Trust Me at the Whitney Museum of American Art assembles photographs from the Whitney’s collection by artists who foreground intimacy, care and connection in their work

Writing in Camera Lucida (1981), theorist Roland Barthes lingered on the photograph’s punctum, an affecting point of attention that he described as ‘the accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me)’. As Elspeth H. Brown and Thy Phu have argued in Feeling Photography (2014), Barthes’s text is an important precursor of contemporary forms of photographic analysis that fold feeling into their critical frameworks, often elucidating the connective tissue between photographer, subject and viewer. Trust Me, which assembles photographs from the Whitney’s collection by 11 artists who foreground intimacy, care and connection in their work, makes a strong case for the place of feeling in photography, as both a mode of analysis and a means of making. An exhibition that featured a lesser selection of artists might have fallen flat amid a spate of COVID-era shows presented in a similar emotional register, but this fiercely tender grouping holds its own.

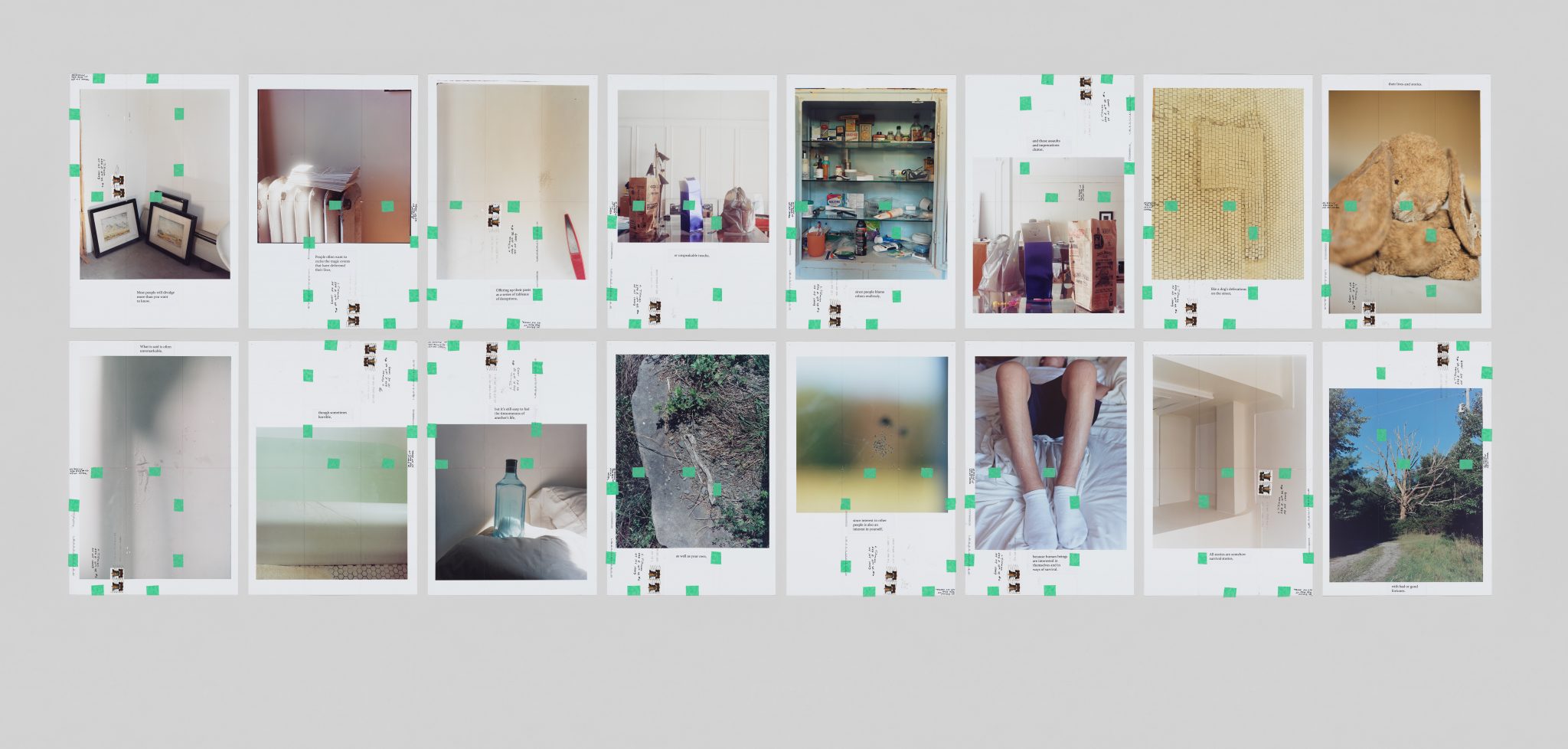

Intimate exchange and collaboration are integral to these works, down to their material construction. Take the titular piece, Moyra Davey’s 16-part installation Trust Me (2011). Tacked to the wall in two neat lines, Davey’s photographic vignettes expose miniscule traces of time’s unsightly passage: a blue bottle depleted of its contents; dust accumulating in a nondescript corner; the uneven pattern formed by waterlogged tiles and grout. Each photo- graph bears evidence of having passed through the postal system: creases from folding, green tape, postage stamps and the address of writer Lynne Tillman, the artist’s friend. Receiving the photos from Davey, Tillman appended evocative fragments of text from her 2006 novel American Genius: A Comedy to each, determining the images’ order. The work becomes a protracted conversation. Likewise, Genesis Báez’s Crossing Time (2022) is formally predicated on intimacy. In the inkjet print, Báez’s mother holds up one end of a taut thread; its parabolic shadow, cast on the wall, is taken up by the artist’s shadow at the other end. A picture of intergenerational connection in a diasporic family, this intricately staged scene necessitated that the women physically collaborate – each trusting that the other would hold up her end.

