A new show at Le Bal in Paris connects the photographers Donna Gottschalk and Carla Williams, across decades, to find a better way of representing queer communities

“I wanted my people to be remembered, if only by me”, we hear photographer Donna Gottschalk say in the film projected on the ground floor of Le Bal. Now in her seventies, she speaks as her own photographs and negatives appear on the screen, portraying young women posing in groups, hanging out or embracing on rooftops, or in interior settings. Her voice is tender, matter-of-fact, occasionally heavy with loss as she recalls her friends and lovers – Jill, Marlene, Chris, Oak, Binky, her sister Myla, Sally and others – all lesbians who like her were living at the margins. “I treasured my friends,” she says, “life was so interesting among them.” The film, directed by writer and art historian Hélène Giannechini, sets the tone for the exhibition: not so much a retrospective for the photographer as a dialogue, a long conversation across time between Gottschalk and Giannechini. Their exchange – part interview, part meditation on friendship, loss, and survival in queer communities – underpins everything that follows.

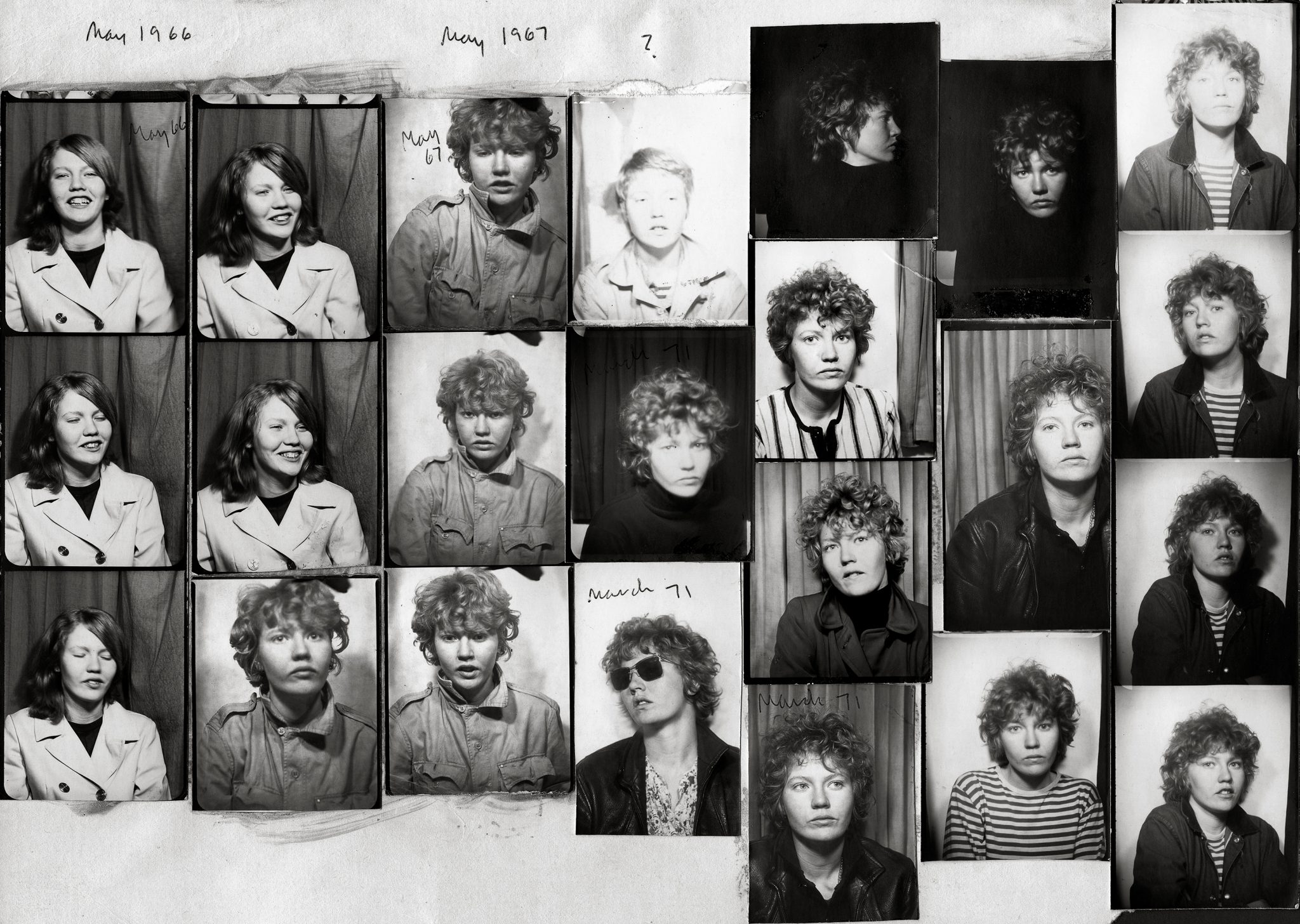

Descending to the lower floor, the mostly black-and-white, small-format photographs taken between the late 1960s and mid-1970s unfold like a photo album of sorts, presented in clusters of three to five images hung at eye level. A series of diaristic wall texts by Giannechini punctuate this display, in which the author moves between Gottschalk’s past and the present of their encounter in New York some 50 years later, folding history into intimacy. We start in New York, where Gottschalk grew up in a tenement on the Lower East Side, taking her first pictures of members of her family at her mum’s beauty salon. During her photography studies at the Cooper Union, she turned her lens to her friends and lovers, and all the lost youth that came to seek shelter at her flat. Not that she ever made a living from photography – she supported herself and her friends through a string of odd jobs, from cashier to nude model to driving around tourists in horse drawn carriages in Central Park. In one picture, we see four women sleeping on mattresses on the floor, two of them embracing each other, while a child sleeps on a bed to their right. It looks like there’s daylight coming from outside, the rays sculpting the folds of the blankets and the surrounding mess; they look like one big lesbian raft, adrift together.

