A year after Jina Mahsa Amini’s death, a new book anthologises texts and images from the experiences of Iranian women in revolt

‘Every day, thousands of sad and thousands of sweet acts are taking place at the same time’ describes an anonymous writer in Woman Life Freedom: Voices and Art from the Women’s Protests in Iran. On the one hand, people feeling the stirrings of renewed hope are ‘a lot kinder to each other’. On the other hand, there are arrests: ‘a lot of activists and journalists – many more than before’. In this anthology of writings, artworks and photographs, editor Malu Halasa collects works by household-name artists of the Iranian diaspora, including documentary photographer Hengameh Golestan and author Kamin Mohammadi, alongside works by emerging artists, including students. Many are anonymous, writing from Tehran and fearing retribution: arrests, torture, the death penalty. What unifies them is their determination against all odds. The Woman Life Freedom movement exists in response to real-life tragedy; the title itself is a translation of the protest cries in Farsi and in Kurdish, sparked by the murder of 22-year-old Jina Mahsa Amini in Tehran. On 13 September 2022 Amini was detained, accused of breaking the law for wearing a scarf and robe rather than a hijab. She was beaten in a police cell and died in a hospital on 16 September. Authorities attributed her death to a heart attack, while hospital photos showed wounds indicative of a brain injury sustained through a trauma to her head. The erasure of human lives, and the truth about them, is a form of memoricide – the destruction of stories we share as human beings. In the face of such horrendous acts, what can art possibly do?

