‘It feels like trying to swim in the middle of a giant storm’ – the artist on the art of Facebook metaportraits, machine vision, and meaning in the age of the pandemic

From training his astro-telescopic lenses on military bases (Limit Telephotography, 2005–), to launching an artificial star into outer space (Orbital Reflector, 2018), Trevor Paglen has always been fascinated by the politics of ‘looking’, the weaponisation of technology and alternative futures. Much of the artist’s recent body of work has turned to the ways in which our world is increasingly governed by forms of machine vision and data extraction – often, machines seeing for other machines – from facial-recognition technology to social-media advertising. It’s a throughline running across his new exhibitions at Pace Gallery, London, and at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh.

ArtReview Has lockdown changed the way in which you make art?

Trevor Paglen I guess some artists are people who like to hang out in their studios and weren’t necessarily bothered one way or another. But I’m the exact opposite – so much of my work is going out, travelling places, looking at things and talking to people. That all became impossible. So, on the one hand, the logistics of the work had to change a lot.

The other part of it is that the things you’re thinking about change a lot. This time has been many, many things, but in terms of making art, it’s been a moment at which there’s been a huge change in the way that images mean things. Some small examples of that might be: suddenly an aeroplane in the sky takes on a different meaning; suddenly a handle of a gas pump takes on a different meaning; suddenly a runner speeding past you means something different. There’s a massive change in your relationship to the world around you, in terms of what kinds of associations you have, and in the meanings that you ascribe to different things and different kinds of images.

Working within that context is really intense – certainly in the way I approach making art, which means finding things that are familiar and then subtly shifting those connotations around. I think all of us, as artists, are used to being able to do that, in a way. Having a sense of control, or at least guidance, regarding the relationship between an image and what its meaning is. During this time, there are such larger forces at play, determining the meaning of things: it feels like trying to swim in the middle of a giant storm, and all the waves are 50 feet high. Good luck with you deciding what you want things to be!

AR The pandemic has also laid bare all kinds of inequalities – today, a scandal is breaking in the UK over students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds being awarded downgraded results following the cancellation of final exams, through an algorithm that determines grades according to schools’ historic results. And it reminded me of your work, which often examines the inequalities that are baked into these datasets and their damaging real-life implications.

TP Yes, so the algorithm consistently overrides the human scores assigned to those kids. For me, it’s been an intense time of, on the one hand, fear, and on the other hand, mourning. Being in New York, there’s what you talked about – these inequalities laid so bare, and producing so much senseless suffering and death, visceral, non-abstractable. And then being disconnected from other people, with

the only forms of connection through extremely mediated platforms such as Zoom or social media. These are platforms that are basically weaponised against you, which are preying on your social interactions and transforming that sociability, mining and extracting value from it.

I guess the culmination of these factors is what’s behind how my new body of work came together. In the middle of all of this, in New York, especially in April and May, you’re totally locked down and you can’t interact with other people. And at the same time, you’re afraid of the material world – as if all of its infrastructure is against you, in some way. But it’s quiet. You’re hearing sounds that you haven’t heard before. Nature in springtime is blooming – it’s crazy, those smells and colours, partly perhaps because you’re not going outside very much. All of those sensory experiences are so much more intense. For me, it was looking at that, and thinking about flowers and art history. If you’d told me ten years ago that I’d be doing a show about flowers, I’d look at you as if you were out of your mind. The biggest cliché! But yes, flowers and skulls – these are the themes running through Bloom, the exhibition at Pace. Historically, these have been intensely allegorical images.

AR The seventeenth-century vanitas painting tradition…

TP Yes, exactly. Even looking at baroque allegorical paintings and then at this moment, feeling very baroque, very dark at the same time. So I’ve been working with flowers and that tradition of imagery: life, fragility and death. And thinking about that in relation to AI, and the role of technology now, in how it shapes how we interpret things, shaping our sociability, shaping how we interact with each other culturally and politically.

AR So in Bloom (2020), there’s this idea of machine vision, looking at flowers through the eyes of a system?

TP I’m taking photographs of flowers, and then using AI systems that do what’s called ‘deep saliency’. They are trying to use artificial intelligence algorithms to interpret what is going on in an image, to infer what the different kinds of objects are in an image, what the different kinds of textures are in an image and trying to figure out how closely related they are to each other. The colours and the images are coming from AI systems that are trying to interpret what the different parts of the image are.

AR Similar to the ‘training sets’ your work has used before.

TP It’s built on training sets. So these are AI networks that are trained on sets of thousands of different kinds of images, and then to use those sets to say: this is a flower, this is a leaf, this is a branch; this is a hard texture, this is soft, this is smooth. And those neural networks are used to distinguish what the particular parts of an image are.

AR Other artworks also look further back into the histories of these predictive models.

