A collectively authored text about the promises and shortcomings of feminist exhibitions

Finally, feminist art is being celebrated by institutions in the UK. Sixteen years after a series of blockbuster feminist exhibitions in North America and Europe in 2007, three major group exhibitions have recently opened: Women in Revolt at Tate Britain; Re/Sisters at the Barbican Art Gallery; and Ridykeulous: Ridykes’ Cavern of Fine Inverted Wines and Deviant Videos at Nottingham Contemporary. Elsewhere, Marina Abramovic’s monographic survey is touted as the ‘first solo show by a woman artist’ at the main gallery of the Royal Academy.

Given the widespread neglect of the women’s art movement in UK institutions, we approached these exhibitions with a degree of scepticism. We wondered if the shows would be tokenistic gestures of inclusion, designed to compensate for decades of exclusion; if they would feel nostalgic and retro-chic; or manage to convey the urgency of the struggles explored. Fundamentally, we wondered how their curators could enact feminist tactics and values, in form as well as content.

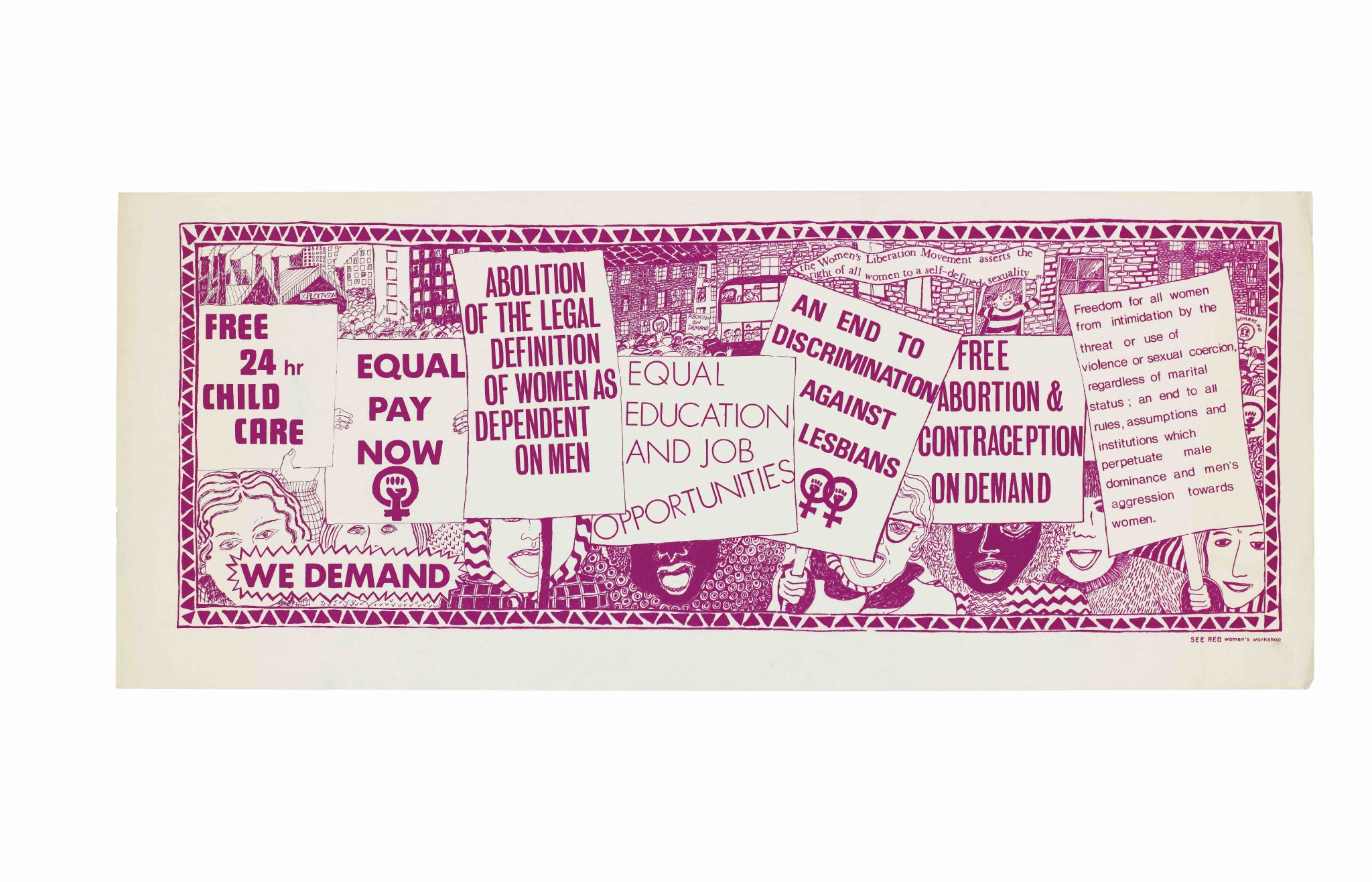

Those of us who were part of the second-wave women’s movement feared Women in Revolt – which covers two decades of art and cultural activity, from 1970 to 1990 – would be another exhibition reproducing feminism’s whiteness, ableism and middle-class orientation. Instead, we were thrilled to see many long-forgotten or ignored individuals and groups. Women in Revolt broadens the feminist canon in the UK in terms of the artists included, the diversity of artistic approaches and the inclusion of archival materials often undervalued by institutions, such as magazines like Spare Rib and Shrew, fliers from women’s centres and posters by the See Red Women’s Workshop.