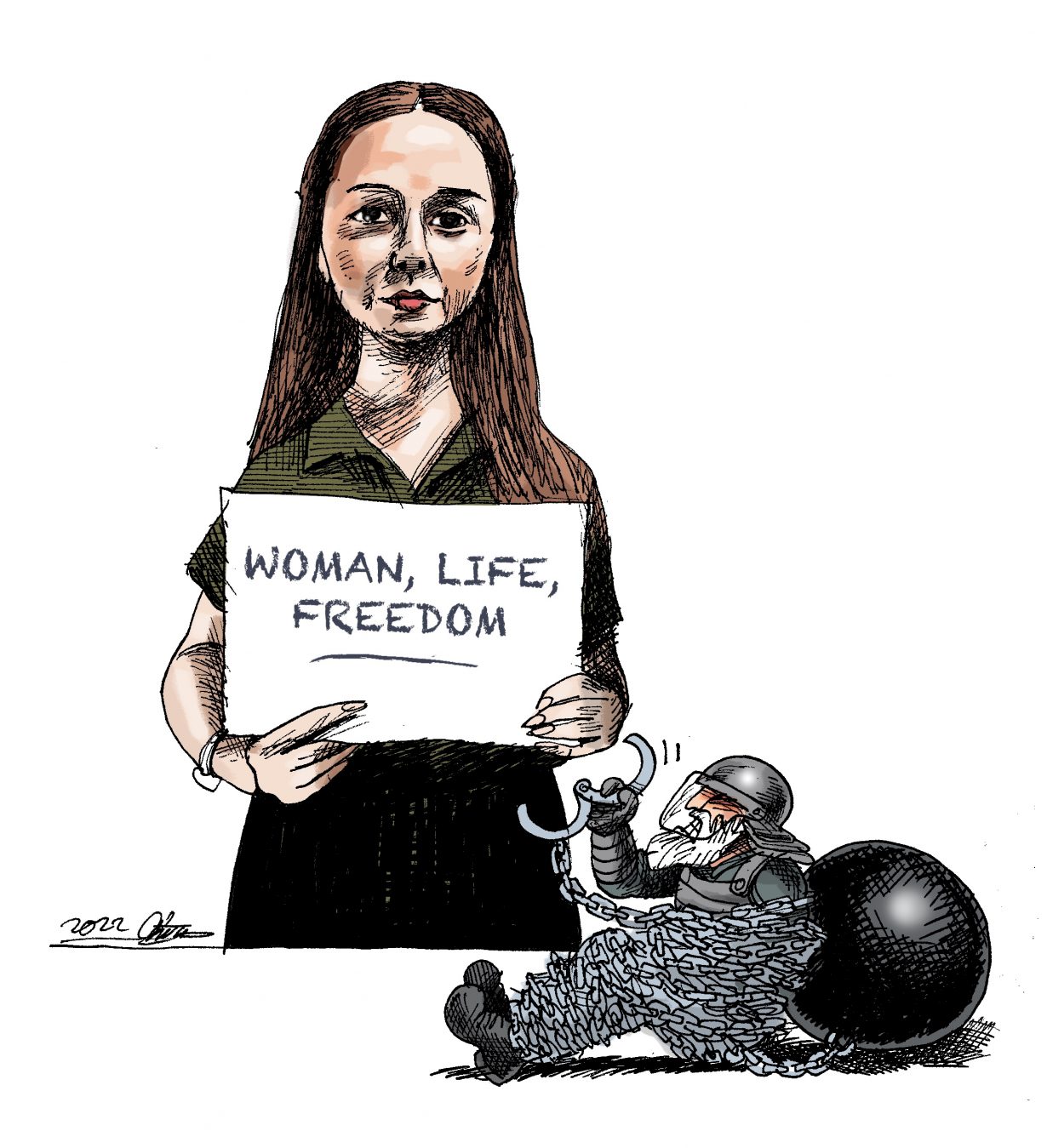

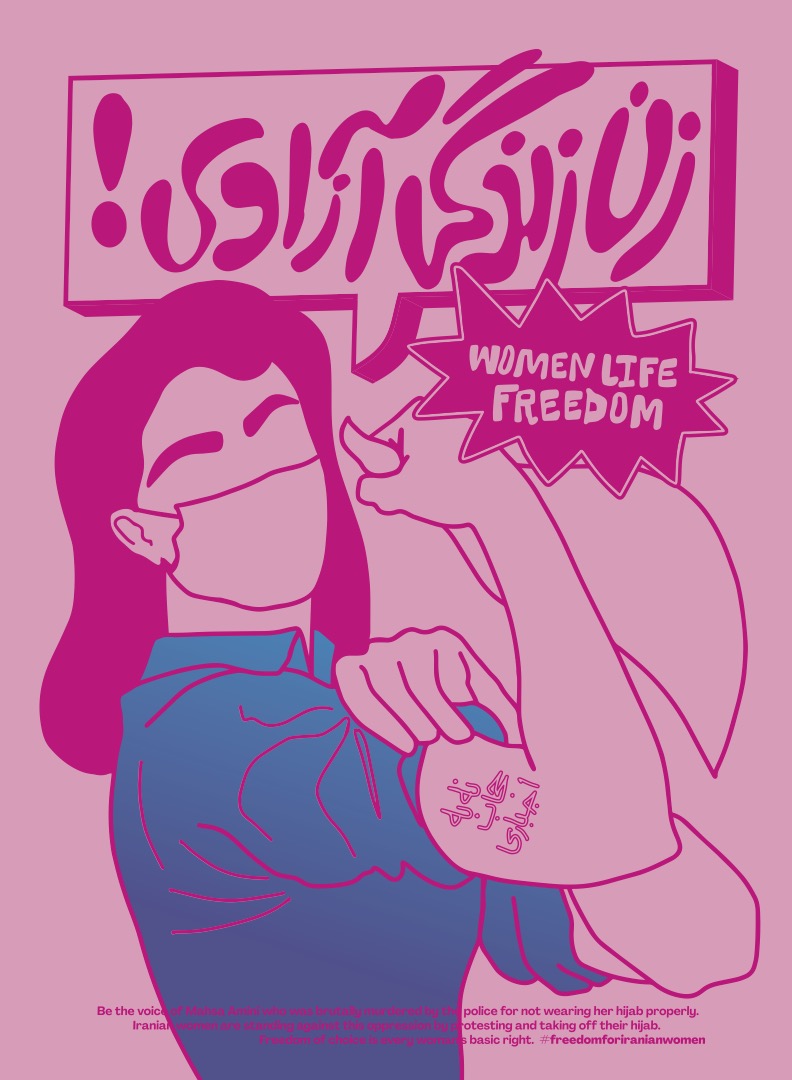

In the chapter ‘Keeping the Revolution Alive: Art for Social Change’, illustrator Roshi Rouzbehani explores why authoritarian regimes attack the arts, writing that the insistence that ‘good’ art is necessarily apolitical is often ‘rooted in the belief that art should be an escape from the realities of the world’. She believes, however, that this is now seen differently: ‘people are noticing that art is not created in a void and cannot be separated from the society in which it is created’. Reading this book – and thinking more widely about ongoing atrocities – it’s crucial to keep in mind the levels of censorship met by artists in different parts of the world today, as well as the levels of risk they face when sharing their work. For Mana Neyestani, in his essay ‘Drawing the News’, art is the only way of escaping the chokehold of autocracy: ‘If one feels that the influence of political art is stronger in Iran than in Western countries, it is only because of Iran’s closed political system. In fact, cartoons, graffiti, photographs, to name a few, are the only ways to “breathe”.’

If creativity, as a means of protest, is often limited to the production and circulation of forms society recognises as art, then this anthology makes a strong argument for the political potency of visual signifiers that lie outside of the traditional white cube. A photo essay by Shiva Khademi explores how a fashion movement can engender real change: walking the streets of Tehran with ‘The Smarties’, Gen-Z women who dye and show their hair in defiance of the authorities, despite the potential consequences. ‘The women I met were as diverse and complex in personality as in appearance’ Khademi writes. ‘For them, their hair colour was not superficial; it represented a freedom they were willing to fight for […] I think the Smarties were the pioneers of the shift we’re now witnessing, and their numbers have increased too.’

There are other examples of pioneers throughout the book. In ‘Rebel Rebel’, Halasa looks at Iran’s pre-revolutionary feminist icons as depicted by artist Soheila Sokhanvari, whose practice involves mixing colour pigments with egg tempera and painting on calf vellum: this is an aesthetic rooted in tradition. ‘In the ornate settings of Persian miniatures’, writes Halasa, ‘more attention is often paid to the background than the foreground.’ This is true of Sokhanvari’s portrait of the prolific singer Googoosh: the wallpaper, floor tiles and singer’s dress are vividly hued while Googoosh herself is drained of colour. After all, time has passed since the 1970s, the days of Googoosh’s meteoric rise to fame as a singer in Iran through to the time of the revolution when she was banned from singing. In the pre-revolutionary time memorialised by Sokhanvari, Googoosh’s face appears in grey hues, like a black-and-white photograph from a time that can never be regained.

‘Apparently, the world has heard our voice this time. At least that’s what we’re told’, Sara Mokhavat writes wearily in ‘On the Pain of Others, Once Again’. But it’s hard to believe: ‘We are too exhausted, too anxious, to sift the truth from propaganda.’ Even if believed, can the solidarity of people living in the West be counted on as genuine? And is solidarity enough? Mokhavat questions posts on Instagram purporting to support the protests, like well-known French actresses ‘cutting off bits and pieces of their hair to show sympathy for the women of Iran’. Juliette Binoche started it, cutting off a strand of her hair, holding it to the camera and declaring it an act ‘for freedom’. Other famous actresses followed suit. For Mokhavat, the gesture feels perfunctory: she is forced to reflect on how different her circumstances are from theirs: ‘I wish I had these women’s lives’.

For people in Western countries, what does going beyond expressing comfortable solidarity actually look like? It is so hard to read Mokhavat’s wish to have the basic freedoms of women in the West, while being cognisant of the politics that currently prevent those freedoms. We read for awareness, for galvanisation. This book joins, for example, Marjane Satrapi’s immensely popular series of graphic novels Persepolis (2000), which gives a personal view on the history of women’s rights in Iran. We can join #EyesOnIran – a campaign by Iranian activists to ensure international audiences and institutions keep the spotlight on Iran. We can back human rights organisations in their mission to support the rights of Iranian women. We can attend marches or vigils taking places internationally on 16 September 2023: a show of solidarity across borders. There is no conclusion, no ending to this Woman Life Freedom book – how can there be, when new horrors come to light daily? And, soberingly, there is no end to the bravery and effort of those who risk their lives when they proclaim ‘Woman Life Freedom’.

Frances Forbes-Carbines is a writer with recent pieces in The London Magazine, Antigone Journal and Observer