TP There’s a skull, The Model (Personality) (2020), done in the manner of late-nineteenth-century phrenology, a practice in which people would equate different parts of a person’s skull with different parts of their personality. I’m looking at that in relation to personality models built into AI systems, such as IBM’s Watson, which will analyse pictures of you, analyse text that you’ve generated, your likes on social media, and then try to model your personality, which is used in everything from marketing to law enforcement.

And there is a larger theme in the exhibition that is about standardisation, and what kinds of abstractions are made of the world by technological systems. The Standard Head (2020) looks at the history of facial recognition. It’s specifically looking at the first attempt to do facial recognition with a computer, done by a guy named Woody Bledsoe during the 1960s – all funded by the CIA. One way of doing facial recognition is you basically map out all the features of somebody’s face, as if it were a fingerprint – the corner of the eye, the corner of the nose, the mouth – you map out all these key points, or facial landmarks, and then you see what is the proportion of all of these landmarks to each other. Bledsoe created all of these keypoints in reference to an abstract model of a human head that he called ‘The Standard Head’.

That standardised face is just a mathematical abstraction of what a human face looks like. I was able to get hold of Bledsoe’s archives (through my friend, the researcher Stephanie Dick), of the measurements of ‘the standard head’, which I was able to reproduce in a three-dimensional model – this fictional, abstracted head that is the basis for the sculpture. I’ve been thinking about the origins of these standardisations, the cornerstones upon which these technologies are built.

AR And the exhibition will also be streamed online?

TP There’s this whole other part of the show, Octopus (2020), which is thinking about the situation we’re in. What does it mean to do an exhibition under these circumstances? Normally you do an exhibition, it’s assumed you go to the space, you see the show and a photographer documents it and that goes online. You see the ‘documentation’ online. Well, what if we thought about the exhibition neither being entirely in the space, nor entirely online, and use that as a foundational principle for thinking about what an exhibition is? So, what we did was take the equipment from a project I’ve been doing with the Kronos Quartet called Sight Machine (2017), which is a performance where we have all these cameras in a wild, crazy computer-vision system that surrounds the musicians. We adapted that and thought: what if we made an exhibition that was conceived of as being online in the first place? But not how art fairs have been building 3D models which you walk through. We’ll use streaming cameras as a paradigm.

When the show opens there will be 20 different cameras installed throughout the space, and the cabling comes from the ceiling. If you go into the exhibition space, you’ll see cameras and cables coming from above, like a jungle. And all of those cameras are streaming images of the space onto a website, where you can see all these different views in real-time. Some of the cameras are using object detection and tracking people walking around the space, which you can view from the online platform. But the online platform will also ask you for permission to use your camera, which will then, with your permission, stream you onto monitors in the exhibition space – so visitors will look up and see the faces of people online looking at the exhibition. It will be really weird; it will feel like you’re in a model. I’m trying to play with this stuff about where the exhibition is – which is indicative of our times.

AR You’re also working on Opposing Geometries at the Carnegie Museum of Art, which continues this work you’re undertaking into machine vision.

TP The Carnegie show is based on looking at the works I’ve done around computer vision systems and AI over the last decade, and their different approaches. Over the years, at my studio, we’ve essentially written a programming language that we can use to take images, or videos, and then look at them through the eye of a self-driving car, or a guided missile, or a facial recognition system. And then it will draw a picture or representation of what that computer vision system is ‘seeing’ in a particular image. A number of works reinterpret classical Western landscapes, which think about the relation between photography and colonialism, technology and power. And those are questions that are everywhere in this history of photography – so thinking about how you update those questions for computer-vision systems, which I personally think of as a kind of photography, actually. A kind of autonomous interpretation of photography.

