From 2016: ‘Artivism’, in which art and activism combine to question and disrupt existing structures, is often by its nature temporary and collective, resulting in a form that is difficult to categorise, situate or give a value to. Does this make it more effective – or less?

‘Ambiguous images had led to the forgetting of Being, and to the belief that a shift in imagination effected actual changes of Being,’ criticised Carl Einstein after he himself had supplied, more than 15 years earlier, the theoretical foundation for Cubism in his legendary 1915 monograph, Negro Sculpture. With these words, republished in his posthumous 1973 volume Die Fabrikation der Fiktionen (The Fabrication of Fictions), Einstein became one of the first to advocate forcefully for activist art – art that would go beyond the mere production of aesthetic images and sculptures and explicitly strive for ‘actual changes of Being’. Still today, however, ‘artivism’ goes largely ignored by the art establishment: although a modest number of exhibitions may feature it, galleries ignore its existence and the big art journals tend not to address it. In light of the status quo of activism, artist/writer/activist Gregory Sholette, borrowing from theoretical physics, chose the term ‘dark matter’ – describing a state in which something is evidently present but not visible – as the title for his 2006 book on activist art since the 1920s. Sholette clarifies that activist art over almost the last hundred years, but especially since the 1960s – globally yet for the most part outside the art establishment – was exceedingly engaged and politically relevant, and didn’t content itself with the creation of ‘autonomous’, ie purposeless and self-contained works produced by only one artist. As opposed to art that is easily exhibited and sold, the focus here is on temporary and collective actions and processes that seldom find a way into the canon of bourgeois art history. This form of artistic work promises neither cultural nor commercial value; rather, it intervenes critically and discordantly in sociopolitical and economic structures. Protest, not profit; and, needless to say, this is problematic for our now fully commercialised system of art.

Take, for instance, the activist artworks created by the New York collective Guerrilla Art Action Group (GAAG), which, during the late 1960s, provided the blueprint for the artivist actions we know today, such as those by the groups Occupy Museums and Gulf Labor in the US, Russia’s Pussy Riot and Germany’s Zentrum für Politische Schönheit (ZPS, Center for Political Beauty). GAAG was founded by Jon Hendricks and Jean Toche and carried on until voluntarily disbanding in 1976. On 18 November 1969, four of its members gathered in the lobby of New York’s Museum of Modern Art and appeared to slit their stomachs with knives. Red blood poured from packets hidden beneath the activists’ clothing as they ‘expired’ at the no-longer-pure high altar of art. Beforehand they had distributed flyers throughout the museum demanding the resignation of the Rockefeller family from the board of MoMA, on account of its attitude towards the arms industry and the Vietnam War. One year later, also at MoMA, and with heavy symbolism, the group laid a funeral wreath before Picasso’s legendary antiwar painting Guernica (1937). As hybrids of performance and political demonstration, both actions are typical examples of GAAG’s artivist work, which also included the writing of manifestos, such as those on the precariousness of being either a female or black artist. Taken together, they constitute an attempt to deconstruct the allegedly apolitical yet, in fact, hegemonic character of art museums, with the intention of exposing how these cultural institutions again and again provide space for consensus-driven art and recreational fun for a lucky few while acting as profitable money launderers and foci for financial investment.

Occupy Museums, the artist collective that grew out of Occupy Wall Street in 2011, carries on the work of GAAG by also targeting the institution of the museum. In the words of its initiating member, Noah Fischer (writing in the Fall 2015 issue of the online journal Field), the ‘global network connecting museums, auctions, art fairs, and biennales functions as an informal networking channel for a global capitalist class while the image of this luxurious lifestyle and high production aesthetics are dang led before the noses of the 99% as the ultimate sign of aspiration’. The group focuses more and more on criticising this highly asocial quality of museums, which, in many institutions, also manifests itself in the precarious working conditions for their supposedly less-qualified employees. In 2012 the group’s actions included camping for several months at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art during the 7th Berlin Biennale. At KW, one of Berlin’s primary stations on the postmodern art pilgrimage, where more-or-less hip art is discussed and undergoes a subsequent upvaluation on the art market, the group organised a programme that was purely discursive in nature – speeches, discussions, workshops – yet managed to initiate aggressive artivist actions like the ‘raid’ of a Deutsche Bank affiliate in the style of anarchist street theatre.