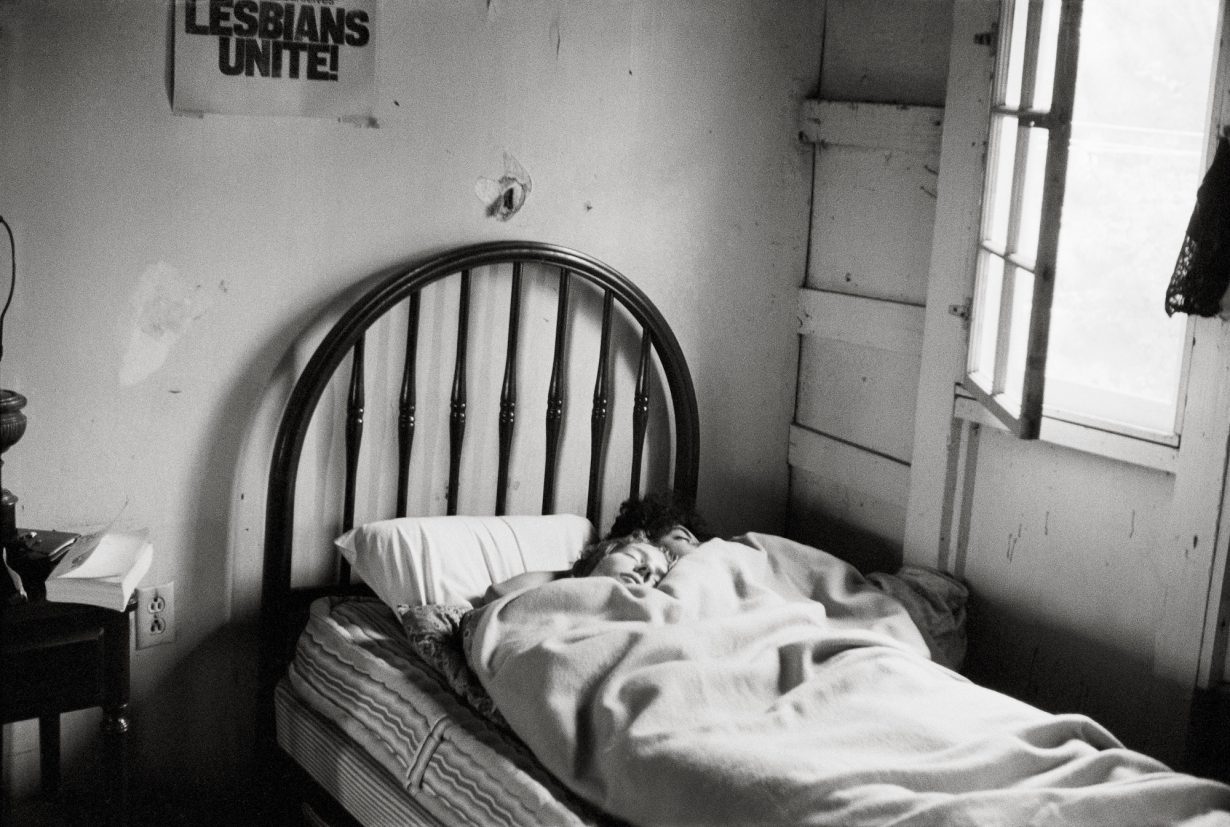

Gottschalk’s work is inextricably tied to her activism in the fight for gay, lesbian and trans rights during the late 1960s. She became involved with the Gay Liberation Front at the age of seventeen, in the aftermath of Stonewall, and later on organised actions with radical lesbian groups. But this political atmosphere only seeps into her pictures obliquely: a Lesbian Unite poster glimpsed on a wall, a flyer in the corner of a frame. One exception is the shocking closeup of Myla’s face after a transphobic attack, her eyes shut and face swollen. Gottschalk seems less moved by a desire to create symbols of liberation than by the urge to prolong her friends and lovers’ existences through photography – like a quiet, sustained ritual.

In one of her photographs from 1969, five of her ‘baby dike’ friends pose on the fire escape outside her apartment at night. They’re wearing polos and T-shirts, grinning, defiant, all attitude. Behind them stretch the red-brick walls of Lower Manhattan, fire escapes twisting upward; to the right, the window of Gottschalk’s flat frames the scene. From below, a bright, mysterious light cuts through the dark, casting them in a sort of dramatic chiaroscuro – a cool, theatre-like staging of lesbianism and sisterhood. Like many of her portraits, it conveys an irrepressible joy and togetherness – that us-against-the-world confidence that comes from love and friendship in the face of adversity.

