Enter the Shanghai-based collective’s interactive shows, hosted in dystopian amalgamations of well-known cities, in oceanic abysses, on roller coasters and desert islands

COVID-19 has instigated an onslaught of online initiatives that have saturated the digital artworld with fairs, exhibitions, social-media campaigns and educational programming, in an attempt to play catchup to a now overwhelmingly online industry. While many institutions have scrambled to repackage their programming, others have taken this opportunity to build new models for exhibition-making and new means for connecting with audiences at a distance. Prior to the pandemic, in China, apart from ongoing projects like Rhizome (a pioneering nonprofit dedicated to new media art), few endeavours have put forward serious efforts to cater to digital art hosted in its native environment – a void artists are, and have been, looking to fill.

Courtesy the artists

Shanghai-based artist collective Slime Engine, or 史莱姆引擎, has been utilising digital space since 2017 with different projects that manipulate the user’s understanding of physical space, possibility of place when it comes to exhibition-making and participatory expectations for art-seekers on and offline, in a practice that is ‘as flexible as “slime” and as inclusive as a “search engine”’. Hosted in dystopian amalgamations of well-known cities, in oceanic abysses, on roller coasters and desert islands, their interactive shows assume gamelike features that stand in stark contrast to the traditional white-cube model adopted by many galleries and museums. Founded by four photography students – Li Hanwei, Liu Shuzhen, Fang Yang and Shan Liang – Slime Engine treats the internet not as a replacement for physical institutions, but as a platform with properties specific to digital and virtual media that would be nearly impossible to replicate in the ‘real world’. Although that’s not exactly how they see it.

“We don’t think too much when designing exhibition spaces,” the collective tells me over an array of WeChat messages, Instagram DMs and emails. “Many people might think we’re creating a space, but for us, these spatial forms have already been integrated into our vision.” Over the last two decades, China has become home to the world’s fastest-growing movie-industry. Coupled with that, lax copyright enforcement has seen scores of pirated Hollywood films flood streaming websites like Youku, making the twenty-something-year-old artists of Slime Engine part of an internationally minded generation growing up with an intense exposure to special effects. “It wasn’t so much a space we created, but material we chose to use.”

Courtesy the artist

Their work has undeniably drawn from the cinematic canon, with dystopian landscapes and sterile futuristic-looking manufacturing or testing labs often featured. Immersive, unsettling and uncomfortably familiar, the flawless figures and facial features are just distant enough in likeness, but similar enough in content to imagine a Black Mirroresque narrative that could easily be our reality. It’s worth remembering that in 2018 international media cried wolf when the PRC introduced its Zhima social-credit system, comparing it unequivocally to the third series’ episode ‘Nosedive’ and announcing the actualisation of creator Charlie Brooker’s vision in China. Despite the inclination to insert their work into a surveillance-state-fearing, nationalist, too-close-to-home critique of collective social behaviour and government intervention, these narratives sit barely adjacent to Slime Engine’s embodiment of a globally felt anxiety.

Take their recent work Headlines (2020), shown at We=Link: Ten Easy Pieces in March, as part of an open-call exhibition initiated by Chronus Art Center, Shanghai, Rhizome and the New Museum, New York. Comprising lifestyle articles, opinion editorials and news coverage, the text and moving-image work catalogues the various ways the ‘novel hookvirus’ is disrupting the global order. With quotes from ‘Chaos, director of the Institute of Interstellar Business at the University of International Business and Economics’ and other fictional figures (including government officials), the editorials expound on the positive economic effects of the pandemic and urge the public not to give in to political conspiracies: moving offline has caused an increase in productivity, with people on average working between 12 and 24 hours a day; ordering takeout and watching TikTok have become the most popular mobile activities; while the ‘US-initiated trade war with China’ gets a brief mention, so does the assassination of a top Nezarim military commander by the United Federation of Planets.

Courtesy the artist

The work parodies media and broadcasting institutions, overwhelming concerns about the financial side-effects of a deadly virus with feelgood content like ‘New century fat-reducing rave gymnastics’ where viewers can watch a five-minute video of an anime-style young woman in a very small bikini robotically perform fractured cardio in her living-room-turned-home-gym. Headlines simultaneously visualises shadows of what is, in a world that could be, through a reformatted newspaper that encourages user engagement and activity – all the while presenting us with characters that react but don’t respond.

