“The paintings are, in a way, physical gestural expressions of the algorithms that I embody”

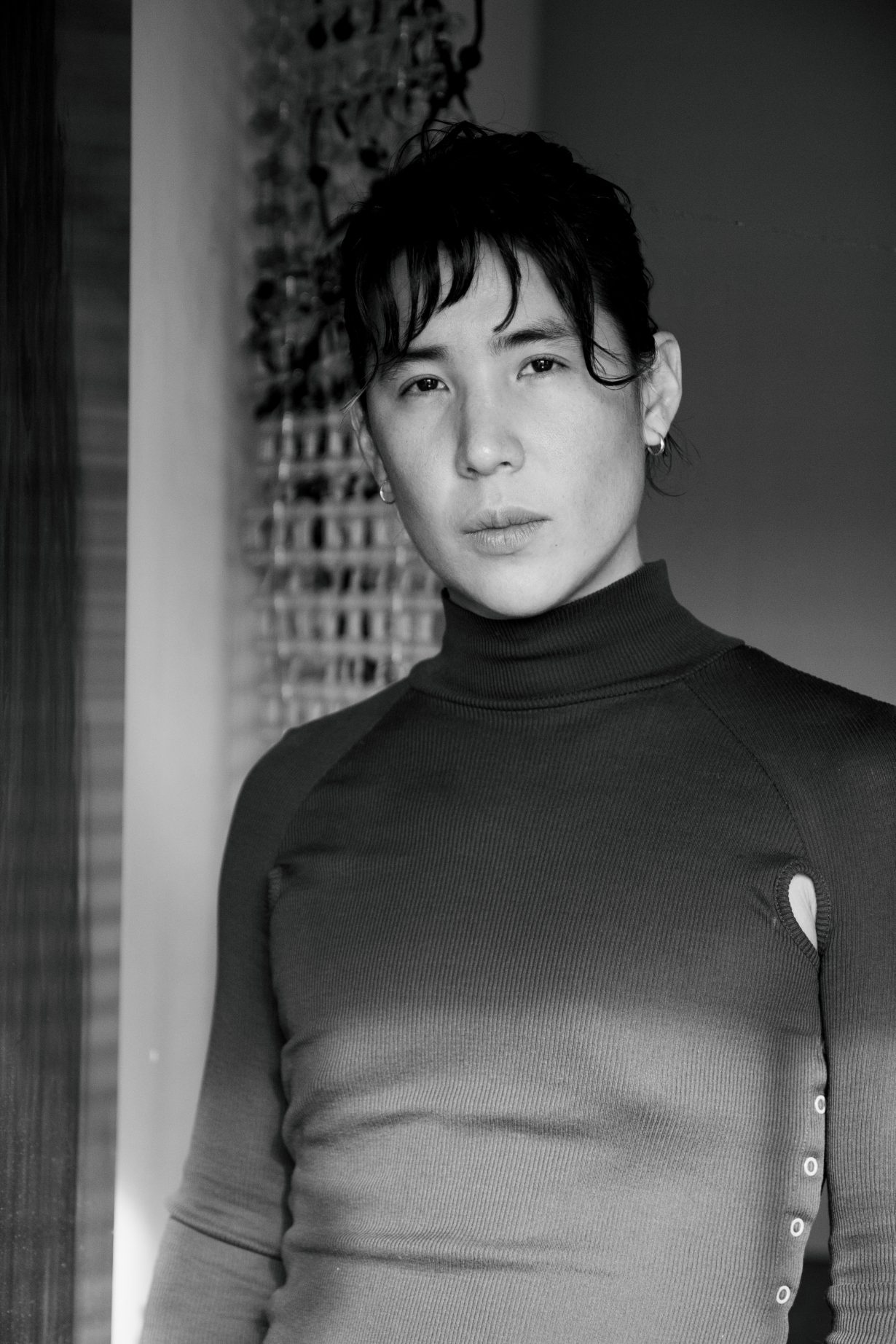

When the Whitney Museum of American Art acquired a painting by WangShui in 2021, the museum uploaded it to their collection website and labelled it as a sculpture. “There are certain things that I’m expected to create,” the artist told me, adding that “the current climate in the artworld prevents people from seeing things as they are”. Indeed, up until 2020, the California-born, New York-based artist’s work took the forms of video and moving-image-based installation and sculpture. But for the last three years they have been developing a unique painting practice, spreading oils as thinly as possible to illuminate abrasions made on aluminium panels, and sometimes collaborating with artificial intelligence to develop the compositions.