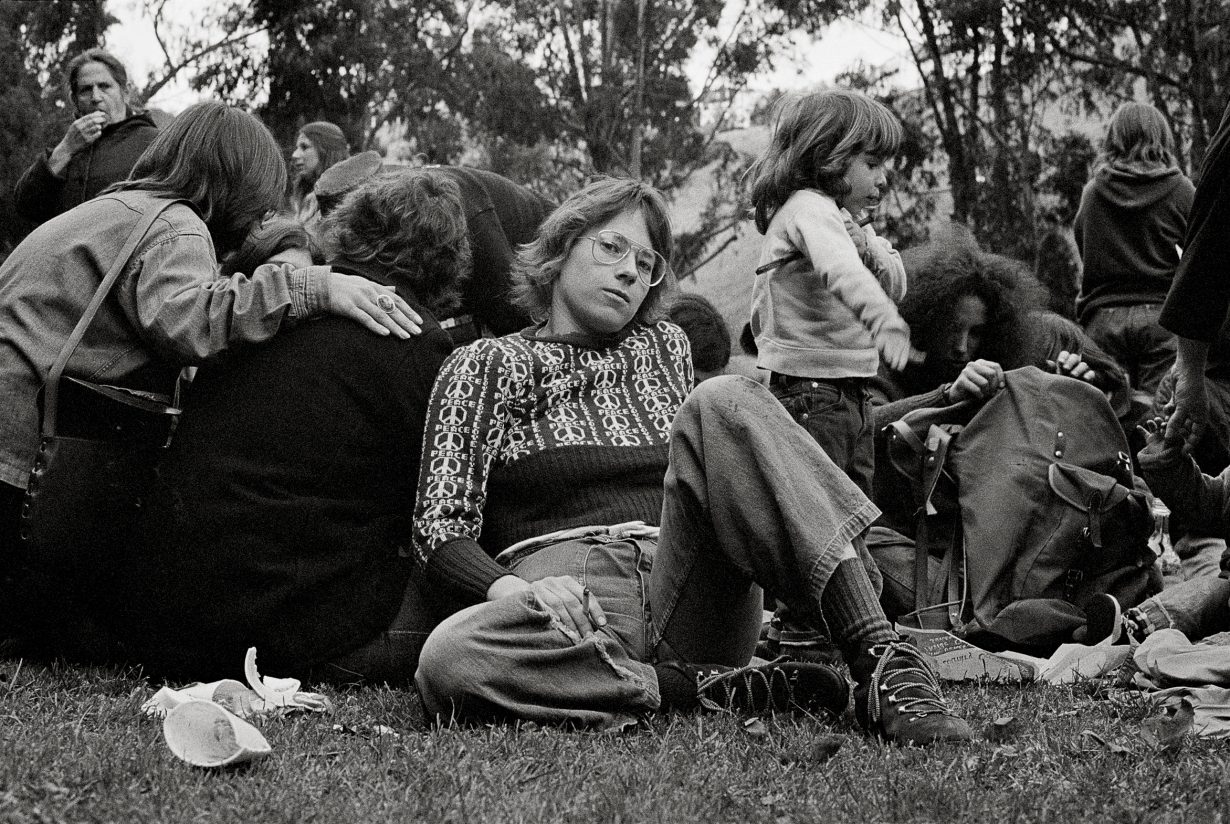

A few years later, in the mid-1970s, Gottschalk moved west, joining friends in San Francisco and visiting lesbian separatist communities in Oregon and California – part of the ‘Back to the Land’ movement that sought to live beyond patriarchal structures. Here the atmosphere shifts, the light changes: she captures women outdoors, in parks or in fields, playing baseball, straddling each other in broad daylight. There’s a rare colour photograph of two women in denim, one of them sitting inside a trolley, all country queer with her hat and red bandana tied around her neck. In another black-and-white image, Donna reclines odalisque-like on the bed of a log cabin, a candleholder protruding from the wooden wall behind her, the condensation on the window blurring the mountainous landscape outside and conjuring a certain heat. She looks straight into the camera – confident, sexy, utterly at ease.

There are only a handful of images dated after 1976, after she returns to New York – the camera moves back inside, notably with a few nude portraits shot against a striped wallpaper, and a picture of Myla, now in her fifties, looking worn out – and they feel grim in comparison, drained of light and friends. So Giannechini’s voice takes over, acknowledging some of the gaps in Donna’s story, while attempting to fill in others: ‘She organized her own disappearance, escaping first to Connecticut, then to Vermont. She gave up the idea of exhibiting her photographs.’