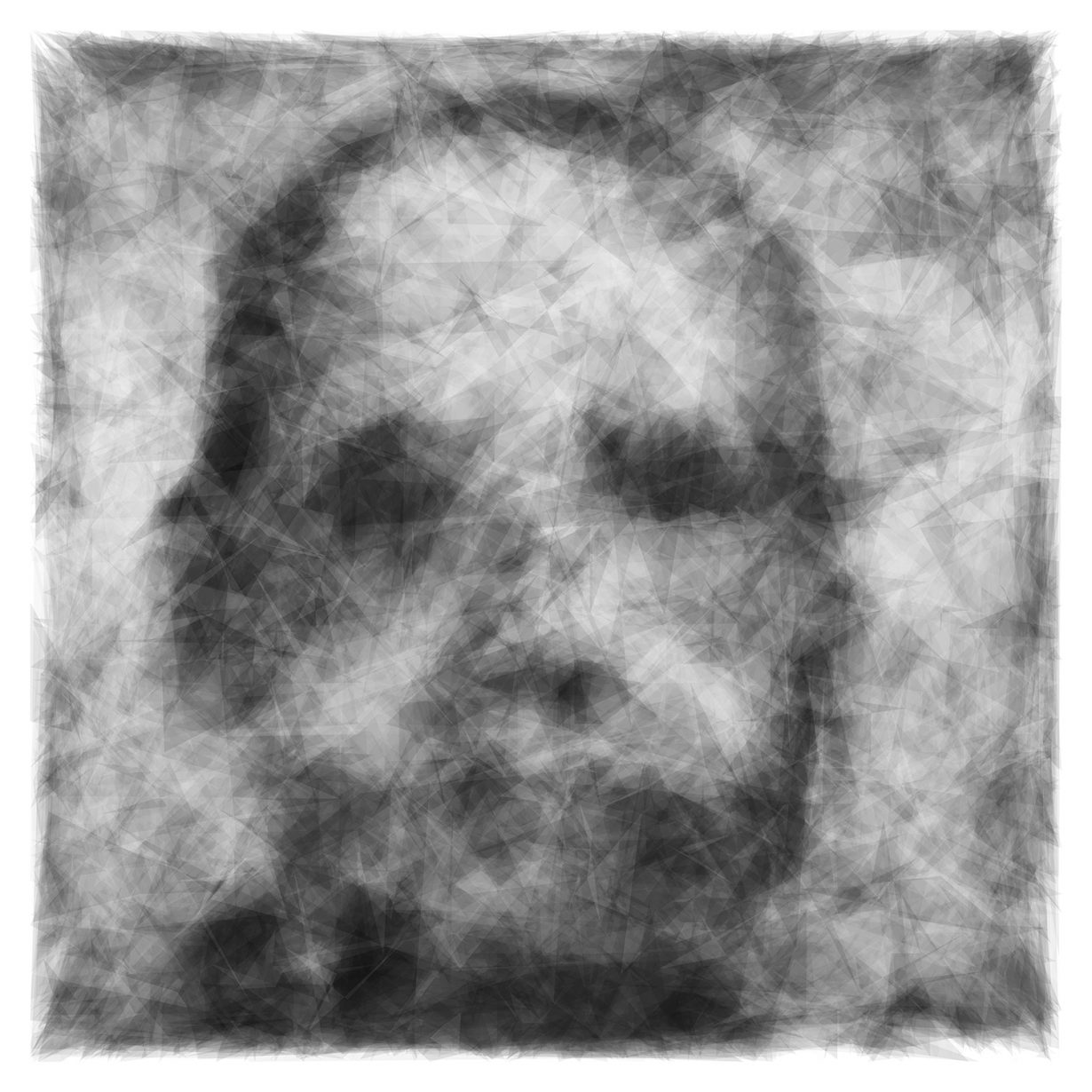

Another thing we can do with this programming language is extract from computer-vision systems the images or models that the system is building for itself, in order to understand other kinds of images. In some versions of facial recognition systems, it will be trained, ‘taught’, how to see a particular person. For example, Facebook has some of the best facial recognition in the world. Why? Because they have everybody’s pictures, and because everyone has labelled their pictures. So, to vastly oversimplify, say there are 10 pictures of you that your friends have dutifully tagged as belonging to you – Facebook will take these and abstract them into a metaportrait of you. And then take all the other portraits of other humans in the world. But what I do is take your metaportrait, and then subtract what you have in common with all the other metaportraits. What I’m left with is a portrait that is a signature of your face.

AR And what do you see?

TP I did a series of works, training facial recognition software on the faces of revolutionary philosophers and artists, and making portraits of them based on this system. In the Carnegie exhibition, there’s a portrait of Simone de Beauvoir, as modelled by a facial recognition system, for example, and of Frantz Fanon, Samuel Beckett, all titled Even the Dead Are Not Safe (2017).

It’s interesting. One would imagine that you would end up with something very angular, or very sharp. In fact, the opposite is the case. You end up with something very ghostly looking, very impressionistic. And the reason for that is that you’re seeing distributions of properties or values. In the metaportrait of your face, the region around your eyes is actually not a super-specific point as far as the metaportrait is concerned – it’s a range of distributions: most likely to be this proportion, a little bit less likely to be this proportion, could be this proportion. It’s all gradients-based with different probabilistic values of where different things will be. But when you translate that into an image you get something very blurry.

AR It feels like there’s a connecting line – that haziness – from the clunky, racist classifications doled out by the facial recognition in your work ImageNet Roulette (2019), and even back to your earlier blurred photographs of drones speeding across night skies.

TP I think, especially with the machine-vision work, but perhaps through all my work, so much of it is about uncertainty, and what meaning is, how meanings are generated. What is an image, and what does an image say? For me, that is a fundamentally unanswerable question and I think that’s where those forms of blurriness, physically and metaphorically, come from. The denial of that uncertainty is the bedrock of a lot of the AI and computer vision out there. And the denial of that uncertainty is weirdly where a lot of the politics of computer vision come from. It’s that fixing of meaning and that classifying of people; attributing certainty to things that are, fundamentally, amorphous.

Trevor Paglen, Bloom, runs at Pace Gallery, London, from 10 September to 10 November 2020. Opposing Geometries, at Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, is on view from 4 September to 14 March.