During the 2015 Venice Biennale, Occupy Museums teamed with Gulf Labor in occupying the Peggy Guggenheim Collection for several hours, an action that received enormous media attention. The idea was to raise critical consciousness of the inhumane working conditions under which Guggenheim Abu Dhabi is currently being constructed in the United Arab Emirates. Another dimension to these activities in this context is the 2015 publication of the book The Gulf: High Culture / Hard Labor. In light of the work by Occupy Museums and Gulf Labor, which is highly critical of the system and has been introduced here only briefly, it is thus beyond comprehension that Claire Bishop, in her essay ‘Black Box, White Cube, Public Space’ (2016, published on Skulptur Projekte Münster’s website), used thoroughly ignorant argumentation to describe artivism as affirmative and neoliberal: ‘After Occupy Wall Street in 2011, performance has migrated into the safety of the museum, rather than take place on the streets. In tune with neoliberal politics, this work tends to be organized around consent rather than dissent.’

Today, other artivists are no longer locating their political artistic work in the context of institutional criticism, but instead are deliberately positioning themselves outside the art establishment, as did the Dutch visual artist Jonas Staal with his participatory project New World Summit (2015–16). Since 2012 he has organised alternative parliamentary forums that convene in various locations across the world to debate, from various perspectives, the status quo of ‘our’ democracies. For instance, the ‘Terrorism Congresses’ address, in part, provocative questions that can be simplified as: what is terrorism and who is actually a terrorist? Neither question is as straight forward as it may perhaps seem at first; the official lists of sought-after ‘terrorists’ in Germany differ significantly from those in France and the US, and each country’s definition of ‘terrorist’ stems not from ‘ objective’ circumstances, but from variously configured power relationships.