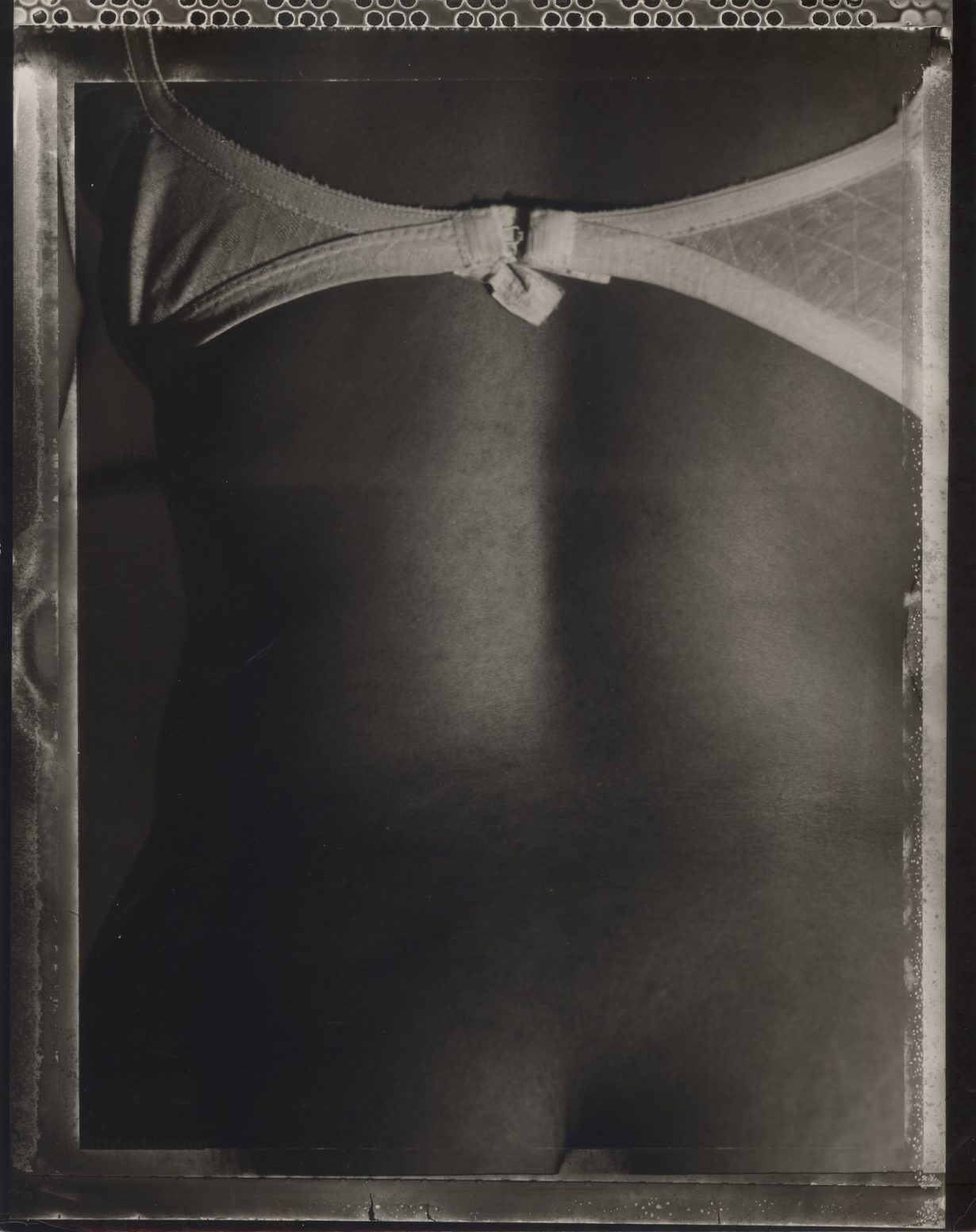

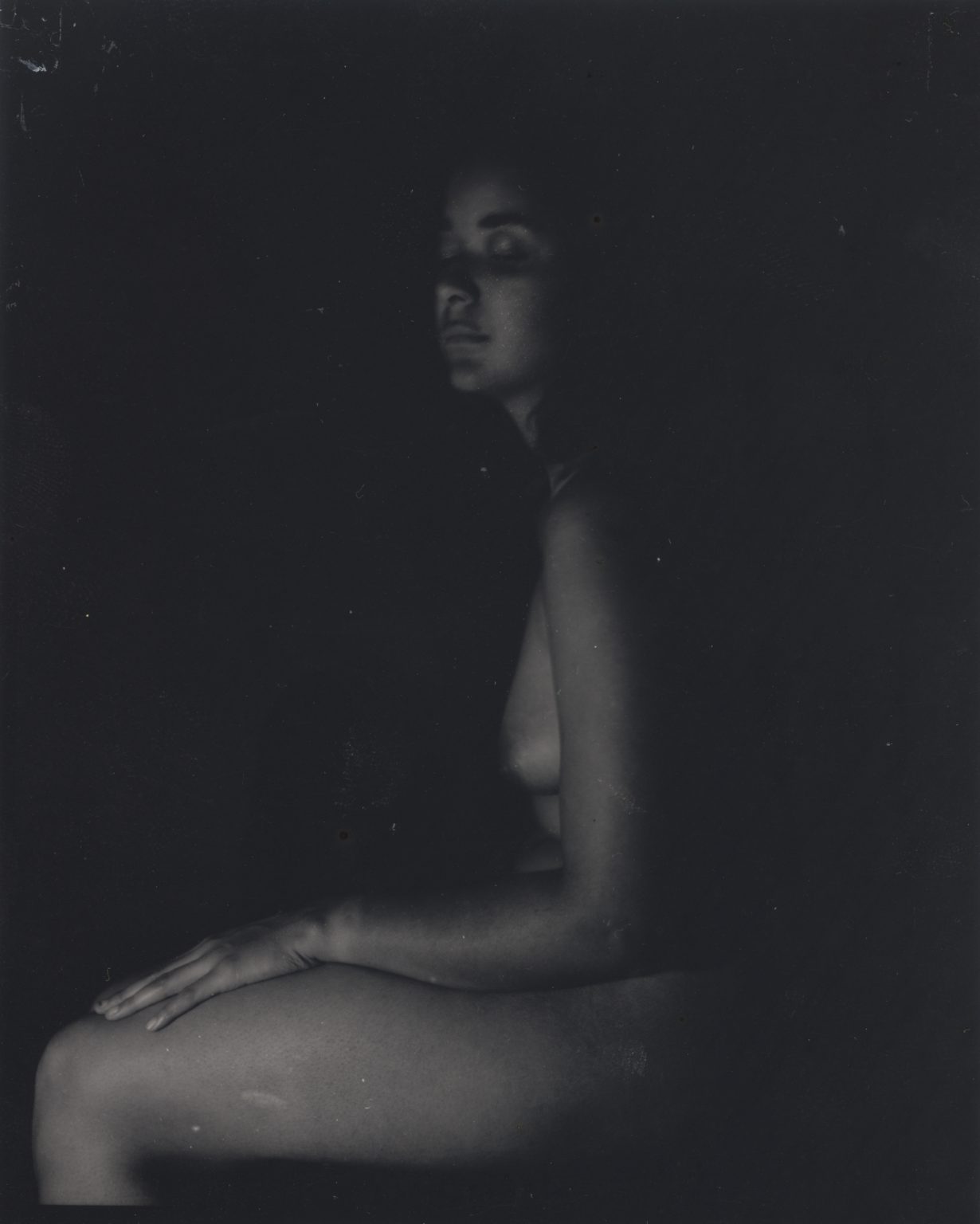

Back upstairs, a small display of photographs from Carla Williams’s series Tender (1984–1999) resonates like a soft echo of Gottschalk’s photographic gesture. Here, Williams turns the camera on her own naked body to create small black-and-white self-portraits; the images are soft, the poses intimate, with each shot feeling like a caress. Placed as a bookend to Gottschalk’s work, Tender bridges generations and, while doing so, foregrounds self-representation, and more specifically, the desire to rectify the lack of black, queer, female bodies in cultural representation during those decades. Connecting these two bodies of work is an iconic black-and-white photograph by Diana Davies, in which Gottschalk is seen at the 1969 Stonewall anniversary protest holding a placard that reads: ‘I am your worst nightmare, I am your best fantasy’. Williams explains in the exhibition text that she kept a copy of that picture as part of her own archive for years, not knowing who the woman in that picture was until Gottschalk’s work was shown for the first time in 2017 at the Leslie Lohman Museum in New York.

It is in those echoes that the work and stories of Gottschalk, Giannechini and Williams come together. Instead of presenting a nostalgic or historiographic perspective, We Others reads like a living lesbian archive, animated by friendship, dialogue and the transmission of those stories and images from the margins. It is a reminder that queer representation is a collective, relational practice, inseparable from the networks of care and collaboration that make the creation, circulation and visibility of such images possible. In her final wall text, Giannechini concludes: ‘it occurs to me that, (…) in these unpredictable times, collecting Donna’s photographs, piecing together her story, and letting it seep into my being is one of the most appropriate and comforting things I can do.’

We Others: Donna Gottschalk, Hélène Giannechini with Carla Williams at Le Bal, Paris, through 16 November

Louise Darblay is a freelance writer and was formerly Managing Editor at ArtReview