Much of the portraiture on view not only reflects care, but also in a sense administers it by forging a space for underrepresented subjects to see themselves. Barbara Hammer’s silver gelatin print Barbara & Terry (1972) depicts the artist with her then partner Terry Sendgraff, both nude and entwined among tall fingers of grass. The couple’s vulnerable gesture – their exposure – is all the more generous in light of the lack of self-defined images of lesbian intimacy around the time of the photo’s creation. Lola Flash’s nearby portrait Untitled, Provincetown, MA (1990) depicts a figure wearing a phallus-emblazoned T-shirt, who meets the viewer’s gaze from under a corona of leaves. The colours – all saturated and inverted – are the product of Flash’s ‘cross- colour’ technique, which they developed as an art student during the 1980s by printing onto negative photo paper. As it challenged conventional notions of a ‘good’ photograph, which were trailed by conventional notions of a ‘good’ life, this technique also rendered Flash’s subjects – often queer people of colour – anonymous, conferring a degree of protection and critical visibility at the same time.

Archives can be powerful sites of connection and repositories of feeling, and rephotography can convey the intensity of that encounter for the photographer. To make X post facto (6.7) (2009–13), a sweeping inkjet print in which a dark screw protrudes from hazy strata of grey, Muriel Hasbun rephotographed one of the dental X-rays that her father, a dentist and photographer, took to identify those who died during the Salvadoran Civil War (1979–92). Enlarged to the point of abstraction, the intimate space of a stranger’s mouth becomes an expansive, layered memorial: to the artist’s late father; to the deceased individual, whose dental implant is pictured; and to the 75,000 reported dead from the brutal civil war. Also feeling (and appropriating) their way through the archive, Mary Manning used their deceased father’s old camera to rephotograph some of the photos he regularly snapped of roadside wildflowers. A simple elegy comprising two floral pictures mounted on board, His Estate (2022) reproduces their father’s creative output and celebrates his desire to attend to, and photograph, everyday beauty. We can’t know what Barthes would have thought of this work – whether a punctum might have surfaced for him, particularly with the death of his mother, which shaped his thinking on photography, on his mind – but we might return to his words: ‘The suspension of images must be the very space of love, its music’.

Trust Me at Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through February 2024