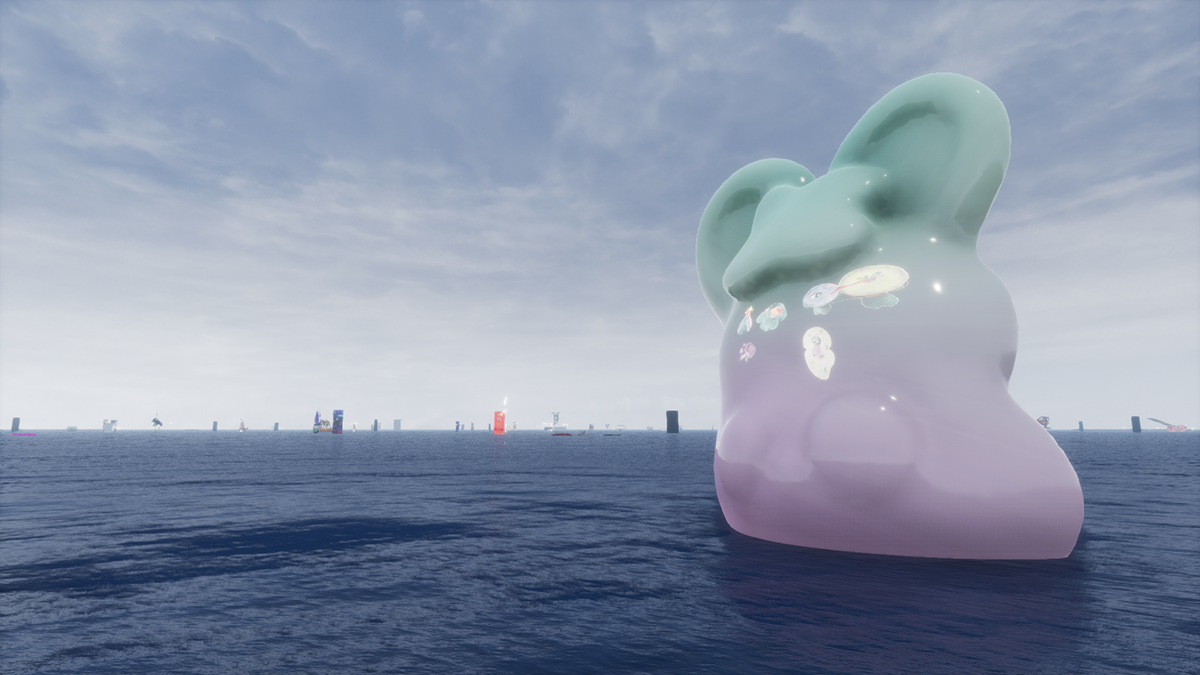

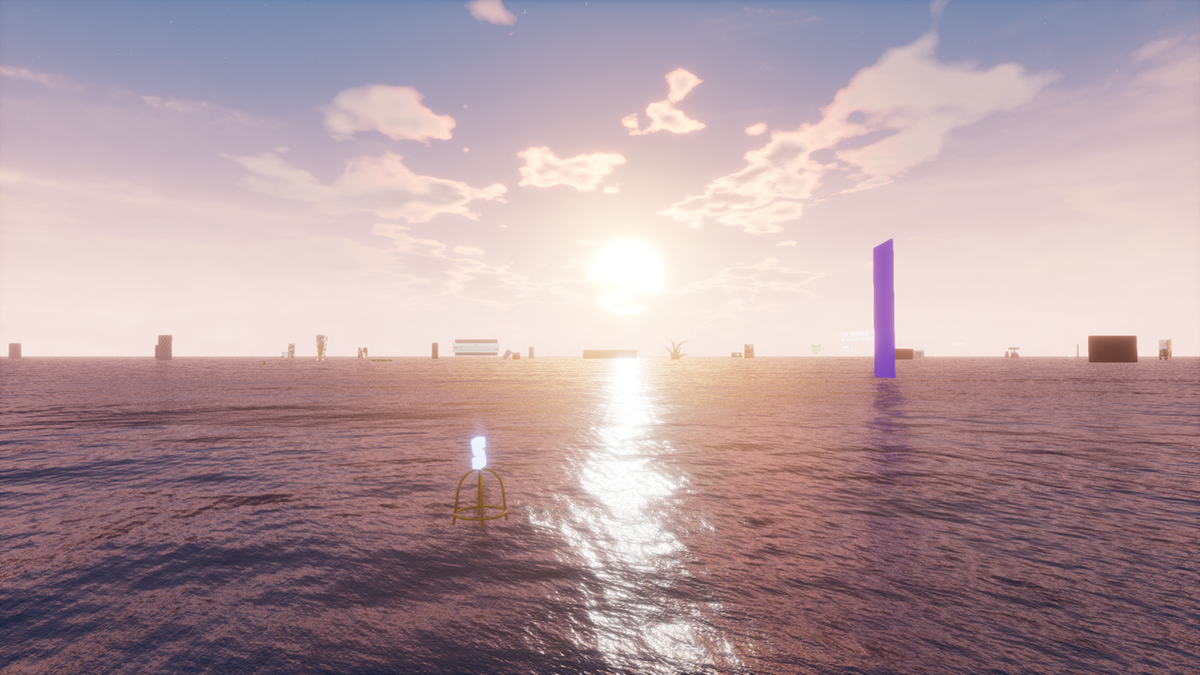

Slime Engine’s 2019 online/offline exhibition Ocean demands a different kind of user engagement, resembling a videogame more than any exhibition you’re likely to find in a museum or gallery. Although it is available for access on their website, I prefer the downloadable version of the program, which enables you to have the exhibition at hand without internet access, at anytime. Surely not what Nicolas Bourriaud had in mind when he coined the term ‘relational aesthetics’: the user has no direct contact with any art ‘object’, so to speak; instead the work’s interactivity and closeness are mediated through keyboards and mouse pads. The collective functions as the curator, while the individual members of Slime Engine exhibit their own works as participating artists in the 103-person group show. Upon loading, the program deposits you in the middle of an endless, virtual oceanic plane surrounded by artworks hovering just above the water. But the computer installation enables the viewer to move between the videos, digital sculptures and photographs via keyboard control, activating time-based works only when in close proximity to them. You get the sense that it exists both for you, and entirely independent of you.

Without instructions, its navigation isn’t necessarily intuitive. You can stand in the middle of the works or direct your point of view so that you only see sky, marked by an accelerated version of solar time. When the light changes, so does the presentation of the works, some bearing reflective surfaces while others are matt. In some ways, it’s incredibly transparent: these effects highlight what in many exhibitions is fixed and controlled – light levels, pathways, proximity to art objects and access to information. For those not already primed to critique the white-cube model or imposed curatorial narratives, it lays bare what has been heavily institutionalised for decades: the exhibition emphasises the body in relation to the art, not by pretending to walk users through the works or present them with a ‘right’ way of viewing, but simply by creating an opportunity and environment to explore.

“Ocean marked a shift for us, where since then, we’ve organised everything systematically,” Slime Engine tells me. “Every new project since then emphasises creative sustainability, and we are gradually establishing a community for young artists.” Their roster runs a wide and impressive gamut, with Ocean featuring artists like photographer Pixy Liao, musician and multidisciplinary artist 33EMYBW and internet artist ChillChill among the many, many