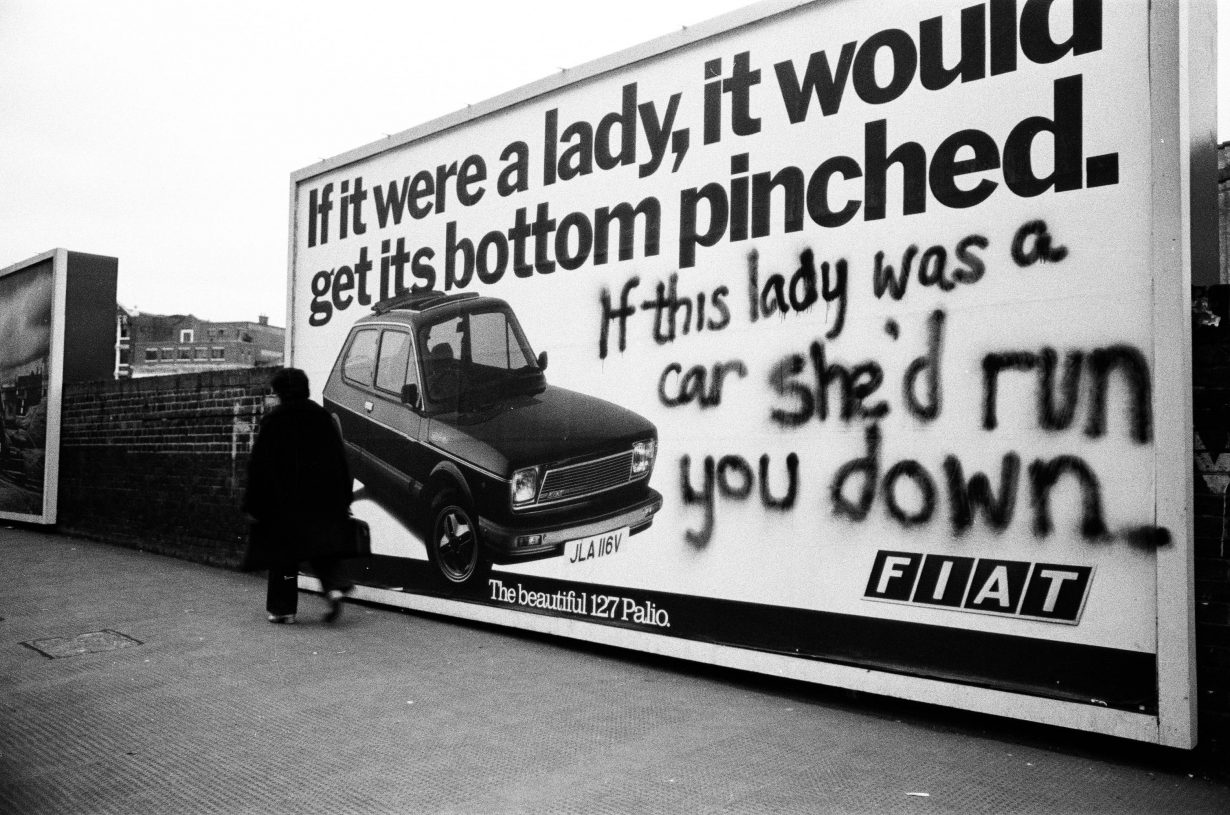

Messy and contradictory, foregrounding feminism in music and punk and conveying how women were actively organising, working intersectionally and creating alliances, while also experiencing profound isolation, the show presents a multitude of voices without silencing or forcing them into one narrative. The exhibition design, including plywood screens and multiple vitrines featuring zines, artworks and documentation, has a democratic feel whereby the space, shared by over 100 artists, feels balanced rather than directed to foreground art stars. The tone ranges from humourous and irreverent to passionate and critical. Jill Posener’s Fiat Ad, London (1979) – a photograph of a billboard reading ‘If it [this car] were a lady, it would get its bottom pinched’ with ‘If this lady was a car, she’d run you down’ spray-painted underneath – hangs opposite artworks with non-glamorous images of female bodies and their secretions. Alexis Hunter’s The Marxist Wife (still does the housework) (1978), a series of images in which a woman’s hand cleans a photo of Karl Marx, comments on unacknowledged domestic labour. There are multiple representations of sexuality, such as the self-portraits of Rosy Martin’s Transforming the suit – What does a lesbian look like, Part I (1987) and Poulomi Desai’s Nothing Between Denial and Acceptance (1965), showing the artist holding a knife to her breast or with her arms crossed. The indelible contribution of Black and Brown women to the feminist movement is amplified throughout. For instance, in the remade relief Good Housekeeping III (1985/2023) by Marlene Smith, which focuses on the story of Cherry Groce who was shot by the police, prompting the 1985 Brixton riots.

The exhibition holds the public and the communities represented with care, which is reflected in adjustments such as the hanging of artworks and making of vitrines at wheelchair height. The wall texts ground the works in social and political struggles, as well as biographical and art historical context including key dates of gender- and sex-related laws. This curatorial care contrasts with the historical neglect many of these artists have experienced. That several works were remade for the exhibition proves their earlier lack of institutional and commercial support.