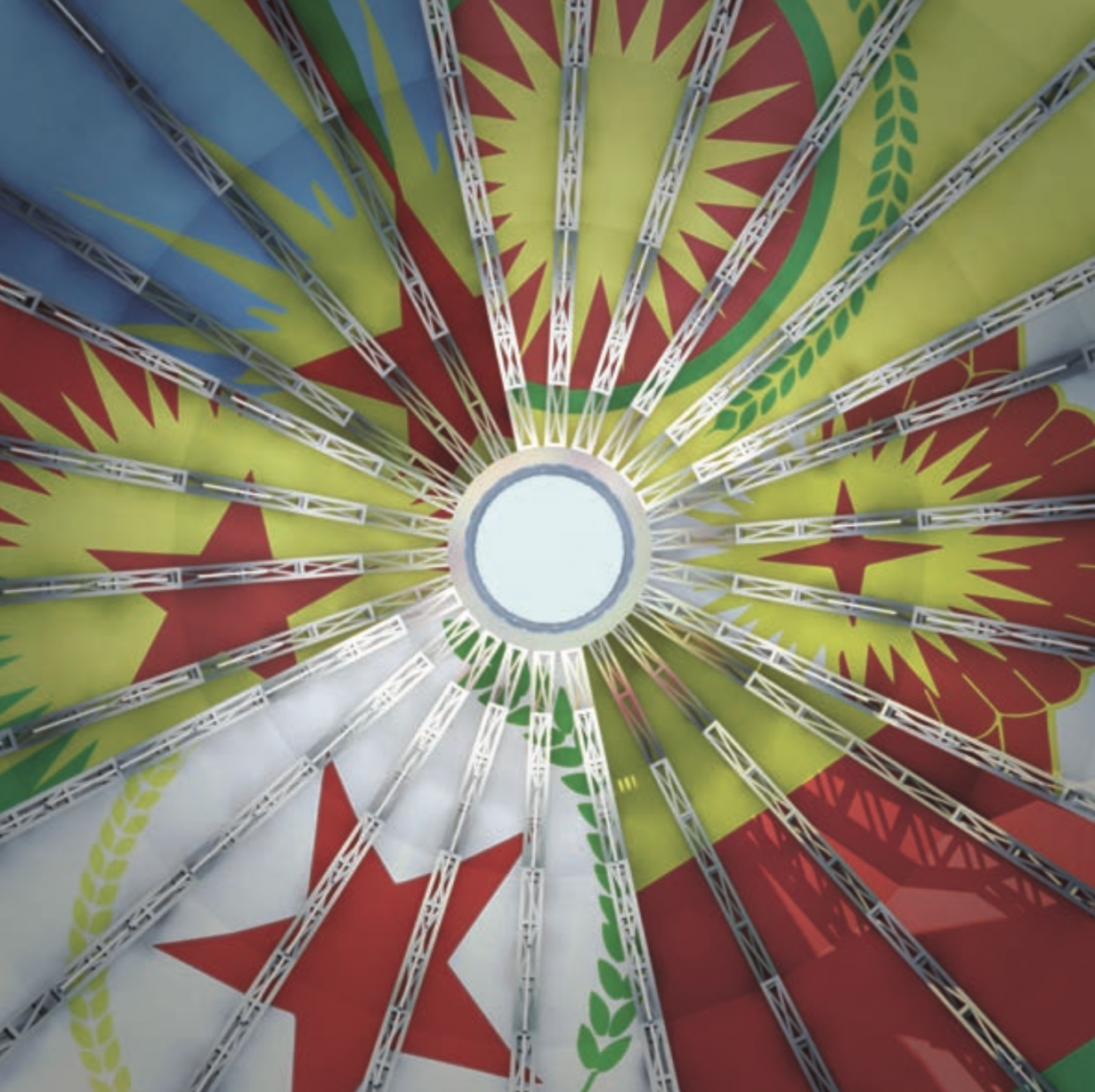

Most recently Staal erected a ‘parliament building’ in the autonomous Kurdish region of Rojava, in northern Syria, where he organised a conference on ‘stateless democracy’. The autonomous region served as a sort of concrete, ideal case for a concept of democracy that, among other things, shows that it ‘is no longer demographically limited’ (Staal). The participants invited to such forums of the New World Summit include representatives from autonomous civil-rights movements , ‘terrorists’ (ie people on the terrorist list), political scientists, lawyers and journalists . In an artistically structured setting – replete with specially designed flags – the conference members heatedly debate a differentiated set of topics for days, focusing (to paraphrase political theorist Chantal Mouffe) on a conflict-filled depiction of the globalised world. These debates, which are seldom staged without a fair share of controversy, leave the participants quite obviously at loggerheads with actual neoliberal policy.

