The Apsáalooke artist on trauma, healing, and the reclamation of oppressed cultures – as told to ArtReview’s Fi Churchman

The Crow Fair [held in Montana each August] was officially established in 1904, organised by Indian agent Samuel G. Reynolds, a white US government worker who resided on the Apsáalooke (Crow) reservation. In its attempts to restrict the Apsáalooke nomadic way of life, the government wanted all native people to assimilate into US society; one of the ways was to introduce farming as a means of self-sufficiency, but also to prevent the movement of the Apsáalooke. Reynolds began to organise an event based on the popular format of a county fair – in which local people would bring their harvest and cattle, their prize animals and crafts. Knowing that this alone would not encourage participation from the Apsáalooke community, Reynolds suggested incorporating elements of native culture. One of those activities became the parade that takes place each morning, symbolising the movement to a new camp and recalling a time when the Apsáalooke were able to move across the Plains.

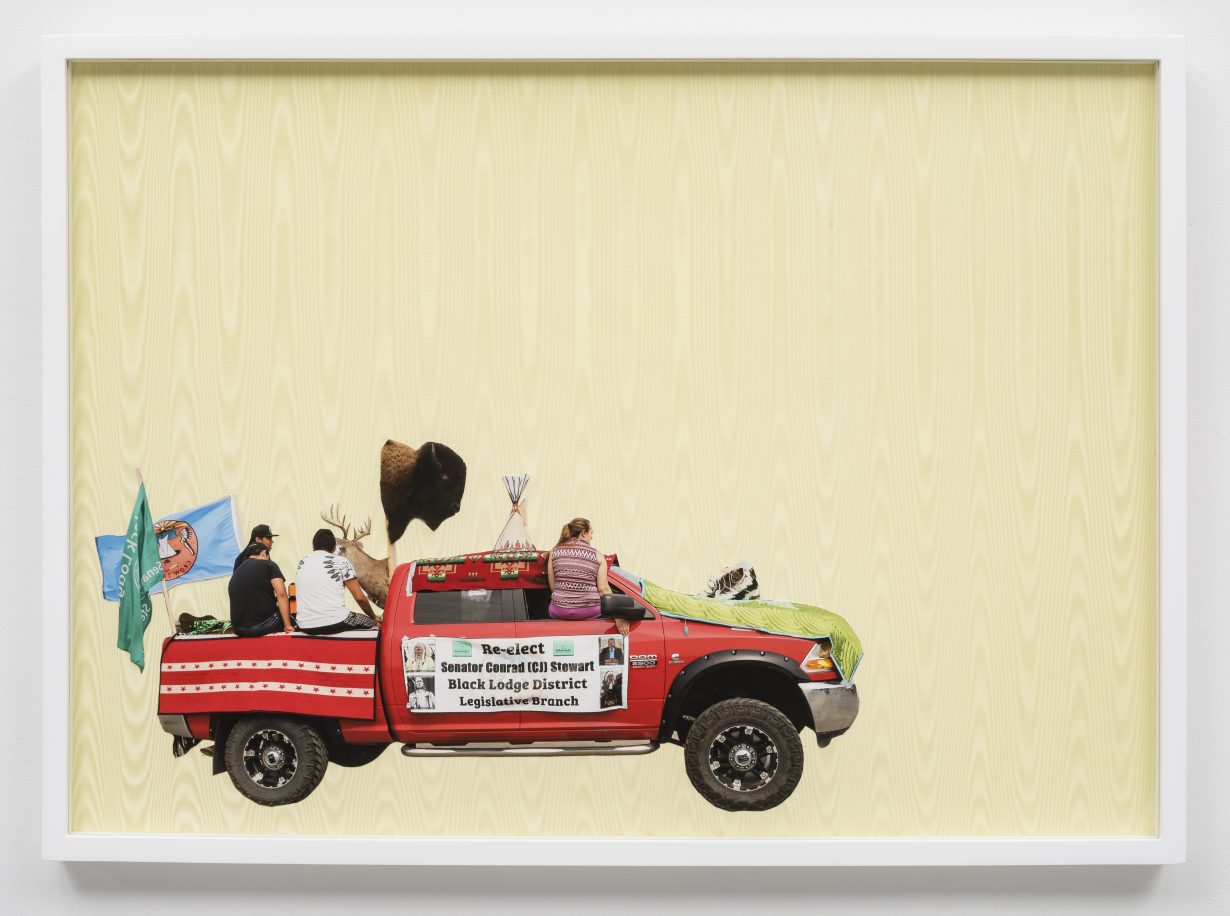

One very important aspect of the Crow community is that no one person can brag about themselves. Each of the pictured vehicles represents a family and there are clues within every float that tell you about who this family is, like maps of identity. You might notice the banner pitching for the reelection of Senator Conrad Stewart for Black Rock District? He’s not in that vehicle, but that’s his family, who are parading on his behalf. It’s like a loophole, so even if you can’t elevate yourself, your family or your clan can do that for you.

