The decision of the BBC to restore a statue created by Eric Gill without consulting with victims of abuse reveals an institution unable to reckon with its own dark past

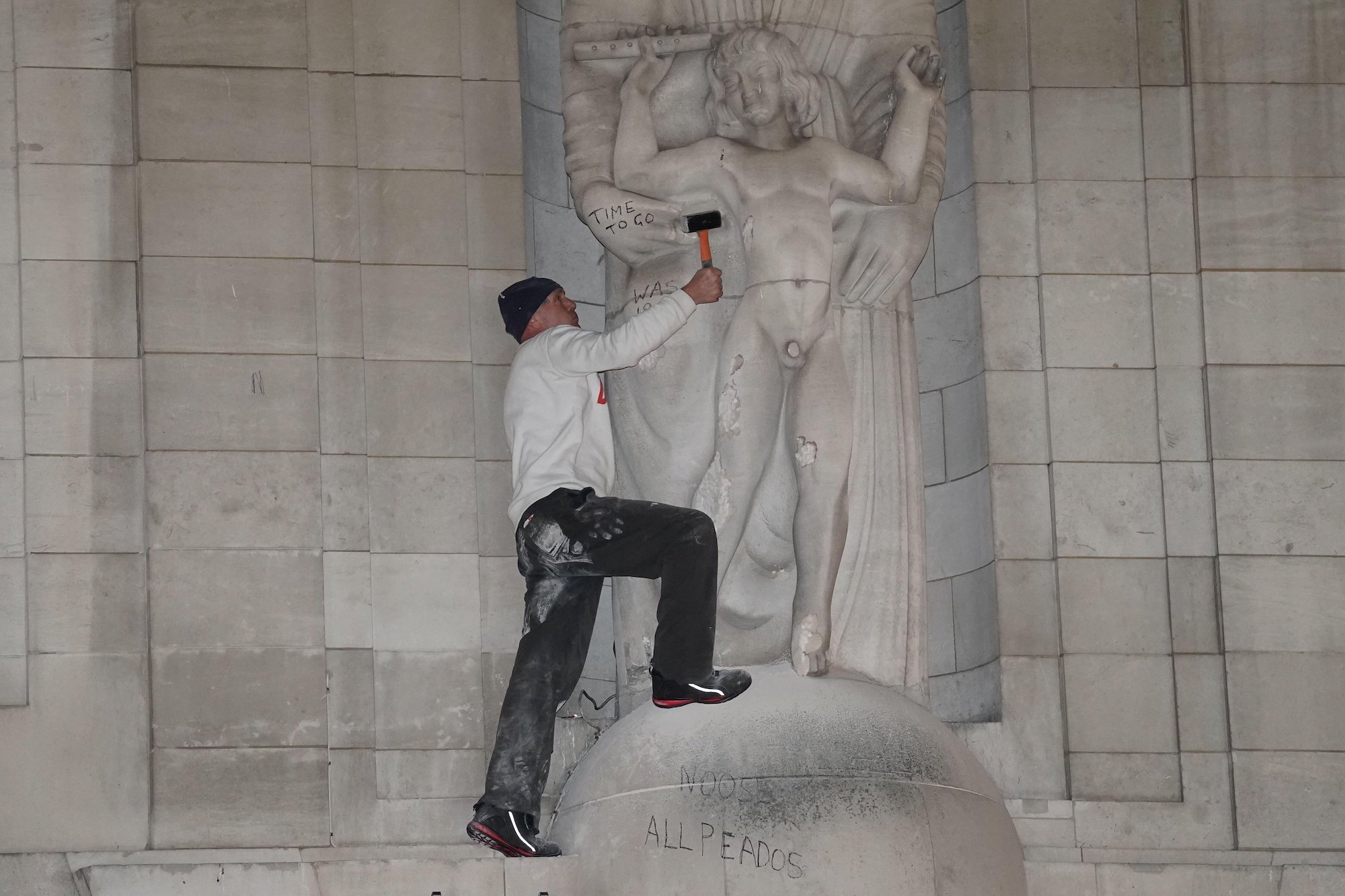

On an overcast Wednesday afternoon in January 2022, a 54-year-old man ascended a ladder at Broadcasting House in central London to the ledge where Eric Gill’s 1932 statue of Prospero and Arial from Shakespeare’s The Tempest stands. As a companion guarded the ladder, filming events on his phone, the protester chiseled the foot of the statue and daubed graffiti on the 10-foot figure: ‘BBC PAEDOS + PROPAGANDA’; ‘TIME TO GO WAS 1989’; ‘NOOSE ALL PAEDOS’. It took about four hours for the Metropolitan Police and the London Fire Brigade to bring the protester to safety before detaining him.

Across the last decade, as scandals around historic child abuse at the BBC have come to light, this statue has become a lightning rod for both child abuse victim groups and, more recently, right-wing agitators after its sculptor was posthumously revealed to have molested his teenage daughters. In right-wing Facebook pages and forum posts, the statue is seen as a public symbol of either the corporation’s culpability over child sexual abuse, or of its active engagement in a wider and darker QANON style abuse conspiracy. This week, the BBC announced that it will begin repair work on the statue, funded by insurance payments rather than licence fee contributions. The corporation said that it took advice from Historic England, and that the statue will now be accompanied by a QR code providing smartphone users with instantly available context on Gill’s crimes.

The furore feels emblematic of the limits of public discourse around child sexual abuse. Seemingly everybody gets a say – the BBC, far-right activists, broadsheet columnists – but not victims, nor those groups that represent and support them. Is there a way to respond meaningfully to art that has become complicated by issues around child sexual abuse? Can the voices of victims ever be usefully assimilated into the presentation of a work of art?

