An archive exhibition showcasing almost half a century of sonic resistance in the Philippines struggles to communicate its contemporary significance

Lakbayan – the Tagalog word for ‘journey’, which has, in turn, come to define a form of mobilisation in which people from the peripheries, both geographically and ideologically, march to the capital to voice their concerns and demands – is an archive show spanning almost half a century of sonic resistance in the Philippines. On ‘display’, attempting to represent revolutionary protest music of the Philippines from the 1970s to the present, are 18 featured songs, a documentary, various forms of archival material and two ‘sharing stations’, at which attendees can record their own aural histories. It’s curated by Dang a Dang Radio (which takes its name from the Ilocano word dangadang, for struggle), which formed towards the end of Rodrigo Duterte’s presidential term (2016–22) as a collective, research platform and online radio programme. Despite lakbayan’s thunderous tunes, revolutionary theme and evident energy, it struggles to communicate its contemporary significance and qualify the ‘solidarity’ its exhibition text claims to seek.

LAKBAYAN succeeds in contextualising the origins of the music collection that dates to the dictatorial era of Ferdinand Marcos Sr (1965–86). We get some sense of the music’s revolutionary power in the past: Filipino and English pages from the songbook of the first known vinyl of Filipino protest music, Bangon! Arise! (1976), are affixed to two temporary pink walls. Here, the viewer can read essays on ‘The Philippine Struggle for Independence and Democracy: A Few Historical Notes’ and ‘To Struggle and Sing: The Role of Revolutionary Songs’ that further historically ground the exhibition. Each song page includes musical notation, Filipino lyrics, an English translation and additional context. Immediately behind these walls is a projection of Jose Luis Clemente and Nil Buan’s 1984 documentary Daluyong (Waves), which depicts the lakbayan known as Lakad ng Bayan para sa Kalayaan (People’s Walk for Freedom) that spanned 84km, from Southern Laguna to Manila. Towards the end of the film, a live recording of Jess Santiago’s beloved Martsa ng Bayan (March of the People, 1981) overlays clips of people marching.

This noise, coupled with music from three listening stations that carry through the space, enforce the sense that revolution is loud. The listening stations, though, are the exhibition’s main feature. They allow visitors to sit within a semicurtained space while music – ranging from marching anthems to indigenous and folk tunes, conceptual tracks, blues, rock and rap – in Filipino languages plays from speakers above. For those who do not understand the languages at play, there is a song book with original lyrics and English translations; but if you don’t speak English, you may struggle. Despite its claim of calling ‘for solidarity’, there’s no clear sense of the exhibition making itself accessible to anyone who is not Filipino, given the extent to which it relies on knowledge that many visitors won’t have.

