From Ed Ruscha in New York to Tarek Atoui in Sydney, our editors on what they’re looking forward to this month

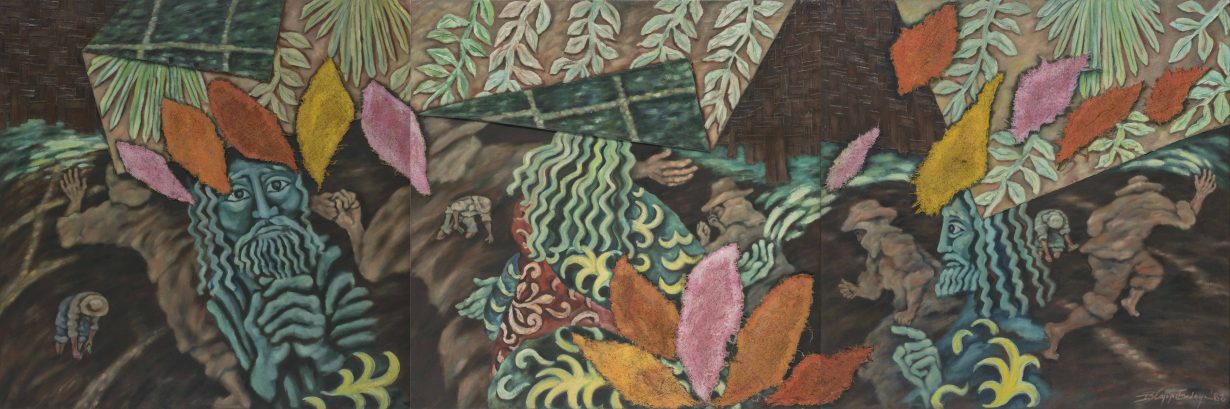

The Sun’s Path

Gomide&Co, through 14 November

As the Bienal de São Paulo opens, the Brazilian city’s commercial galleries are putting on their best clothes. These range Galeria Superficie’s museum-worthy survey of women painting New Figuration in the 1960s and ’70s to a solo show at Luisa Strina for Luisa Matsushita, the artist once known as Lovefoxx from new rave band CSS, but who has recently applied herself to bioconstruction and painting. In their new white cube premises at the top of Avenue Paulista, Gomide&Co takes the opportunity to explore the effect Japanese immigration had on Brazilian art in The Sun’s Path, a well-researched multigenerational group show. In the mid nineteenth century, the abolition of feudalism in Japan left huge numbers of rural workers unemployed, while the end of slavery left Brazil with a massive labour shortage. The outcome is that today São Paulo boasts the biggest Japanese diaspora in the world. Artists such as 94-year-old Flávio-Shiró, as well Manabu Mabe (1924–97) and Massao Okinaka (1913–95) reflected this agricultural history in their sublime and sometimes surrealist landscapes, and it’s a tangent also taken up by contemporary artists present, including Yuli Yamagata with her resin floor sculpture, a vomitous polluted puddle of fake corn husks and plastic flowers. Oliver Basciano

Rayyane Tabet: Arabesque

Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut, through 16 November

When French painter Jean-Léon Gérôme painted the turquoise-coloured tiles inspired by Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace in The Snake Charmer in 1879, he altered parts of the Arabic calligraphy into meaningless doodles to fit the composition. After all, these densely woven patterns were just a piece of visual exotica, an example of the arabesque style, a European concept that encapsulates the ornate styles of the Arab world. Titled after this orientalist genre, Sfeir-Semler Gallery’s opening exhibition at its new Beirut space is displaying Rayyane Tabet’s works, which delve into nineteenth-century scholar Jules Bourgoin and composer Claude Debussy’s arabesque works. In Découpages (1891–2021), Tabet disassembled Bourgoin’s manuscript Precis de l’Art Arabe (1890–92) into individual folios that encircle the gallery walls. Here, Bourgoin’s mechanical drawings of arabesque forms face against the walls while portions of the patterns were cut out and fold outward, leaving a negative space on each sheet that at once suggest absence and removal. In another piece, Tabet drew one letter from the word ‘orientalism’ on each score sheet of Debussy’s Deux Arabesque (1888–91) and generated the melody with certain notes covered by the ink. Thus a resulting incompleteness – of Debussy’s composition and of arabesque as a form – would linger. Yuwen Jiang

