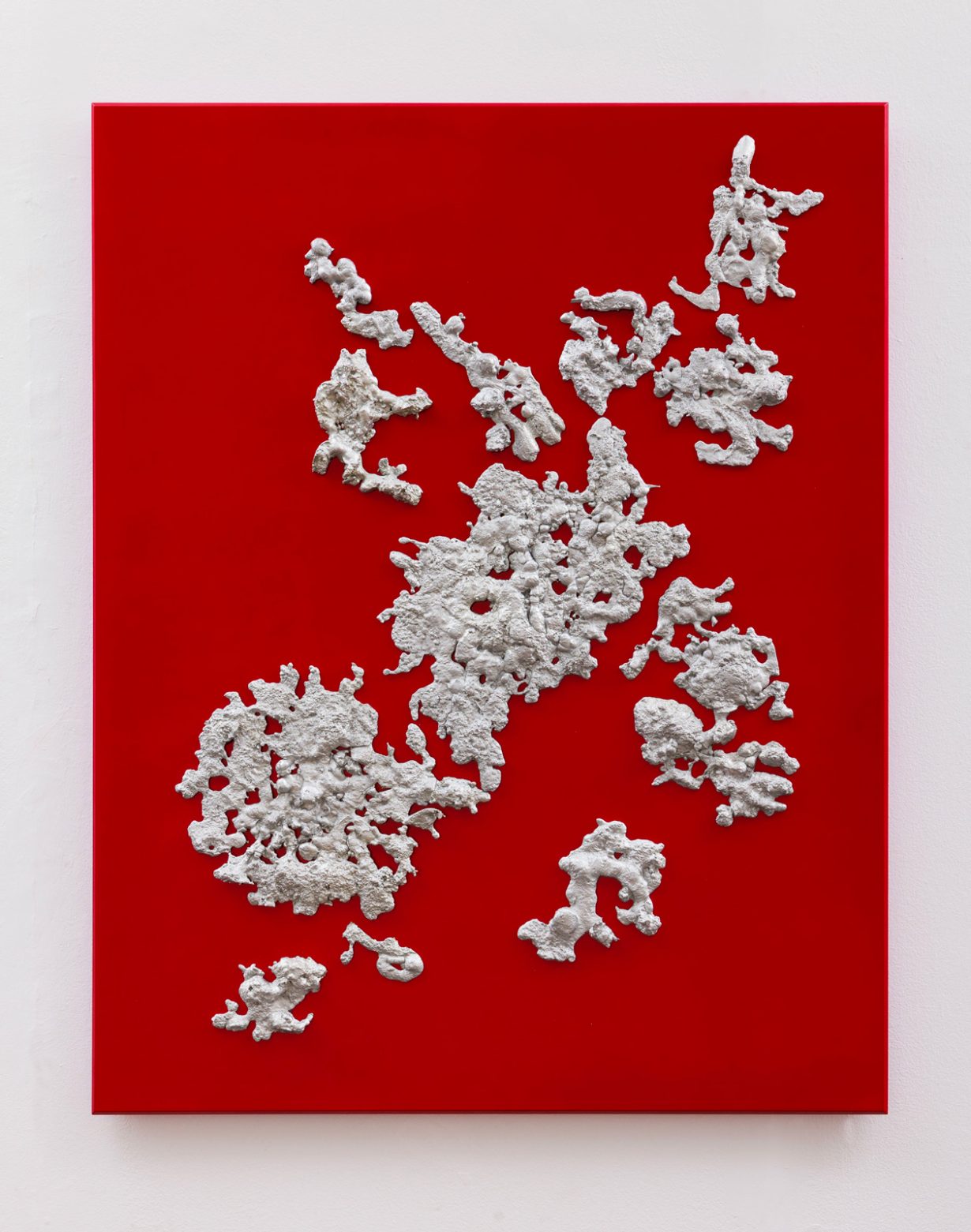

Yasmina Alaoui: BINATNA (Between Us)

Comptoir des Mines Galerie, Marrakech, 9 February – 30 March

On 11 February, the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair marks its tenth anniversary by returning to Marrakech for the first time in three years. But when the suits, sunglasses and chequebooks (sorry, ethereum wallets) descend on La Mamounia hotel, escape the tetris-walled fair and make a dash for the Gueliz’s Comptoir des Mines Galerie. New York-based, French-Moroccan artist Yasmina Alaoui has built a body of work addressing the female form, and the inequalities it suffers, at the crossroads of combined cultural identities – alternatingly in mixed-media works, sculpture and photography. Alongside her more immediate gender works, her interaction with ideas of biology and civilization are promising: a sense of archeology persists from her earlier series Sediments, where large-scale, multi-panel works of found objects (here, in Fertilités, underwear) seem excavated as much as created; Bas-reliefs in resin cast microbial, almost fungal forms – from which the implication of figures emerge – against poppy painted woodblocks. But the realities of the present world are rarely shirked: Benedictions (2022) – a series of landscapes of painted finger-like casts that, filling the frame, seem to swirl like sea anemones – is dedicated to ongoing illiteracy rates that keep Moroccan women in manual labour. Alexander Leissle

Boloho: BOLOHOPE

Hanart TZ, Hong Kong, 18 February – 6 April

Apparently you can eat the core of a jackfruit – though most people toss that part away. In the last couple of years it’s been all the rage as a meat substitute: BBQ jackfruit ‘pulled pork’! Jackfruit ‘chicken’ drumsticks! To be honest, I’d throw all of it in the bin, and not just because jackfruit ‘sushi’ sounds unpleasant, but because the stuff gives me an anaphylactic reaction. Now that, my friend, is a legit reason. The one kind of jackfruit I could get on with, however, comes in human form and is known as the artist collective BOLOHO (which is the romanised Cantonese word for a jackfruit core, and presumably a symbol for the sprawling collective because the entire fruit houses hundreds of individual edible ‘flowers’). BOLOHO recently presented work at Documenta 15, having installed a Hong Kong-style cafe in a disused factory building to which invited artist-participants added their own work reflecting on ‘contemporary workplace realities and traditional family culture’. Here, the collective showed a self-produced sitcom titled BOLOHOPE in response to the ‘sentimental narratives bound by traditional family values’ common in East-Asian popular television, as well as a publication and a series of drawings and paintings that highlight the ‘underrated ‘art’ of many everyday practices, such as cooking, gardening, sewing, housework, and child-rearing’. BOLOHO moves its Documenta offerings to Hanart TZ this month, continuing the discourse around the ‘interconnectivity’ of Southern Chinese culture via textiles, installations, performances and video. Fi Churchman

Dorcas Tang 邓佳颖: Love Me Long Time

4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, 25 February – 9 April

When Reina told a random bartender she was just ‘hanging out’ with friends, he replied ‘Yeah you are, you Asian slut’. Dorcas Tang’s forthcoming exhibition Love Me Long Time at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art interrogates the fetishism of Asian intimacy, particularly in light of sustained racial and gendered violence against the community. Reina’s account is one of the many Tang uncovers through her interviews with Asian diasporic and Asian Australian women and non-binary people for this ongoing audiovisual project. Many conversations are sincere, intimate and at times amusing: Lydia, for example, recounts asking her Korean mum whether the new guy she’s been dating makes her come. Since Love Me Long Time began online, Tang’s exhibition and programming reaches out to the community by taking a collaborative, hands-on approach with discussions and reading groups in the hopes of encouraging transparency, trust and care. Marv Recinto