No matter the medium, though, WangShui roots much of their practice in exploring concepts of perception and (in)visibility: not just how humans see things, but how we understand and interact with different aspects of the world – be they natural or synthetic, physical or immaterial, alive or inanimate – and how, in turn, these aspects interact with or become part of us. WangShui understands such relationships as inherently intertwined and ever-evolving, as expressed in works like Gardens of Perfect Exposure (2018). The live installation consists of detritus (ranging from chrome bath fixtures and laminated hair to glass globs), silkworms, selfie ring-lights and camcorders, which capture the silkworms’ movements and growth; the recording is upscaled and projected in real time onto the walls of the room in which the work is installed. Historical and philosophical references aside, the work is, on an essential level, “about immersing the viewer within a mediated loop of consumption”, the artist says.

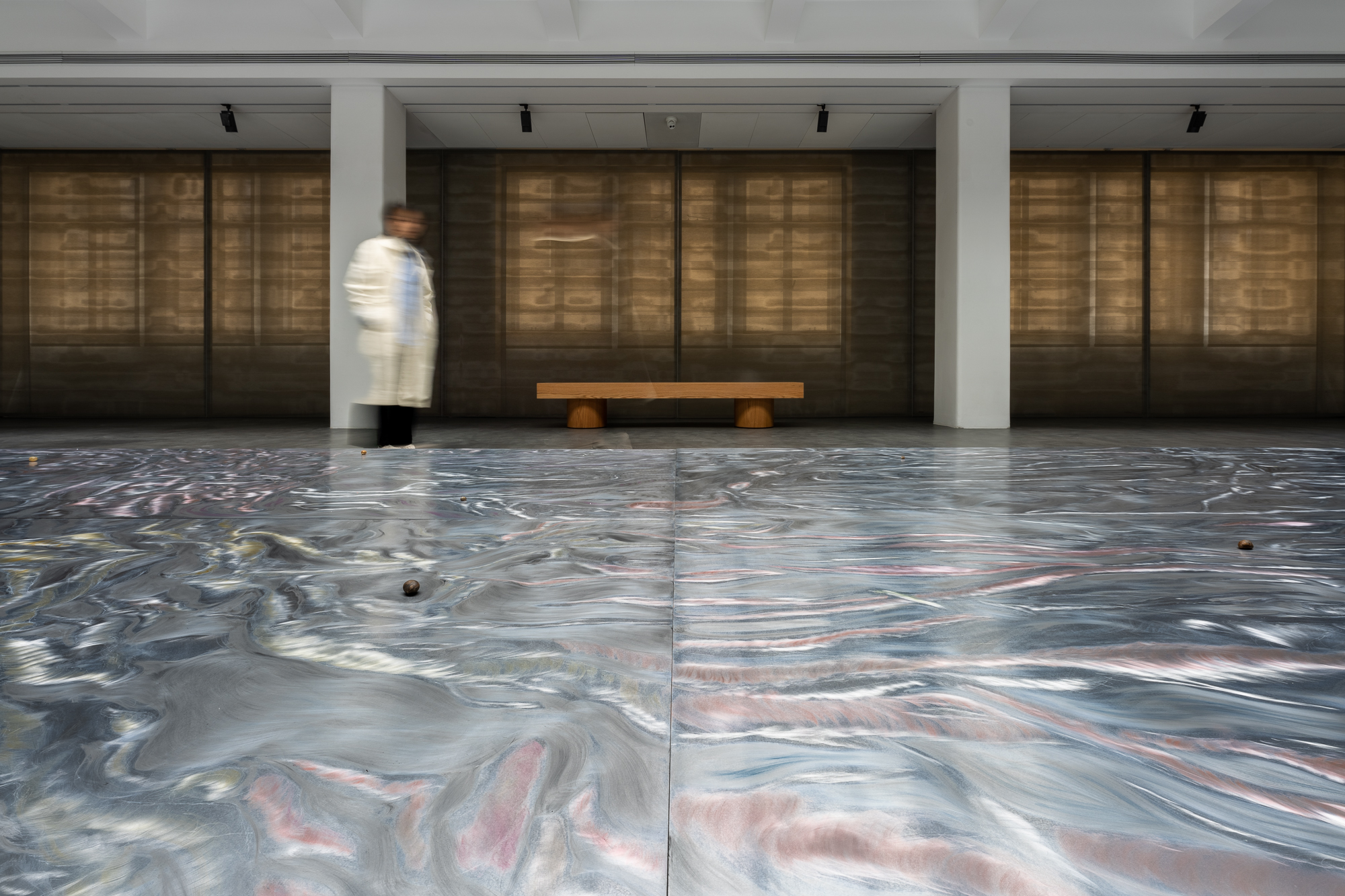

In WangShui’s paintings, these same concepts are explored, albeit perhaps less obviously at first glance. As part of their first solo museum show, currently on view at Shanghai’s Rockbund Art Museum, eight paintings are installed on the floor of the main gallery, with an additional series depicting abstracted, mythical organisms hung on fabric-covered walls on the upper level. And come September, they will exhibit a new suite of paintings at Haus der Kunst in Munich, alongside a multichannel artificial intelligence simulation. With both shows, however, invisible forces are also at play: in Shanghai, a custom algorithm measures ultrasonic frequencies in the space and uses the data to generate a new layout for the