newspapers. Photo: Steven Paneccasio. Courtesy MoMA PS1

Jumana Manna: Break, Take, Erase, Tally

Wexner Center of the Arts, Ohio, through 30 December

Land ownership is a contentious issue at the best of times. (Up until earlier this year, I wonder if many people in the UK knew that public rights of way – historical pathways that trail through privately-owned land – had to be registered with local councils in order to be legally protected; now there’s a government-mandated deadline for these paths to be recorded – after that, the public will lose access to the remaining trails. I did not know this and I walk a lot.) But issues such as these seem like relatively small fry when it comes to problems related to the power dynamics of land ownership presented in Jumana Manna’s work. The interdisciplinary artist employs narrative methods (including filmmaking) to ‘visualize the slow violence of industrial agriculture, neoliberal economic policy, and policing. Bearing witness to the ongoing tensions between agrarian histories and state bureaucracies, her practice traces the flows of human and plant life across political and legal boundaries.’ For example, her 2018 film Wild Relatives focuses on the rebuilding of Aleppo’s seed bank, which was forced to relocate during the Syrian war to Lebanon (via the Svalbard Global Seed Vault); last year, she produced a part fiction-part documentary film about the conflicts between Palestinian pickers of wild herbs and the Israeli Nature and Parks Authority, titled Foragers, highlighting the issue of who gets to step where, and the lengths that people will go to in order to maintain their cultural traditions, despite threats of fines and imprisonment. Manna’s exhibition, Break, Take, Erase, Tally was previously shown at MoMA PS1, but now travels to Ohio, where the artist will present nearly 20 works as well as a new installation of sculptures inspired by the remains of khabyas, traditional and now-obsolete structures for grain storage. (Which is fitting, since Ohio is one of the US’s leading states in crop production.) The sculptures promise to ‘echo the grid pattern of the Wexner Center’s architecture, engaging the museum’s role as a site of preservation and control’. Fi Churchman