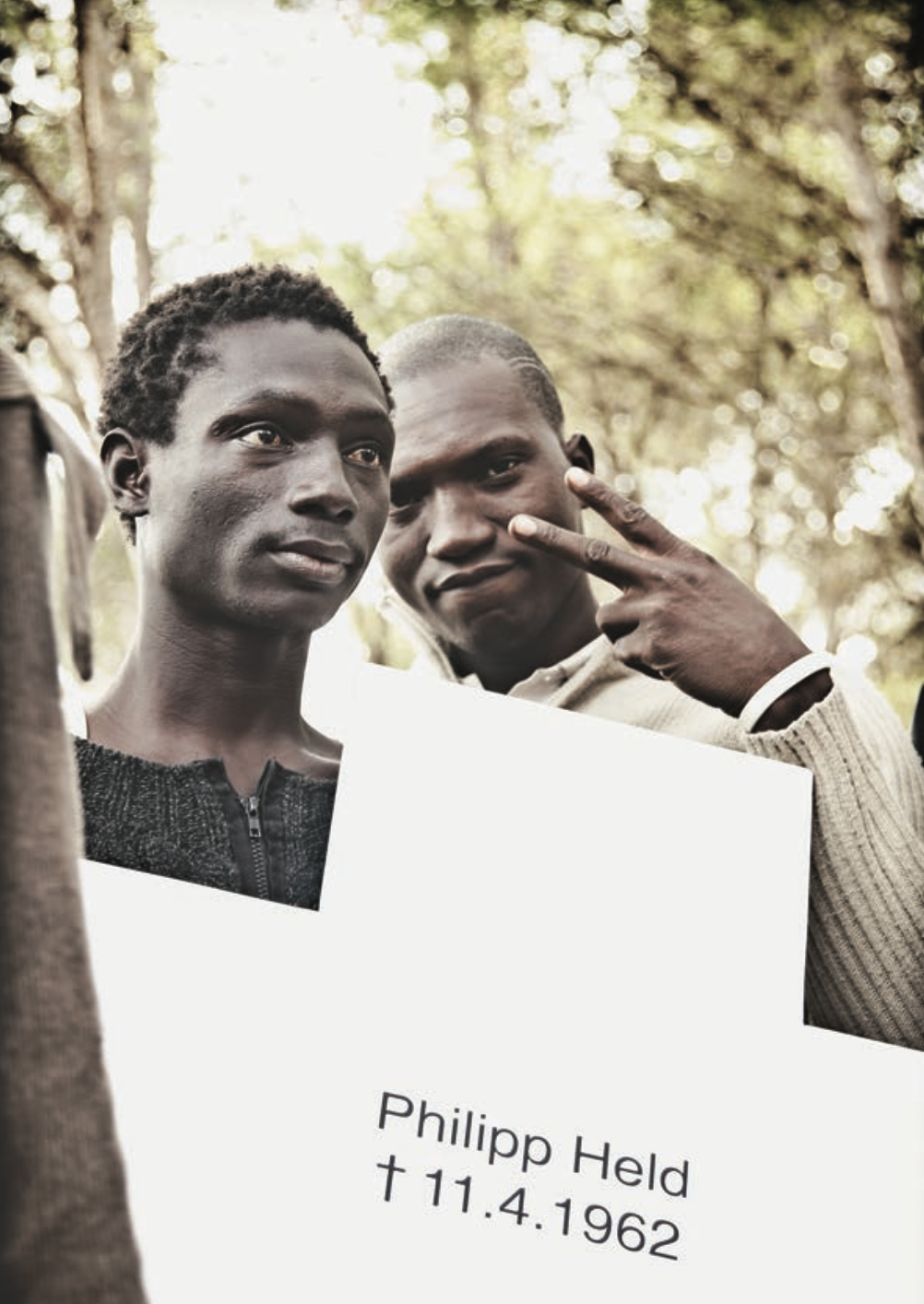

The artistic work of the ZPS collective in Germany also refutes Bishop’s polemical assertions that activist performances in the safe, politics-free space of a museum are in retreat in order to be ‘in tune with neoliberal politics’. The group’s action Erster Europäischer Mauerfall (First Fall of the European Wall, 2015) is a prime example. Precisely as official Germany was readying itself to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, ZPS removed 14 Wall crosses – which had been installed in honour of those killed along the Wall during the Cold War – and repositioned them at various locations along the external border of the EU. On the group’s website, photos were posted of white crosses and dark-skinned refugees behind barbed-wire fences, some at border installations in Bulgaria and Greece. The campaign set out to highlight the refugee situation at the borders of Europe, where the First World is building new walls to keep out the misery that is so pervasive beyond its sphere of influence. After all, since 2000 close to 30,000 people trying to reach Europe have died, a good portion of them in the Mediterranean Sea.

In an interview, ZPS spokesman Philipp Ruch explained this symbolic action involving the 14 Berlin Wall crosses: ‘The “white crosses” collectively left the city’s government quarters to escape the commemoration festivities… In an act of solidarity, the victims fled to their brothers and sisters across the European Union’s external borders, more precisely, to the future victims of the wall.’ Of course, the media response to this aggressive action was immense, and legal consequences loomed. The ultimate effect, however, was the collective’s success at presenting and discussing an urgent political problem before a broad public, and – much like the actions by Jonas Staal – doing so without accepting and affirming the omissions and politically correct pleasantries that seem to be prescribed for such discussions. Not least through this sort of ‘aggressive humanism’, as Ruch termed it, today’s activist art is seeking to expedite – to quote Carl Einstein again – ‘actual changes of Being’.

Translated from the German by Jonathan Lutes. This article was first published in ArtReview September 2016