floor paintings, which are then manually rearranged accordingly every Friday. In Munich, the live evolution of the AI simulation will similarly dictate new configurations for the paintings in the next room. “The movements of the paintings are real-time visualisations of the backend programming,” the artist explains. In this way, the paintings are not fixed objects in space, but data points in a recursive machine-learning loop.

When I called WangShui shortly after the opening of the Rockbund exhibition, we decided to focus our conversation on the act of, and their intentions with, painting – a topic that led us from Claude Monet and Francis Bacon to artificial intelligence to their obsession with reality TV.

Relaxing, Smearing

ArtReview You have a background in video and moving image, so what led you to painting?

WangShui I have always wanted to paint, but it was probably galvanised by screen fatigue in the early days of the pandemic. Before the pandemic, I had never had an actual studio; I was always doing residencies. But then, during the early pandemic, I was staying at a friend’s place in Upstate New York and all of a sudden I was working in one place, so I started testing every single type of paint medium and different surfaces. It was the first time I had the time and space to experiment with painting and find out what made sense to me in terms of the process.

Also, when I go see art, I mostly see paintings by dead masters. I have a deep interest in the history of representation. For years, my moving image work has been an attempt to deconstruct the material, optical and psychological dimensions of screens. Painting has, for me, presented a new access point to a more haptic and somatic dimension of the screen I wasn’t fully aware of before.