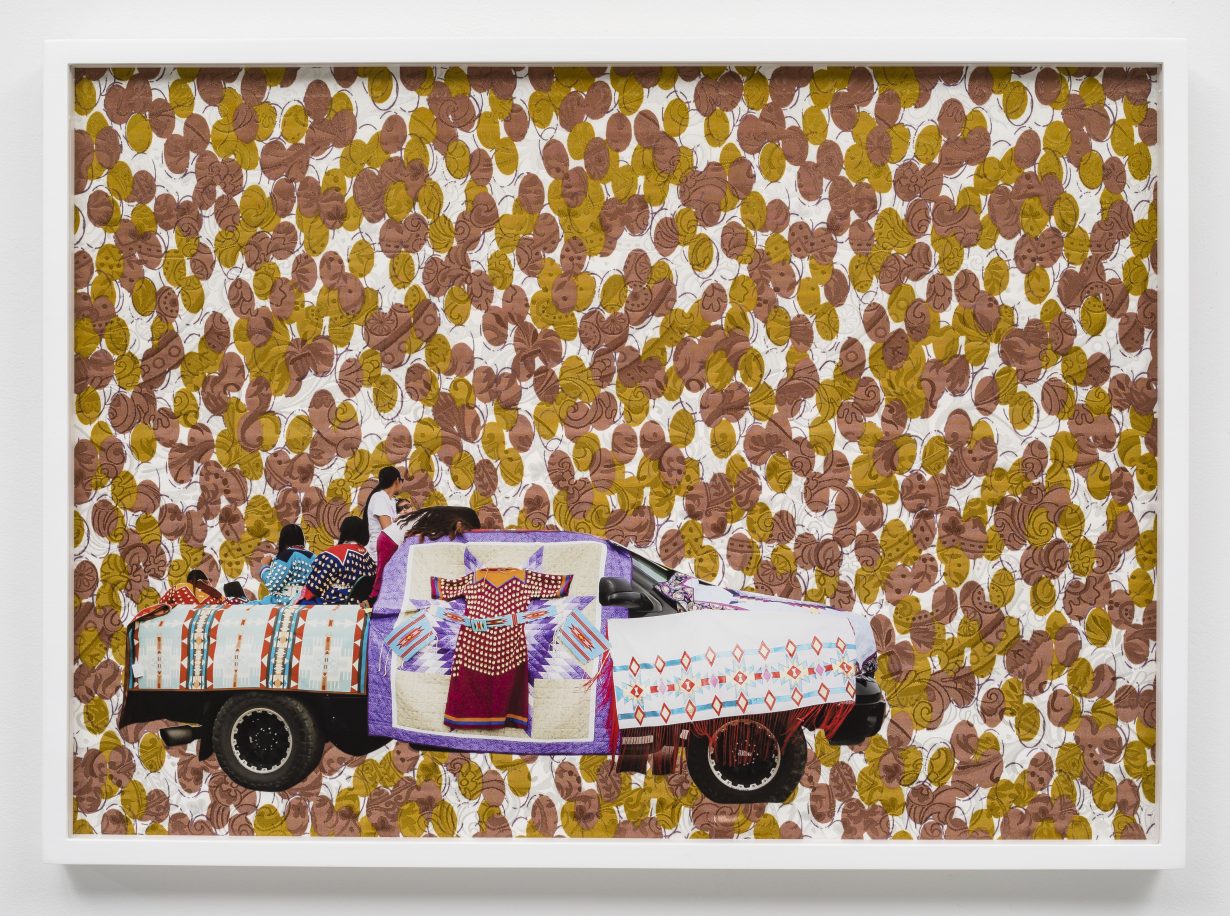

The one with the war bonnet, Hawate (One), is my family’s float. The bonnet was made by my grand-uncle Clive Francis Dust, Sr [whose Apsáalooke name was Baahinnaachísh], to represent the Red Star family; he was always coming up with ideas for us to create things that could be utilised in the parade (all of my grandma’s handmade shawls are up there, too – she was an amazing maker). It’s not just a float that people are sitting on, but a way of recognising the importance of family.

