Putin’s Russia barely goes a day without some new punitive measure

To seek new or interesting ways to explain the decade-long erosion of independent free speech, expression or culture in Russia has become a repetitive and tiresome task. Under Putin, the country barely goes a day without the announcement of some new punitive, oppressive measure. But perhaps it has reached a highpoint of international interest now that all such measures are shrouded by the ongoing detention of activist and opposition figurehead Alexei Navalny, who was transferred to a prison hospital earlier in April and whose health is on a continuous downwards spiral.

But then there’s the case of Yulia Tsvetkova – the twenty-seven-year-old feminist and LGBTQ+ artist currently on trial in Russia, facing the possibility of a six-year prison sentence for ‘creating and distributing pornographic materials’ under Article 242 of Russia’s Criminal Code. There are fewer international headlines related to that.

Her trial, in the small city of Komsomolsk-on-Amur, around 1,000km north of Vladivostok in Russia’s far east, is as unsophisticated as her somewhat twee, primitivist art. Moreoever, it has been closed to the public since 12 April – to protect them from the ‘pornographic images’ that are being displayed as ‘evidence’. Tsvetkova’s family believes there is a different motivation.

“The court closed sessions, so that they wouldn’t be written about, and journalists wouldn’t go to court,” Tsvetkova’s mother, Anna Khodyreva, told me. “The human rights ombudsman wasn’t allowed in, the public defender was not allowed in. Two prosecutors are sitting in court, this happens very rarely,” she added. “Now for almost a year even local bloggers have not written about Yulia’s case.” Yulia herself cannot discuss it, she added.