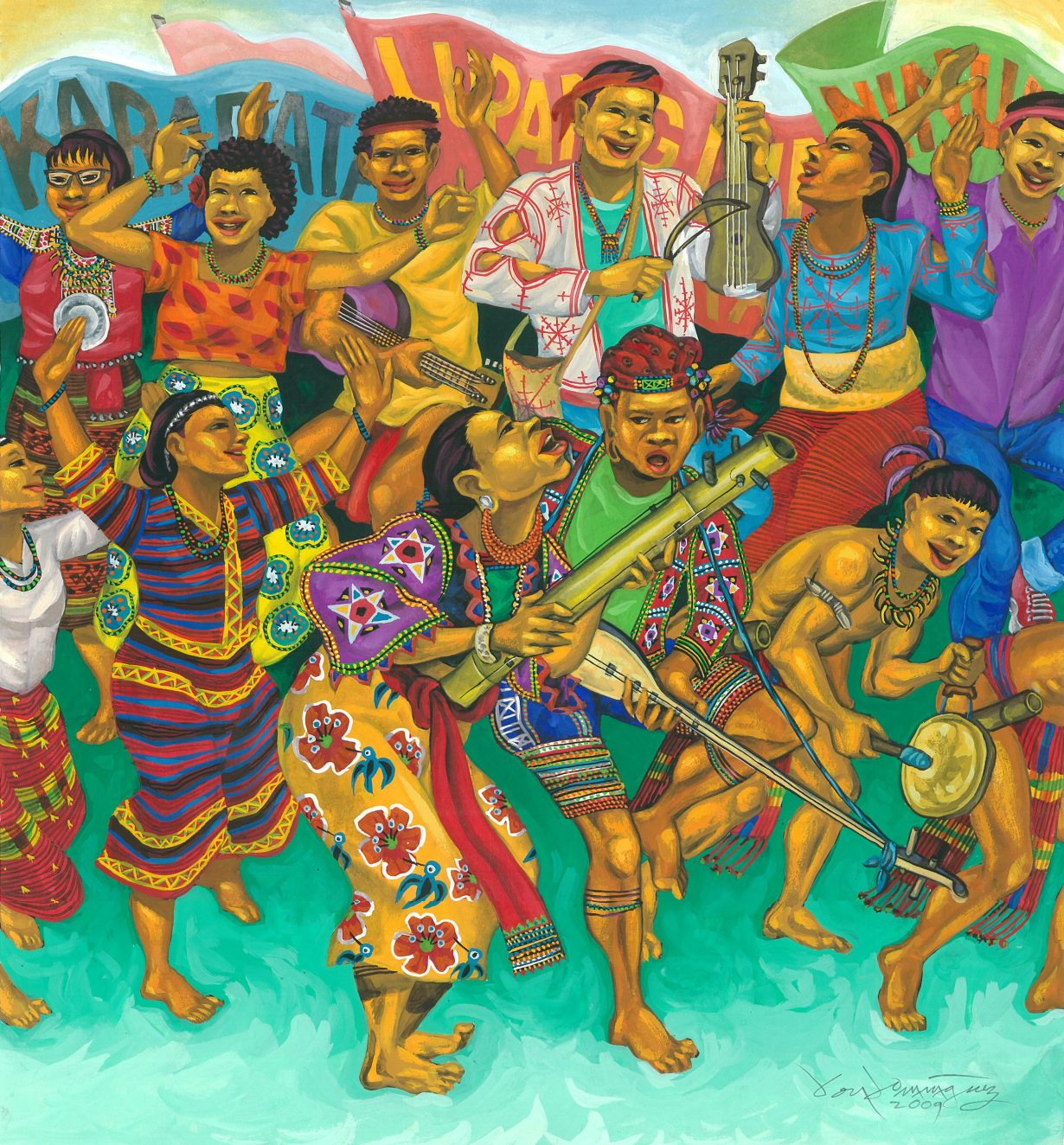

Take, for example, the pink-painted walls. The pink is a clear, though unacknowledged, homage to the 2022 Liberal Party presidential candidate Leni Robredo, whose campaign colour was pink. She ultimately lost to Ferdinand Marcos Jr, but the colour pink endures as a symbol for the left. Three contemporary digital artworks by artist Federico ‘boyD’ Dominguez are also displayed here: two black-and white digital prints on lightboxes, titled Sandugo (One blood, 2016) and Pangiyaki, I Matoy (A time to fight till death, 2017), show a group of diverse people who represent various sectors in the Philippines as they protest; then a large colourful digital projection on the back wall titled Dayaw (Praise, 2009), which features diverse Filipinos singing, marching and playing instruments with banners waving behind them. It’s not quite clear what these works, which come from a distinct aesthetic tradition of social realism, add to the archival material, however. A central column, lined with rows of over 100 cassettes and CDs dating from 1982 to 2022, gives a much better sense of what protest visuals look like and how they have (or haven’t) changed over time.

Ultimately, however, the visitor is left with the enduring question of why this exhibition is taking place in Berlin. In their exhibition text, Dang a Dang Radio cite the necessity of preserving dissenting archival material from the Marcos Sr era, because the former president’s son – the current president – has successfully revised perceptions of his parents’ violent period. But they fail to make clear the wider, and current, contexts that might make the exhibition more resonant to those unfamiliar with its intricacies. Historically, the aural platform has been both specifically influential with the Philippines and a particular target for government repression: more radio journalists have been killed than journalists operating in any other medium. The works on display also barely acknowledge that activists and artists are being targeted for their dissent today. The volume can be raised, but is it enough to make you listen?

LAKBAYAN: Voices of Resistance from the Philippines at Savvy Contemporary, Berlin, 19 March – 9 April