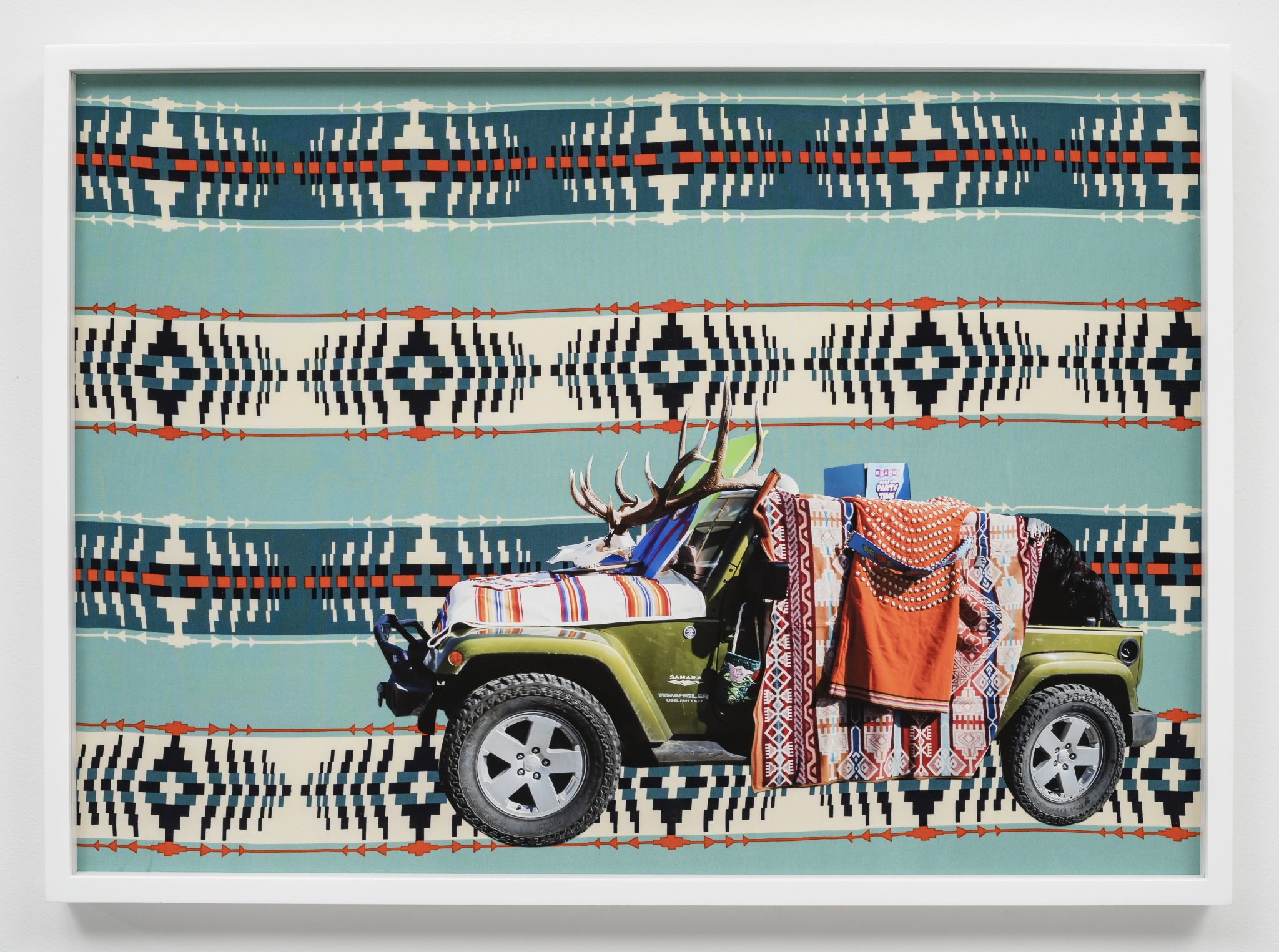

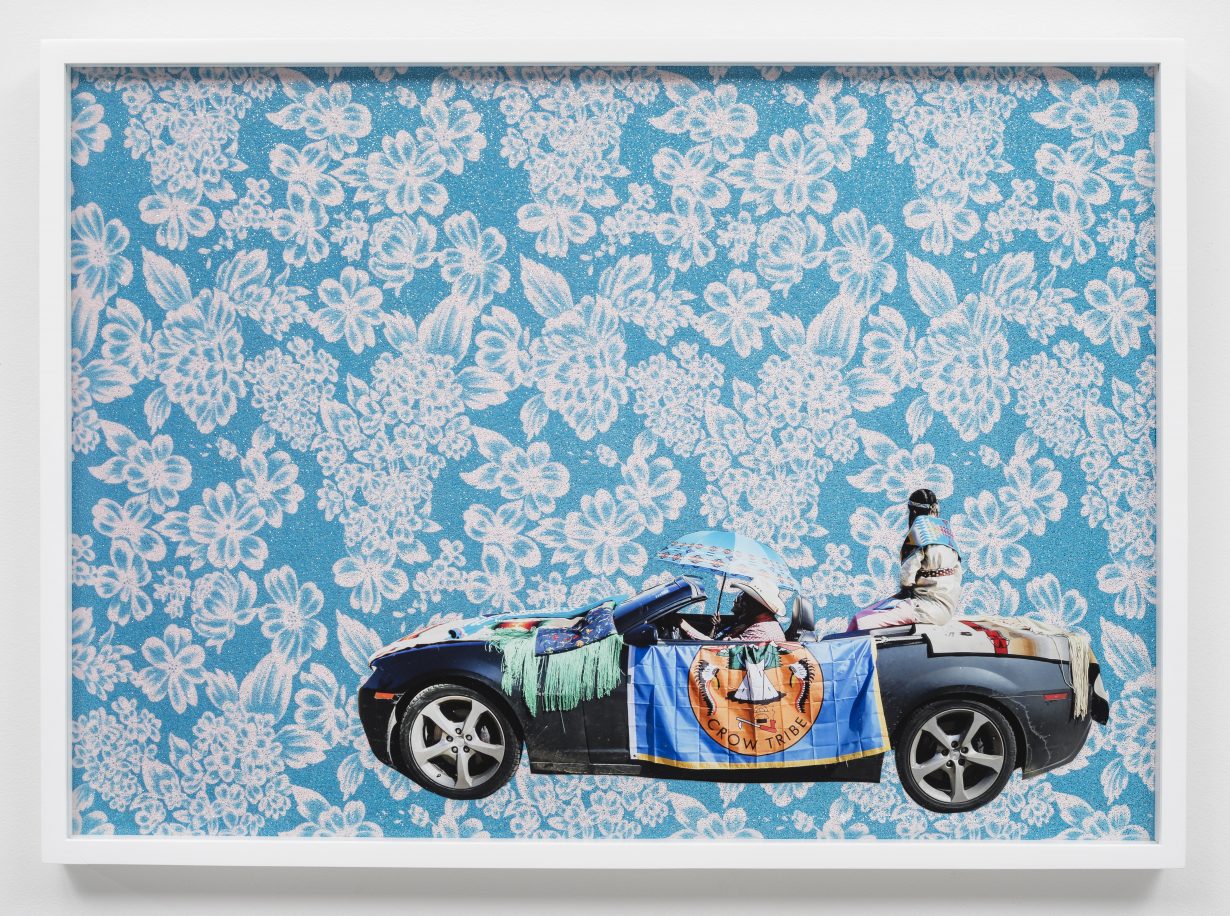

A lot of the time, people outside of the culture who want to see the ‘authentic’ native person are really wowed by the sight of native people on horses. But for me, growing up, I would get such a kick out of seeing these cars that are fully adapted into floats, dressed up with pride and which represent each of our families. Now I see that these parade vehicles are really indicative of the resilience of our culture; they’ve become a symbol of subverting that attempt to make the Apsáalooke assimilate, as well as a challenge to the ‘American’ identity that’s so bound up with car culture here.

One of the beautiful things about Crow Fair is its intense vibration and total saturation of overwhelming colour. A professor at art school once told me I used too much colour. But these are the colours I grew up in, and that I’m accustomed to. The vehicles are adorned with richly patterned blankets, quilts and traditional regalia – including elk-tooth dresses [Axpichiaxxo (Fifteen)]. The regalia is usually made from wool, which is hot and itchy, so a lot of the time people will be wearing softer satin fabrics beneath. It’s these fabrics that form the backgrounds of A Float for the Future. Incorporating both the outer regalia and the clothes underneath is a way of acknowledging the identity of the Apsáalooke people, not just in terms of how we celebrate publicly, but also, in some ways, it’s a window into what’s normally hidden or less visible; our public and private selves are set side-by-side. And that idea of visibility is important, not only in terms of material culture, but of language too. The Apsáalooke language is at threat of becoming extinct. So I try to create bodies of work that include the language, whether it’s incorporating the names of Crow figures into titles, in 1880 Crow Peace Delegation (2014), or in the practical use of numbering the series for A Float for the Future. Part of my work is about calling up the language to preserve it in some way.

Crow Fair is now a cultural revival and a way for us to fully immerse into the Apsáalooke culture and be proud of it, to share and teach our future generations what it means to have this heritage. In order to move forward and maintain the culture, we need to have access to the materials that institutions across the country and even in Europe have in their holdings. That needs to be poured back into the community where it belongs, so that we can reunite and reeducate ourselves about who we are as a people. So that we can reunite with our history.

Wendy Red Star: Delegation was published by Aperture Monograph in May 2022. An exhibition of Wendy Red Star’s work, American Progress, is on view in the Anderson Collection at Stanford University, Stanford, through 28 August