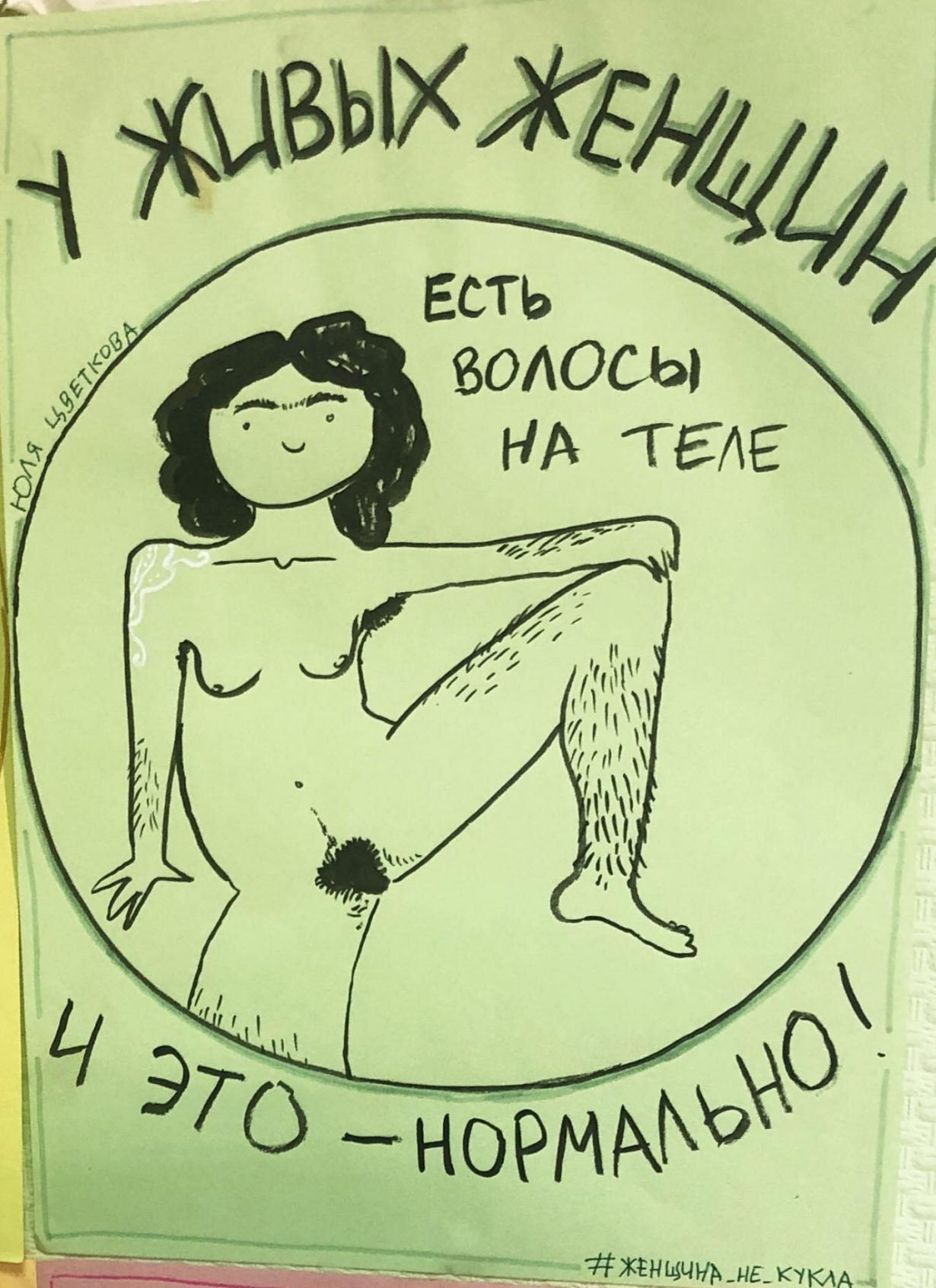

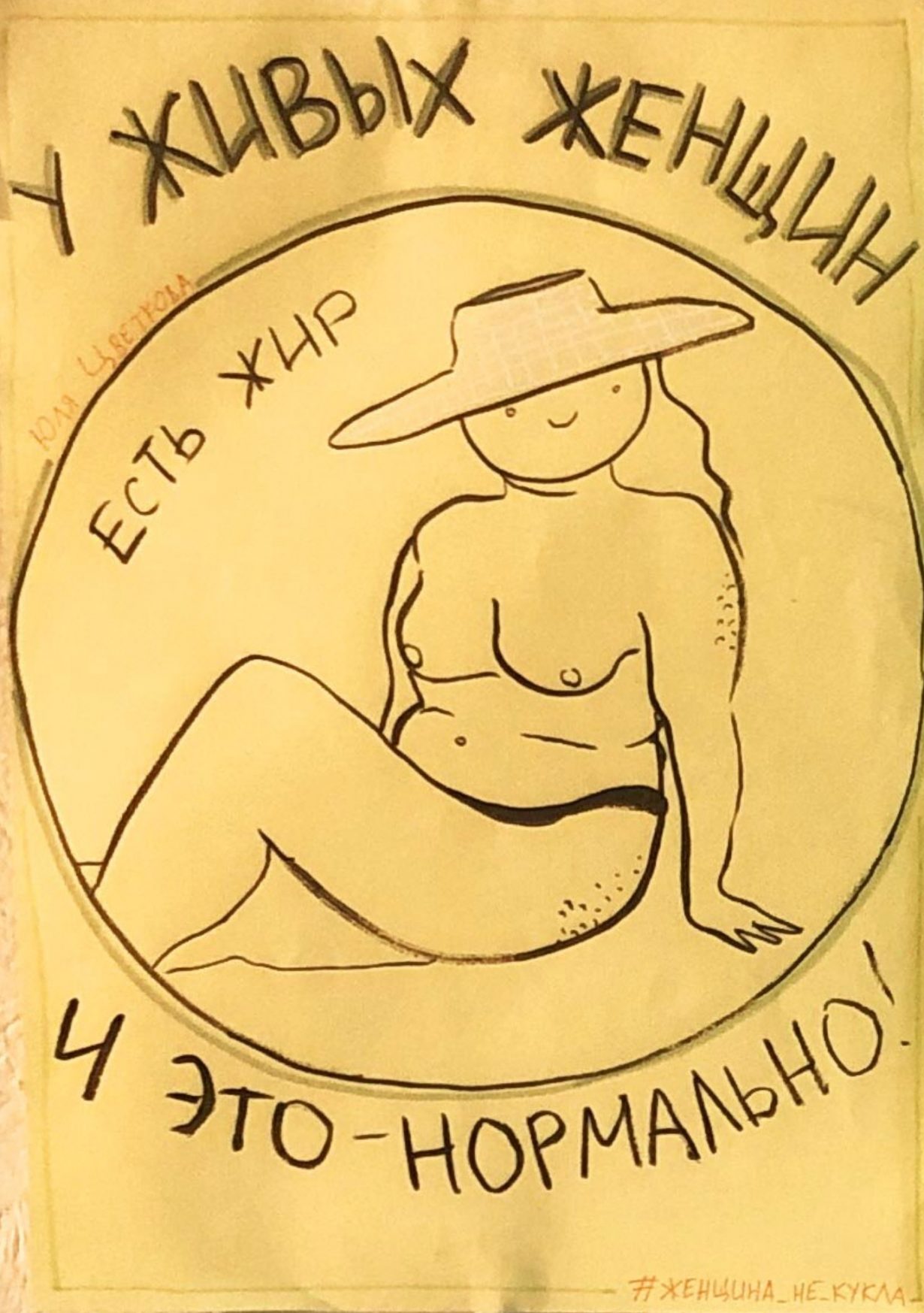

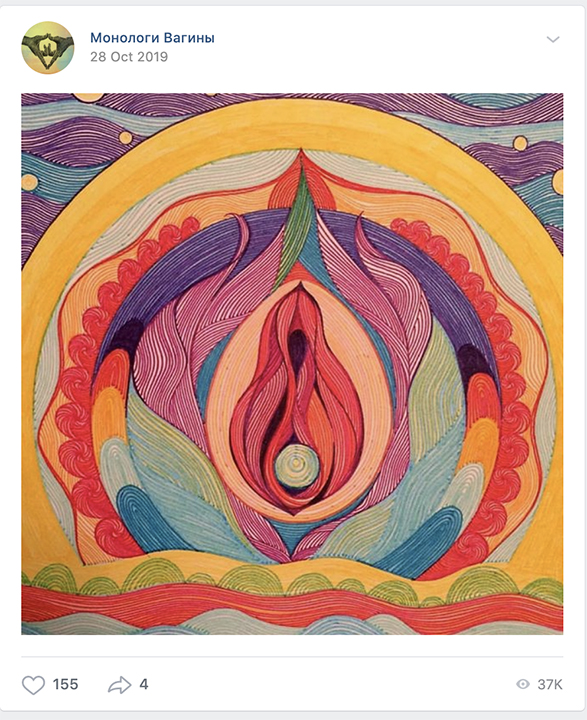

The artworks in question – a series titled ‘A Woman is not a Doll’, first produced in 2018 – are simple line-drawn cartoons: naked women show their body hair, tampons, or stretch marks, accompanied by various innocent observations that women have body hair ‘and that’s normal’, or that women have body fat, or acne, or grey hair ‘and that’s normal’. The VKontakte (Russia’s Facebook) group that she presides over, and through which she allegedly ‘distributed pornographic materials’, hosts a wide variety of far more explicit prints: from labia rendered in watercolour to elaborate embroidered vulvas.

The trial, of course, is about so much more than just drawings. It has ignited criticism from Russian artists, feminists, and human rights organisations alike. ‘A woman has been criminally charged with ‘producing pornography’ simply for drawing and publishing images of the female body and freely expressing her views through art,’ said Natalia Zviagina, Amnesty International’s Moscow Office Director. ‘During this ordeal, Yulia has spent time under house arrest and twice been subjected to extortionate fines under the so-called “gay propaganda” law.’

