Miranda July’s Somebody (2014) is a short film in the winsome misfit mode that self-identifies as a promo for an eponymous messaging app. The film follows brightly costumed child-adults as they struggle entertainingly with emotional minutiae before turning to the Somebody app to deliver verbal messages through their choice of a third party – ‘When you can’t be there… Somebody can!’ as the strap line runs. The Somebody app exists to download in the real world, and is described by July as a kind of outsourced performance project, but it’s hard to tell how serious a proposition it is. The September edition of Wired magazine provides a handy checklist for ‘How to Build a World-Beating App’. Somebody scores high in certain areas – notably 4 (‘Develop a Brand Identity’) and 8 (‘Make it Highly Visible’) – but falls on 6 (‘Test it to Breaking Point’) and 10 (‘Grow the Right Way’).

Both Somebody the film, and Somebody the app were bankrolled by the fashion brand MiuMiu. The whole slowly-but-surely ethos of rigorous snagging, soft launches, early adopters and territory-by-territory roll out – all of which would really have benefitted Somebody, which, like Uber, needs a geographically proximate core of existing users to function – does not fit in with the fashion cycle. MiuMiu’s Autumn Winter 2014 collection, from which prominent elements of the film’s costumes were derived, was unveiled in March and arrived in stores in the late summer. Somebody, the film, was launched on 28 August at the Venice film festival, an arena that lent a kudos-like gloss to both July (as filmmaker) and MiuMiu (as patron) for the creative aspect of the project. The date also coincided neatly with the start of the fashion season: unlike most films shown at Venice, Somebody went up on Youtube almost simultaneously, so the app had to follow suit.

I didn’t have the chutzpah to go for the full ZYX random-movement experience in a public arena so outsourced the experience to a twelve-year-old travelling on the London underground

Six months to make a ten-minute film and develop a perfectly functional global-use app is not optimal. I have yet to get Somebody to work in London, even at the opening of Lisson Gallery’s Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg / Marina Abramović shows (a combination of artists I felt certain would throw out some Miranda July fans). Twitter indicates that most of the successful users (and they don’t yet appear abundant) are knocking around Brooklyn, or art institutions at which July has made a presentation. It’s glitchy, even in designated hotspots, though July has countered that the real-world-style inefficiency of the messaging service is a healthy resistance to ‘Amazonification’ – the expectation that digital interaction will be seamlessly efficient.