others. Their collaborative efforts extend beyond the internet to projects with the Shanghai club ALL and group-oriented public works made with their representing gallery MadeIn. “We’ve found through organising these exhibitions that more and more public spaces have a demand for images and digital content, and that’s why bringing our creativity to commercial projects is a subject of interest for us.” Having recently shown a version of Ocean in Shanghai’s new Theatre X mall as part of the group show Wild Cinema (2020, copresented by the Art021 art fair’s sister organisation Immersive Art Gallery), the collective positioned itself between the uncommodifiable and the commercial – with neither Ocean nor any of the exhibiting works for sale through the project – further complicating existing artworld binaries tied to value and production. Their second series of Headlines took a similar form, and launched late September as part of a group show at Shanghai Plaza, a mall just a short jaunt from People’s Square. Running through the end of November, a large screen spanning three floors displays a reel of simulated newsroom interviews, product manufacturing lines and lottery balls falling in fields of digitised flowers. Shown alongside the works of Xu Zhen, Lu Pingyuan, individual member of the collective Shan Liang and many more, the work of Slime Engine is once again one of the only things in the mall money can’t buy.

Despite the radical consequences and opportunities for institutional critique that come with gamifying their exhibitions, Slime Engine doesn’t hold strong beliefs when it comes to the state of the artworld. “The artworld is already sufficient. We don’t think it’s short of anything,” they write. “We just felt the physical exhibitions people were doing were average.” Still, they’re optimistic about the increasing shift towards institutions infiltrating the digital, and what it means for how their practice and networks develop. “At the beginning of this year, some museums in China invited us to lecture internally about online exhibitioning, the advantages and disadvantages of online exhibitions increasing after the epidemic. We’re excited about it.” New technological infrastructure will enable them to implement projects they previously couldn’t, presenting opportunities for further growth and reach in a field that has long needed the change: the arts. What it means for their upcoming show Ocean 2 in November is unclear just yet, but it’s not a leap to conclude that their unintentional rewiring of art networks on- and offline will continue to be something we’re excited about.

Sarah Forman is a writer based in London