Arthur Eric Gill (1882-1940) was an English sculptor, typeface designer, printmaker and writer. While he initially identified with the Arts and Crafts Movement he later rejected it in favour of a form of utopian Roman Catholicism. The charismatic, self-styled radical artist established craft communities in his own image and likeness, most notably at the Ditchling site in Sussex which today houses the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, home to the UK’s largest Gill collection. Eric Gill’s art had an outsized influence on the visual language of British public life. There are dozens of memorials across England designed by Gill commemorating the First World War dead. Gill’s work can be found in commercial spaces (his brilliant design at Morecambe’s art deco Midland Hotel), in places of worship (his 1913 Stations of the Cross at Westminster Cathedral), and in hallowed educational sites (Gill’s work features in seven Oxford colleges). His typeface, Gill Sans, would become the font of choice for signage, posters and timetables across the UK’s railway network.

When cultural historian Fiona MacCarthy began working on a biography of Gill during the Thatcher years, few could have anticipated that the resulting 1989 book would continue to have repercussions decades after its publication. Using Gill’s own personal diaries and writings, MacArthur was able to evidence for the first time the artist’s extensive history of abuse. Gill sexually abused his two eldest daughters and had incestuous sexual relationships with two of his sisters. ‘His sexual obsessiveness he rationalised into seeing sex as an aspect of God’s glory’, wrote MacArthur, of a man who conducted scores of extramarital affairs and molested the family dog.

At the very birth of Broadcasting House, there was Gill. In April 1932, as hundreds of vans loaded up 300 tonnes of equipment and paperwork, Gill posed for photographs as he completed work on his sculpture, clad in a beret, large smock and hobnailed boots. From its genesis, the Prospero and Ariel sculpture was controversial. MacCarthy reported that the BBC governors, given a preview of the carving behind tarpaulin, asked whether the artist could make the genitalia of the Ariel figure more diminutive. A question was tabled in the House of Commons on the same issue.

Ninety years on, the debate continues. JJ Charlesworth wrote last year for ArtReview that Gills’s acts, not his art, were his crimes. ‘His works are part of a larger art-historical movement and moment, and they have content, form and style that have nothing to do with Gill’s perverted personal life’. This was echoed by veteran art critic Jonathan Jones, defending the BBC’s decision in The Guardian this week, who argued that restoring the statue is ‘the only moral thing the BBC can do’, citing the statue as integral to the ‘history and fabric of a noble building’. But more so than perhaps any other twentieth century building in Britain, it is the ‘history and fabric’ of Broadcasting House that has been called into question across the last decade, as historic and institutionalised child sexual abuse was uncovered at the corporation. Speaking anonymously to Andrew O’Hagan for the London Review of Books, a former BBC employee discussed their experiences at Portland Place during the 1950s: ‘Broadcasting House was well stocked with men interested in sleeping with young boys,’ said the employee, ‘it was a milieu back then.’ Reflecting on his interviews with those who worked at the corporation in the 1950s, O’Hagan noted simply, ‘they speak like survivors’.

This institutional culture preceded Jimmy Savile’s arrival at the corporation. Through the 2016 Dame Janet Smith Review and the landmark 2014 biography In Plain Sight by Dan Davies, we now understand the corporate structure that was built around Savile and his seemingly untouchable success. This endured from the 1960s to his 2011 death. After his passing, as Britain woke up to the industrial scale of Savile’s criminality, sexual abuse charities called for the Prospero and Aerial statue to be removed. Fay Maxted, the chief executive of The Survivors’s Trust, said that it was an ‘insult to allow a work like this to remain in such a public place’. Peter Saunders, chief executive of the National Association For People Abused In Childhood, posited that there was a ‘strong argument that this should be removed. These symbols are in people’s faces’. When the BBC declined, they cited Gill’s record as ‘one of the last century’s major British artists whose work has been widely displayed in leading UK museums and galleries’. Though true in 2013, this is no longer reflective of Gill’s standing.

Beginning in 2017, the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft have refocused their work towards foregrounding Gill’s abuse. For their 2017 exhibition Eric Gill: The Body, curators talked to groups who work with those that have experienced sexual abuse. Staff and volunteers received extra training ahead of that exhibition. Then last year, the museum began repurposing itself away from Gill’s work altogether. For ten months in 2022, for the first time in its history, none of Gill’s works were shown at the site.

The response of galleries and institutions to their troubled relationship with Britain’s colonial past offers some insights that can be applied to Eric Gill’s work. Some offer a blueprint in how to move beyond enforced binaries around complicated art that make claims for either complete removal of pieces or enforced amnesia. Manchester Museum, in dealing with objects linked to colonialism in its collection, have repatriated some objects and appointed a curator to reassess others from an anticolonial perspective. The National Gallery is highlighting individuals hung on their walls who were linked to slavery, while Tate Britain is taking paintings linked to the British Empire out of dusty storage and displaying them with labels explaining, in clear terms, their links to racism and the slave trade. One year after the statue of transatlantic slave owner Edward Colston was toppled, defaced and pushed into the Bristol Harbour in June 2020 during protests against the murder of George Floyd, it was displayed horizontally in its defaced form at Bristol’s M Shed museum. Some of the demonstration placards, now recognised as part of history themselves, were exhibited nearby.

Institutionalised child sexual abuse is also a factor of British history that demands to be reckoned with. With the public debate over the statues of Eric Gill, the BBC has found itself in a position where it is uniquely placed to engage on these issues. And because of its specific history and failings around child abuse, it has a particular responsibility to do so. The decision to use the mute symbol of a QR code for context is tokenistic and operating at the shallow end of the bare minimum. The BBC is hoping that the restoration of Prospero and Ariel will close the matter, that it can move on quietly and without fuss. Instead, the corporation must meet with survivors’ groups, and make this the beginning.