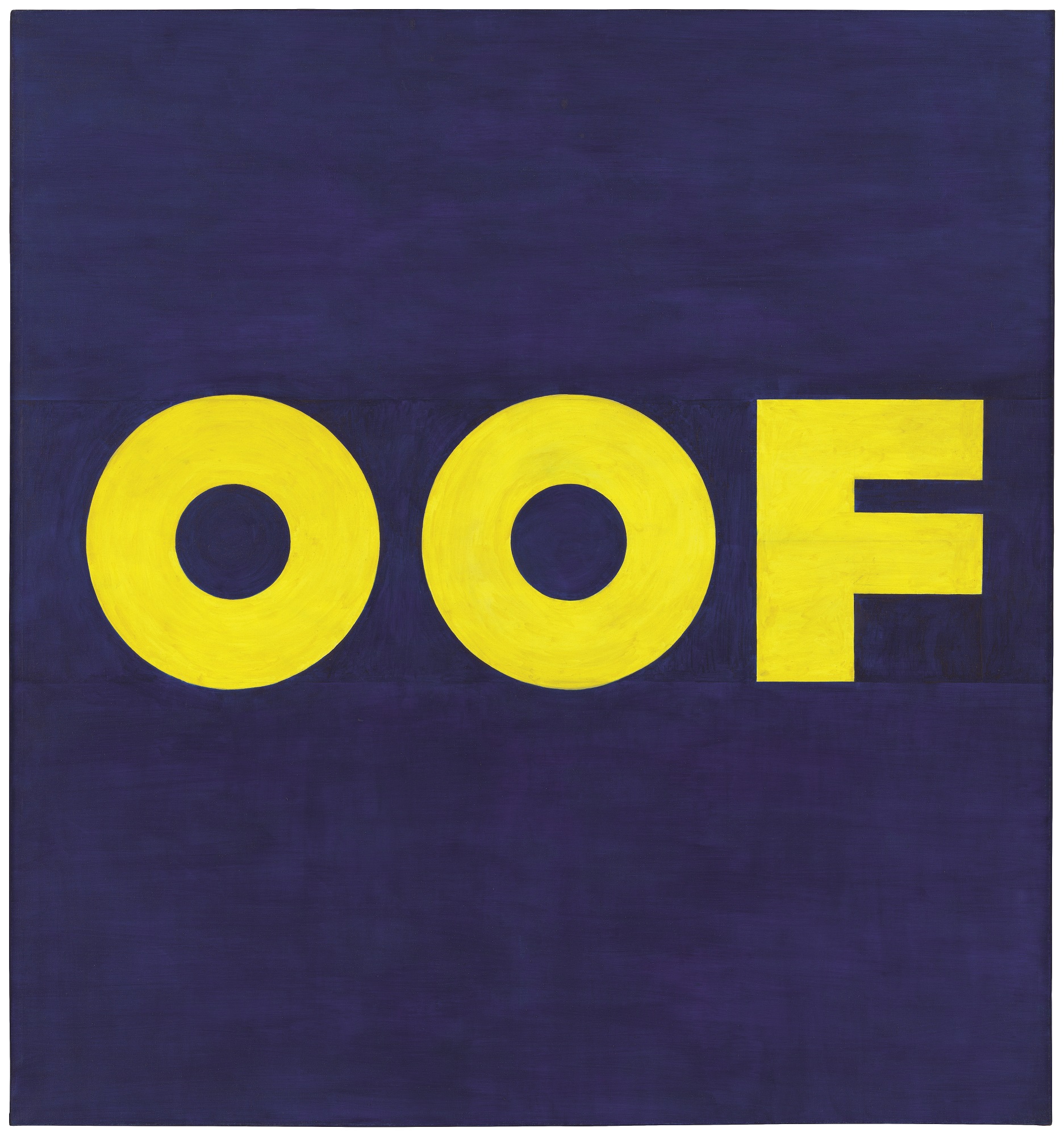

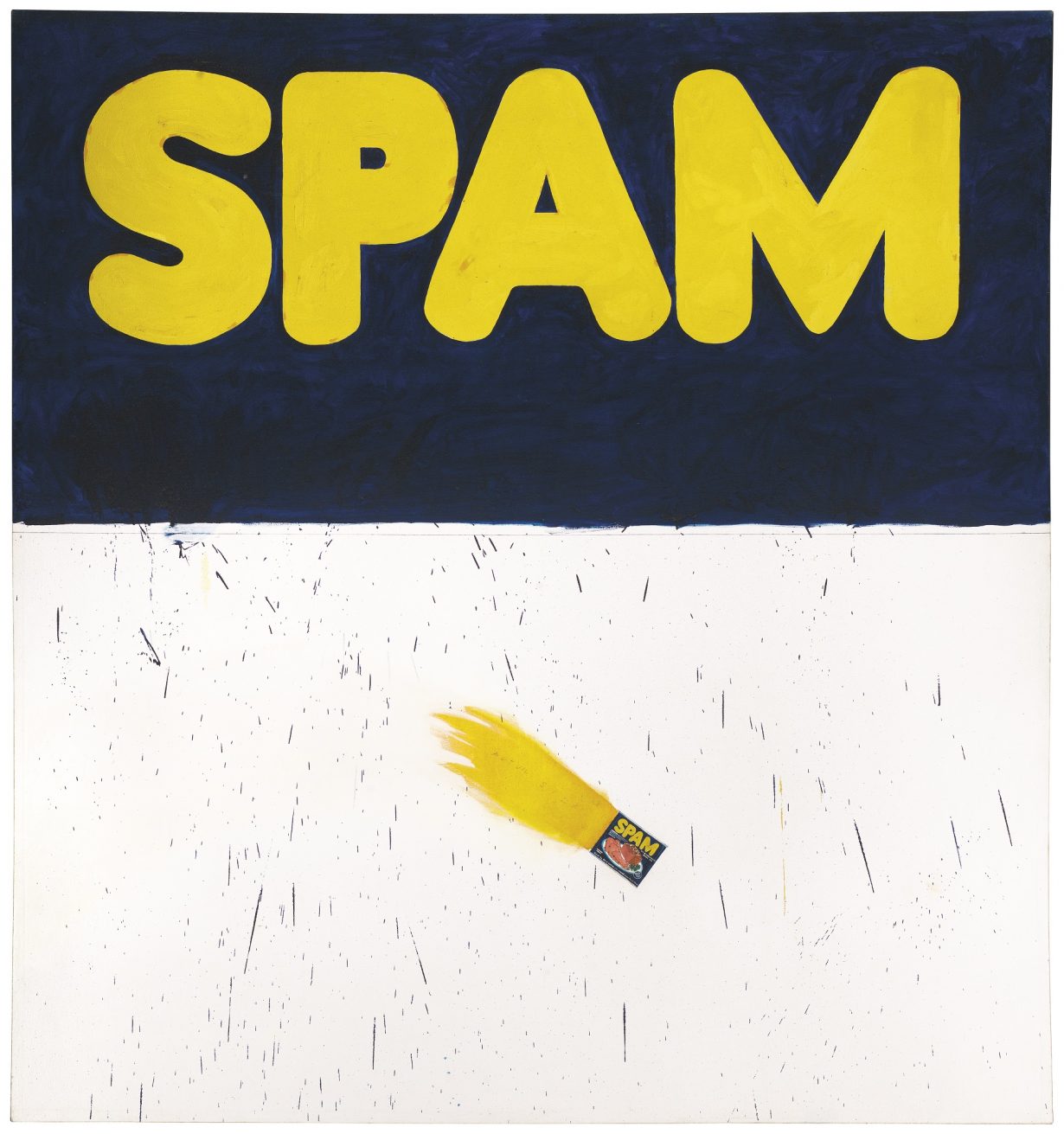

Ed Ruscha: Now Then

MoMA, New York, 10 September – 13 January 2024

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s a tin of flying Spam! The much beloved canned meat rockets across the canvas like a shooting star, yellow flames propelling it from left to right. Along the top of the canvas are graphic yellow letters exclaiming, ‘SPAM’, a contraction for ‘Spiced Ham’, as Ed Ruscha’s painting, Actual Size (1962), pulls at the heart strings of those who still enjoy the convenient source of processed pork protein. OOF (1963), one might think with some trepidation, but it’s a War Surplus (1962), enjoyed across the pacific, perhaps in the form of spam musubi as Hawaiian Music (1974) plays in the background on the Radio (1962). Forgive this Profound Small Talk (1977), but MoMA will be staging the ‘most comprehensive’ retrospective of Ruscha’s work this month (despite the artist once exclaiming, I don’t Want No Retro Spective [1979]). Fear Not (1991), however, there will be more than Words of Wisdom (1986), as the exhibition, Now Then, will also include his famous architectural paintings along with the celebrated artist’s book, Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963). Ruscha has had a profound impact on postwar American art, all with a bit of Jazz (1966) and cheek. Marv Recinto