The exhibition includes artworks by trans woman artist Erica Rutherford, however, by ending in 1990, the show avoids exploring trans feminism and propagates the pervasive lack of research on trans artists, who seem to have been excluded from the art communities of the time, despite their prominent contribution to feminist and gay/lesbian liberation movements, as Juliet Jacques acknowledges in her catalogue essay. Moreover, interracial alliance is evident in the ephemera from collective organising, but less so in the artworks themselves – with work by artists of colour largely confined to two rooms. Besides these shortcomings, Women in Revolt connects multiple forms of resistance, from environmental activism to the women’s strike, communicating feminism’s urgency across generations. Above all, it captures the collective nature of struggle, mutual support and the joy women experienced being together – in itself revolutionary in a world centred on men.

This was felt all the more in contrast with Re/Sisters: A Lens on Gender and Ecology at the Barbican, which we found to be feminist in name, but not in politics. The focus on lens-based art gives it a measured, clinical feel, producing a National Geographic-like approach to landscape that feels at odds with its ecofeminist emphasis, and even, dare we say, reproduces the colonial gaze. The intergenerational and global remit of Re/Sisters certainly brings to view some powerful works. We were moved by The Grindmill Songs Project of the People’s Archive of Rural India, a collection of folk songs handed down through generations of women while toiling at the grinding stone. It remains unclear how these songs about women’s lives and work relate to either ecology or the camera. A more explicit representation of the exhibition’s aims is melanie bonajo’s film Night Soil – Nocturnal Gardening (2016), which features four women’s interspecies relations to specific environments, from old-growth forests to the Navajo desert. Susan Schuppli’s film COLD RIGHTS (2022), arguing for the right of ice to remain cold, is an important reorientation of perspectives and politics in the exhibition, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s Touch Sanitation (1979–1980/2017), where the artist thanks and shakes hands with every refuse collector in New York City, is another feminist high.