Russian human-rights group, Memorial, commented specifically on Tsvetkova’s drawings’ non-sexual nature. ‘The materials used to incriminate Tsvetkova, in principle, cannot be recognized as pornographic,’ the organisation said. They ‘have a certain artistic and ideological value […] these materials are no more pornography than images of genitals in a school anatomy textbook.’

“It is sad when women say that the vagina is shameful, or not beautiful, or terrible,” said Khodyreva. “Vagina, this is just the name of a part of the body.”

Since Tsvetkova was first persecuted by the Russian state (she was initially summoned for questioning in early 2019), a swathe of feminist artists and activists have come to her aid – most notably Daria Apakhonchich, who staged a supportive ‘Vulva Ballet’ outside the iconic Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg last summer. Participants, dressed in crimson, held up narrow, rosy renditions of vaginas while dancing in similarly-shaped hats. The results were both beautiful and hilarious – but not to the eyes of the Russian branch of the Red Cross for which she worked. It informed her that she might be let go, ostensibly on account of the pandemic.

“They told me by phone that now [due to the pandemic] the rules for working with children are changing and, perhaps, they might not get me back to work,” Apakhonchich told me shortly after her performance last year. The apparently charitable nature of the Red Cross in Russia made her confused about its principles. “These matters are very important to me: women’s solidarity is very important to me, because we have nothing but her: no protective laws, no resources, no culture,” said Apakhonchich. “The word ‘vulva’ has become a trigger”.

Apakhonchich was placed on a ‘foreign agent’ media register at the end of last year, meaning that she now has to preface any video or story she publishes online with the statement: ‘THIS MESSAGE (MATERIAL) HAS BEEN CREATED AND (OR) DISSEMINATED BY A FOREIGN MASS MEDIA OUTLET PERFORMING THE FUNCTIONS OF A FOREIGN AGENT, AND (OR) A RUSSIAN LEGAL ENTITY, PERFORMING THE FUNCTIONS OF A FOREIGN AGENT.’

Victoria Lomasko, author of the graphic novel Other Russias (2017), expressed similar concerns about her employment prospects in Russia as a feminist artist. “These situations demonstrate an overwhelming level of violence and censorship in Russia,” she told me. “But this is not news, but a long-known sad fact.”

“Since 2014 I have not had any job in Russia because of my political views and art,” she added. “These situations demonstrate an overwhelming level of violence and censorship in Russia.”

Artist and feminist writer Galina Rymbu also penned her powerful poem, ‘My Vagina’ last year in support of Tsvetkova. In it, she observes: ‘I lived in а world of assigned reading / where everything is viewed through the male gaze / in the world of streetgangs and stairwells full of sweaty / guys in black jackets and tattered boots’.

‘Everyone had an interest in my vagina: the state, my parents, gynecologists, strange men […] I think, well, maybe the vagina will bring down this state for real.’

And while the voices of younger people, speaking for change, seem to be growing louder, they are always challenged. “Authorities, the eldest men in families, any ultra-right activists manifest this collective violence against women, over their bodies, over freedom,” Apakhonchich noted.

But nevertheless feminist and LGBTQ+ artists in Russia remain optimistic about the future. “A generational change is underway,” argues Lomasko. The ever-growing interconnectedness facilitated by the internet continues to offer hope. “New generations are intensely focused on Western living standards: this includes the creation of a safe environment for all, respect for all social groups.”

Tsvetkova, whose name is based on the Russian word for flower, will next head back to court at the beginning of May. Even in the unlikely event of her acquittal, the consequences seem endless. “For a year now, my temperature has been 34.35 degrees Celsius, it does not rise any higher, [I have had] dizziness, nausea, many different ailments,” said Khodyreva. “Even when everything is over, it will haunt me for a long time.”