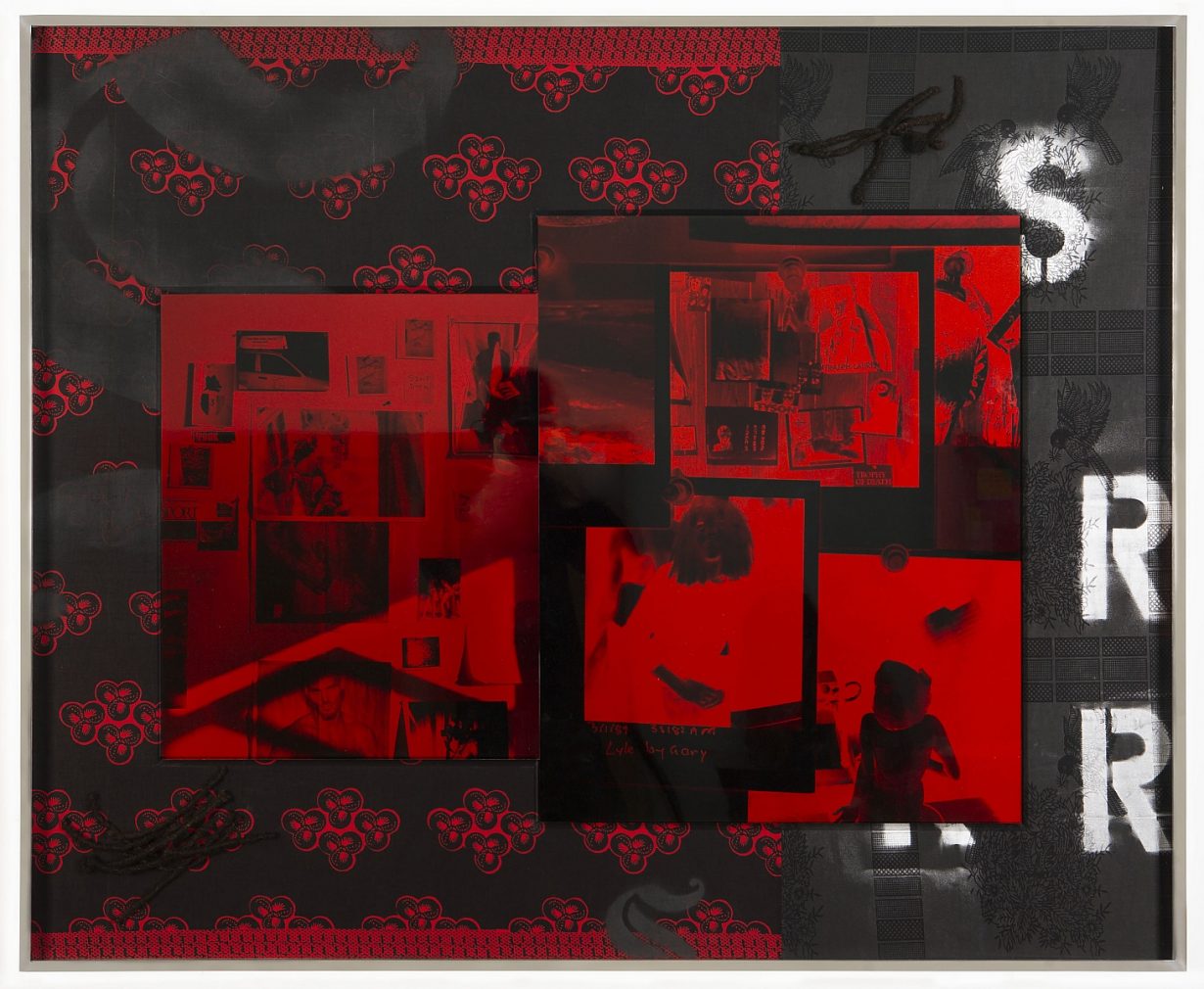

© and courtesy the artist

Tarek Atoui: Waters’ Witness

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 15 September – 4 February

You could say that presenting an exhibition about port cities in an actual port city, at an institution that’s right between a wharf and a quay (and whose neighbour is a certain seashell-shaped opera house), all sounds rather apt. ArtReview Asia supposes it’ll never really know whether or not those locational logistics played a large part in the decision-making process, but that’s where Tarek Atoui will be showing his next iteration of Waters’ Witness (2015–). While the artist and composer’s work generally upends our more traditional ideas of music and musical instruments (for The Reverse Sessions, 2014, for example, the artist invited collaborators to reverse-engineer instruments based on the music he had written and recordings he had made of museum objects that weren’t intended to be played as instruments), Waters’ Witness is his ongoing research project into and documentation of the ‘acoustic identities of port cities’. The findings of which take the form of exhibitions that are part performance, part sound installation. This fascination with ports as sites of movement and global market networks has taken the Lebanese artist from his home city of Beirut to Singapore, Porto, Abu Dhabi, Athens and elsewhere. He makes underwater and coastal recordings of each port in order to create a score that’s specific to the site. These recordings also serve as inspiration for musical devices and sound sculptures (mic’d-up slabs of stone or ceramic vessels, or arrangements of wire coils on tables) – and new, Sydney-specific iterations of these will be on show at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Fi Churchman

In and Out of Time

Gallery 1957, Accra, 16 September – 12 December

Curated by Ghanaian-British writer, editor and curator Ekow Eshun, In and Out of Time draws on the Ghanaian term sankofa, which literally means ‘to retrieve’, more often associated with the proverb ‘It is not wrong to go back for that which you have forgotten.’ In Eshun’s curated exhibition, this idea informs an exhibition about time, the nonlinearity of time, the sense that it’s possible, maybe even necessary, to return to the past in order to move forward. Showcasing the works of artists including Lyle Ashton Harris, Zanele Muholi, Emma Prempeh and Tiffanie Delune, the exhibition brings together artists working across mediums and geographies to interrogate concepts of time, African diasporic identities and collective memory. In and Out of Time runs parallel to a solo show by Yaw Owusu, curated by Nigerian curator Azu Nwagbogu, as well as A Thousand Disguises, an exhibition of works by Priscilla Kennedy, who won the gallery’s Yaa Asantewaa Art Prize 2022, given annually to a Ghanaian woman artist. Orit Gat