Medium-specific, the exhibition does not address photography as a feminist or ecological tool. Instead, it groups artworks by loose topics (such as ‘Extracting Economies/Exploding Ecologies’) and displays under these banners artworks of complex colonial histories. For example, Salt Island (2022) by Mónica de Miranda comprises five photographs forming the image of a riverbank settled by a community of enslaved people. The foliage has been meticulously embroidered, but the significance of altering the image is not further explored. Instead, this image is adrift in a multitude of photographs of landscapes, its urgency is lost and its relationship to ecology is ambiguous.

In Ridykeulous’s Ridykes’ Cavern of Fine Inverted Wines and Deviant Videos, the emphasis on a single medium did not feel limiting, as it plays to video’s strength: its accessibility, playfulness and performative potential. Evident in the broad range of installations from large-scale projections like Charles Atlas’s evocative imagery of the late Leigh Bowery alongside portraits of ravishing drag queens in Turning Portraits + Guest (2020/23) to the scrappy and DIY in the carpeted Rush Stadium, a platform by Sam Roeck featuring multiple artists’ videos playing on individual monitors.

Cocurated by Ridykeulous (artists Nicole Eisenman and A.L. Steiner), joined here by Sam Roeck, the exhibition brings together 30 artists, bridging older pieces with work by younger and lesser-known artists, suggesting intergenerational support and cross-temporal kinship, inclusive of all genders. Given the prominence of Eisenman – who currently has a solo show at the Whitechapel Gallery in London – and Steiner, this show demonstrates how artists can use their visibility to wedge open the door for others.

The exhibition foregrounds issues of ecology, colonisation and climate crisis – in the context of gender and sexuality – and platforms marginalised or racialised artists and regions. For instance, A.K. Burns’s three-channel video What Is Perverse is Liquid (NS 0000) (2023), cuts between scenes in a limestone mine, an abandoned IBM office building and a swamp, and Oriana (2022) by Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, filmed largely in Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Maria, features feminist militants charting their way from the legacy of patriarchy.

Where Ridykes’ Cavern and Women in Revolt inspire, Re/Sisters disappoints. Feminist exhibitions provide a space for reflection at a moment of huge protest and public mobilisation, in response to #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, Just Stop Oil, the atrocities in Israel, Palestine and Ukraine, and the suppression of women’s freedom in countries including Iran, Saudi Arabia and the USA. As we imagine alternative futures, we turn to these exhibitions to ask how tactics developed by our feminist foremothers might help us tackle pressing issues, from the climate crisis and war to ongoing struggles around feminised labour, objectification, sexual violence, childcare and reproductive rights? What methods of organising and voicing can we take forward to secure feminist worlds?

2007 was known as the year of feminist art. That it has taken major UK art institutions so long to support feminist artists makes us wary about their long-term commitment. Truly supporting marginalised artists and practices requires systemic change. Contemporary art is notorious for coopting forms of resistance after the event, fetishising past or distant struggles as ‘archival’. Will these exhibitions add to the soft power allure of a ‘subversive Britain’, so evident in the ‘rebellious feminist’ T-shirts, mugs and notebooks filling Tate and the Barbican’s gift shops?

What is feminist about these exhibitions? The answer lies in their recognition of collective action, mutual support and the celebration of difference. At the same time, to be feminist, these institutions will have to undergo genuine transformation – not just display radical artworks, but practise the collective, intersectional and progressive values that these works advocate for.

This text was written collectively by Beth Bramich, Lina Dzuverovic, Sabrina Fuller, Taey Iohe, Mariana Lemos, Katrin Lock and Helena Reckitt. The Feminist Duration Reading Group was set up in 2015 to explore under-represented feminisms from outside the dominant Anglo-American canon. It has met across art galleries, community centres, parks and living rooms in London and elsewhere in the UK, as well as in Italy, Toronto and in a podcast commissioned by Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof and HFBK Hamburg. The FDRG is led by a working group of five and a support group of a further five. It is currently in residence at Goldsmiths CCA. www.feministduration.com