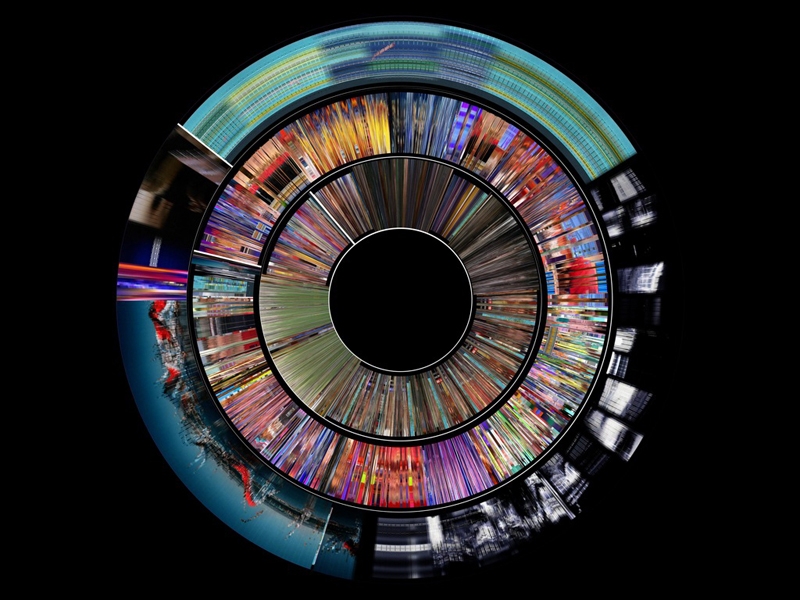

There are, of course, other artists exploring this territory, and with them a small but growing subgenre of accessible artist apps, some of which submit to ‘Amazonification’ and some of which eschew it. Since 2011 the ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe has been running the App Art Award. Recent winners include Jussi Ängeslevä, Philip Bosch, Ross Cooper & Danqing Shi’s Last Clock (£2.49) – a slick clock face graphic in which hands are represented by coiling slices of video (or live-streamed footage) which refresh each time the hand passes twelve, and Jodi’s ZYX (free), a masochistic take on Dance Dance Revolution, in which users are coerced by their iPhones to perform abstract movement sequences in public. While Last Clock has a corporation-friendly slickness (personalised editions of the work can be commissioned to hook up to streaming footage of a specified locations) ZYX is pleasingly bonkers. I didn’t have the chutzpah to go for the full ZYX random-movement experience in a public arena so outsourced the experience to a twelve-year-old travelling on the London underground. The fruits are two-fold – an ad hoc dance/performance work and filmed footage of the same capture by the phone, which is essentially dictating its own camera angles as part of the performance. The twelve year old followed the app’s instructions without question – taking orders from machines being, apparently, a millennial commonplace.

How irresistible would it be to command friends, via Somebody, to deliver thusly: ‘Calvin? It’s me Sean. I think you’re a douche [action: give wedgie] l8trs looza!’

Current artist-made apps divide fairly neatly between those in which an artist has co-opted the medium to comment on the social and behavioural impact of digital technology – such as ZYX (which riffs on public acceptance of otherwise peculiar smartphone-related behaviour) and Somebody (which seeks human contact in an online era) as well as Amalia Ulman’s app for ephemeral, unattributed communication Ethera (free, though currently down) – and polished design-based apps created by digital studios such as Field’s Energy Flow (free) a randomised non-linear film sequence of hypnotic swooshing microlandscapes (it seems to be popular with stoners and insomniacs), and Universal Everything’s Together (free) – an app that crowd-sources animation sequences – first shown as part of the Barbican’s Digital Revolution (2014) and now online. Together, with its easy to use animation software, again has strong appeal for the millennial generation, neatly answering the question of why artists would consider the app as a medium at all – this IS their medium. Indeed I’m quite tempted to subvert Somebody’s child-adult hipsteria by introducing it to actual children in London playgrounds. How irresistible would it be to command friends, via Somebody, to deliver thusly: ‘Calvin? It’s me Sean. I think you’re a douche [action: give wedgie] l8trs looza!’

Both Field and Universal Everything have created editions for digital art entrepreneurs Sedition, though these are not works of the interactive, generative flavour that characterise their apps. While Ashley Wong, Sedition’s Head of Programmes and Operations says that apps interest them greatly, they are problematic for the retailer’s ‘Anytime. Any screen. Anywhere’ ethos. Sedition hold users’ digital artworks in a ‘vault’, from which they can be accessed on any connected device – any artist-created app would have to work across multiple platforms, which currently makes it too technically demanding to countenance.

In 2011 curator Grainne Sweeney and Katherine Pearson, the managing director of Flo-culture, founded Apps By Artists Ltd. It’s a testament to the inherent complications of the app as a medium that, despite ongoing projects with artists including Rose English, Joan Tatham & Tom O’Sullivan and Liliane Lijn, they don’t expect to release their first app until mid 2015. Sweeney’s principle interest as a curator to date has been in identifying the right makers to work with artists. While historically this has involved craftspeople in the fields of silver or glass: now she’s matchmaking artists with software developers.

For artists and producers battling Apple vs Android favouritism, constantly evolving technology and the niggling question of how to monetize non-popularist app artworks in a marketplace where the dominant business model is to sell large volumes at low prices, it is perhaps worth bearing in mind the let’s-get-this product-out-the-door mantra attributed to Steve Jobs from the early years of Apple: ‘Real artists ship’.

Online exclusive first published 30 September 2014