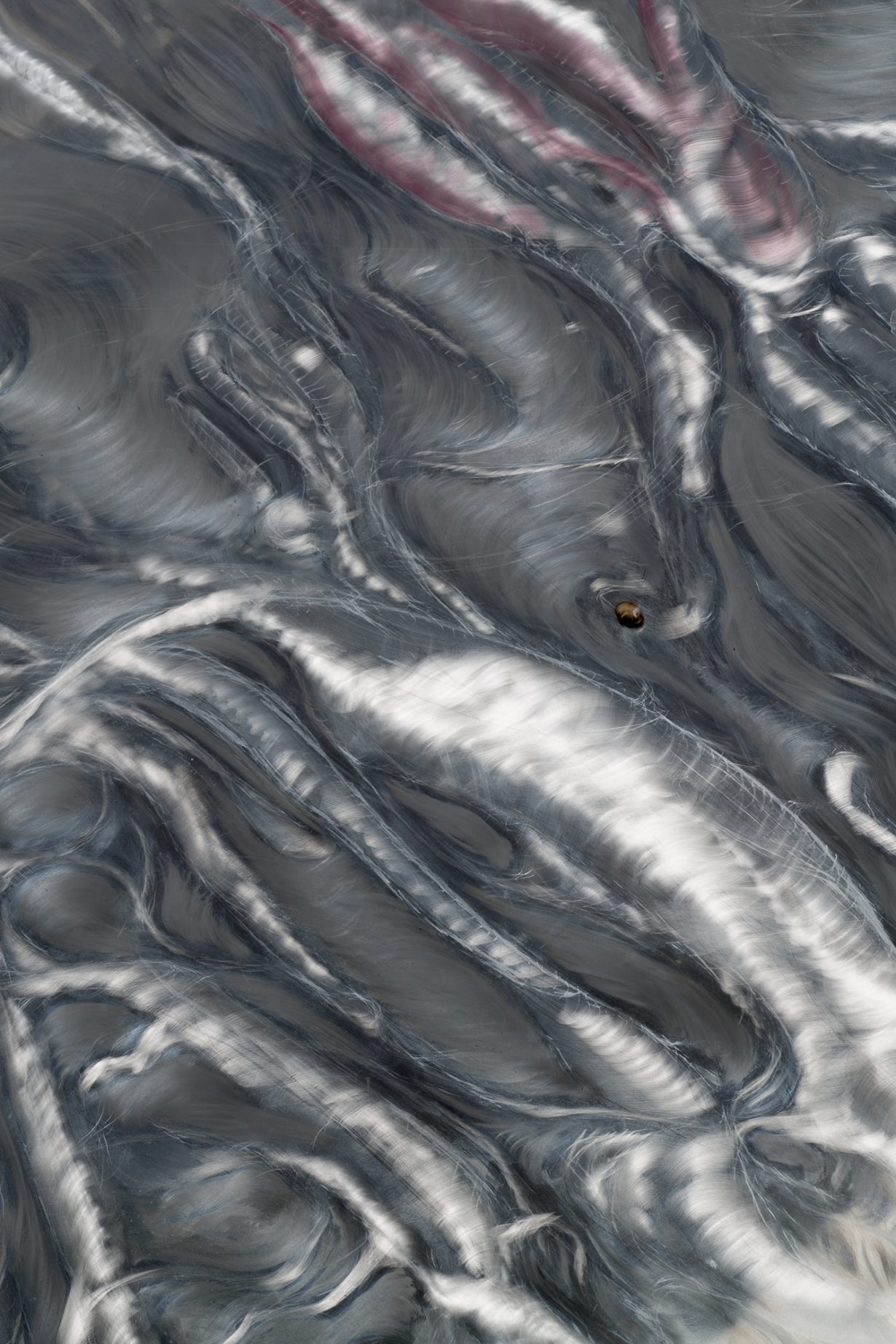

AR How did you land on aluminium as a surface?

WS The first thing I liked painting on was vellum, and I liked putting it against windows, because it was backlit like a screen. I then arrived at aluminium when I realised it has a built-in backlight. I was also doing a lot of research about the refractive indexes of different materials and how you can shift them by transforming the materials. Depending on how I scratched the aluminium, I realised I could modulate the refraction of the ‘backlight’ to varying degrees. Then by adding paint to the scratches I realised I could also reveal the latent space of the pigment itself.

AR You said even your videowork was inspired by paintings. What painters or paintings do you consider influential to your practice?

WS Many have come and gone but my longest- standing influence has been Claude Monet – every time I’m in Paris, I visit his Water Lilies at the Musée de l’Orangerie. I really relate to how he spent 30 years studying the reflective surface of the pond and its capacity to collapse so many temporalities. It’s an objective I share with both my paintings and moving-image work. I’m always looking for techniques and materials that can bind and hold the most information all at once; that can create mediated loops that collapse different simultaneous realities and temporalities.