Leelee Chan

Capsule, Shanghai, 16 September – 28 October

Leelee Chan’s sculptures always look a bit like objects that have been dropped by extraterrestrials onto Earth. To be fair, her plastic gridlike, wall-hung sculptures are called things like Cipher (Surface Modular) (2022) and Nocturnal Encounter (2021). So it’s not a giant leap of the imagination. The 2020 BMW Art Journey winner typically makes these out of found plastic pallets, which she cuts into circles, ovals, squares, etc, filling gaps with materials like resin, metals, acrylic and semi precious stones, so that they end up looking like an important part has fallen out of a spacecaft, or some kind of celestial timekeeper, or an intergalactic wayfinding device based on Micronesian stick charts or… There’s combined fragments of Ming dynasty ceramics with metal hardware, woods, plastics and resin; the collective result looking like a diorama of artefacts that ETs might use to educate their offspring about the human species. At Capsule, Chan presents new, larger works, including the freestanding oval-shaped sculpture Lithic Current (2023), which incorporates parts of shipping pallets and looks like it might be an ancient relic of an alien energy generator. Or is it a prehistoric time portal? Spacing out is half the fun. Fi Churchman

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy: Filling Station

The Kitchen at Westbeth, 16 September – 3 November

Filling Station is a reinterpretation of a 1938 one-act ballet of the same name by Lincoln Kirstein and George Balanchine based on a news story about one fateful night in a gas station attendant’s life. The original performance is recognised as the first ballet directed by an American choreographer, danced by an American company, and based on an American theme, with music and designs by American artists and is reimagined by Lutz-Kinoy with new choreography, music and set design to make a contemporary version that creates queered space for a reflection on race, class and gender. Filling Station will be performed three times: twice in a gas station on Horatio Street in the West Village and once at Dia:Beacon. After the performances, there will be an exhibition of new paintings by Lutz-Kinoy, as well as archival materials, audiovisual elements and ephemera at the Kitchen’s temporary space, a loft in the famous Westbeth Artists Community, a nonprofit founded in 1970 in New York City to provide affordable housing for artists and their families. Orit Gat

In Excess

Gajah Gallery, Singapore, 21 September – 22 October

Excess isn’t all bad. Sure, we shouldn’t take in excess, produce in excess or, some might argue, live a life of excess. In Excess, a group exhibition of works by artists from the Philippines, however, suggests that perhaps there’s a time and place to revel in it. For almost 350 years, the country was thought of as ‘excess’ – secondary, disposable – by its various colonial rulers, yet part of its present independence is an ongoing effort at decolonialising and rethinking the terms of that legacy. The 11 artists–including painters Marina Cruz and Charlie Co, as well as multimedia artists Imelda Cajipe-Endaya and Leslie de Chavez – on show here seek to demonstrate excess’s potential, reinterpreting and reframing it to appreciate or expand upon its surplus nature. After all, its verb form is ‘to exceed’, which to one strand of thought might imply a positive way of thinking: imagining beyond what already is. Marv Recinto

Tania Perez Cordova: Generalization

SculptureCenter, New York, 23 September – 11 December

The first survey exhibition of the Mexico City–based artist in a United States institution, Generalization presents Pérez Córdova’s conceptual and poetic process. For the first iteration of this exhibition at Museo Tamayo in the artist’s hometown, she had removed the museum’s windows and bent them using heat, transforming them into sculptures (there is also a series of window sculptures made with the windows from her studio). It’s an example of how Pérez Córdova’s work often embarks from an object in the world – a chandelier, a set of contact lenses – that the artist appropriates and transforms. The contact lenses are separated: one is worn by a performer who sometimes wanders the exhibition, looking visitors in the eye; the other is incorporated into a sculpture. The chandelier? It’s recast using a mould of its former self, rendering it anew, also a shadow of itself. Time-based and narrative, Pérez Córdova’s works offer a new form of encounter. Orit Gat