Another early inspiration was Francis Bacon. His retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 2020 changed my life. I’ve always been so inspired by his gestural smears, how he used the materiality of paint to express not only movement but also an expanded temporality. I paint primarily with rags, so I spend a lot of time smearing. So much gets integrated in that process for me. It’s also really relaxing and makes me feel like I’m just polishing someone’s silverware.

The Dataset of Me

AR Generally speaking, what interests you about collapsing different temporalities, or as you say, creating mediated loops?

WS Coming from a video-art background, the loop was one of the early forms that really fascinated me. I didn’t fully understand why at the time, but as I kept going, the loop kept emerging. It has expressed itself in so many different ways, and now, with the paintings, it’s there again. The loop is at the centre of everything – quantum physics, AI and even trauma. More broadly, I think it’s now related to how I understand being alive – how as people we are just ever-expanding loops of information and experiences.

AR That reminds me of how the algorithm is used in the Rockbund show. It’s an open-ended loop that is updated and morphs the appearance of the show every week.

WS Exactly. And this is what led me to AI as well: AI works with datasets that you can constantly update. The program then interpolates the information and expresses where the dataset is at.

AR For the paintings that you make based off AI-generated imagery, do you always build your own datasets?

WS Yes, because I’m interested in thinking about the self as a unique dataset. I like to think about the entanglement that we have with AI, how we’re influenced by AI and how we’ve absorbed algorithms into our physical bodies. The initial source data for the AI paintings were my first five paintings, made without AI. From there it’s become an ever-expanding dataset: the more paintings I make, the more I photograph and put back into the dataset. It’s a mirroring process of the AI interpreting my marks and gestures, and then me referencing the AI’s interpretation by creating new paintings based on the images it generates. The paintings are, in a way, physical gestural expressions of the algorithms that I embody.

AR Have you learned anything about your own painting from AI?

WS In a way, AI has taught me how to paint. Traditionally, painting is a mastering of your own style, and the AI had the ability to efficiently perceive what I was doing before I even understood it.

For example, my first series of paintings was based off interior sets of The Bachelor. There was one painting that featured cut and butchered birch trees, which were props in the hotel foyer. Somehow, the AI picked up on those trees and ended up propagating this landscape that was not very present in the series. This was really interesting to me because I’ve always been deeply interested in landscape painting but didn’t have my own access point to it. Somehow the AI picked up on this and presented a landscape that I felt so deeply connected to that doesn’t actually exist. It has this otherworldly quality and is, in many ways, a landscape that only exists somewhere between me and the AI.

Monogamy Loops

AR You seem so invested in everything from art history to artificial intelligence to reality TV.

WS There are common threads throughout a lot of the subjects, even though they aren’t always apparent at first. I’ve come to understand reality TV, for example, as another mediated loop with a pretty controlled dataset.

If you watch all 27 seasons of The Bachelor, they are virtually the same but with slight adjustments to the dataset. The adjustments feed on buzzwords and current pop-cultural issues to keep both new and old audiences engaged – the tried-and-true loop of heteronormative monogamy!

AR Can you tell me about what you’re working on now?

WS I’ve been working on a new series about figures and encounters between them. They’re very far from any sort of human figuration, but as I was exploring the AI landscape, I kept coming across these amorphous entities. They are lifeforms that seem to exist between worlds, between species, between scales. The more I began studying and painting them, the more I became interested in what auras, energies or dynamics they could have between each other, and I started staging narratives with these figures in encounters. They’re experiments in trying to understand how different life entities relate to each other.

AR This reminds me of a quote from you that’s been used time and time again about your practice being ‘born out of a desire to dematerialise corporeal identity’. As a final question, how do you see and use painting as a way to manifest this desire?

WS I remember saying that in grad school and my teachers were like, ‘what are you talking about, you’re crazy’. But it came from my frustration with how inadequate it is to read someone’s body or how they present themselves as a way to understand other dimensions of the being or person. You’ll rarely see human figures in my work, because, to me, they are pretty obsolete forms in terms of their ability to communicate anything interesting. Currently, with the paintings, I’m interested in entities that can be evasive and shift. That, to me, opens another space that activates more productive strategies or techniques of perception.

Emily McDermott is a writer and editor based in Berlin