RE/SISTERS: A Lens on Gender and Ecology fails to offer a new lens on power, collective responsibility – or resistance

‘Where there is power, there is resistance’, wrote Michel Foucault in the first volume of The History of Sexuality (1976). Gathering work by 50 international women and non-binary artists, RE/SISTERS: A Lens on Gender and Ecology at the Barbican presents an attempt to map precisely such points of resistance immanent to power. Attesting to personal and collective acts of revolt, here rooted in and reflecting the diversity of ecofeminist thought and practices, the (roughly) 250 works in the exhibition challenge the colonial capitalist logic that sees the earth as a reserve to be exploited. Taken together, they also serve to connect oppressions along lines of gender, race and class – drawing on the structural insights of ecofeminism as delineated in foundational texts like Francoise d’Eaubonne’s Feminism or Death (1974) and Carolyn Merchant’s The Death of Nature (1980).

Two works on view privilege such links, or an approach that centres lived relationships with the environment. Susan Schuppli’s COLD RIGHTS (2022) pays close attention, through sound and image, to the changing material state of ice and the life it sustains. The voiceover references a provocation put forth by Inuk activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier (in a petition titled ‘Seeking Relief From Violations Resulting from Global Warming Caused By Acts and Omissions of the United States’, filed on behalf of herself and 62 Inuit people living in the Arctic regions of Canada and the USA) where she defends the ‘right [of ice] to be cold’. Dismissed by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2005, the claim for ‘cold rights’ and for a climactic sense of justice, Schuppli’s films shows, has never been more urgent.

Taloi Havini’s Habitat (2017) engages the sociopolitical history of Bougainville, an autonomous region within Papua New Guinea and Havini’s birthplace. The three-channel film follows Agata, an elderly Indigenous matriarch and landowner, as she travels from the tailings to the pit of the Panguna copper mine, the epicentre of the Bougainville Civil War in 1988-98, today recognised as one of the deadliest conflicts in Oceania since World War II. Through a combination of aerial footage – surveying an expanse of wetlands, abandoned infrastructure and barren tributaries of a water system marred by lingering pollutants – and views from the ground, Havini captures a devastated ecosystem shaped by colonial violence but where, somehow, an Indigenous local population survives. One of the aerial views in the film shows Agata engaged in informal small‑scale mining, a practice or form of labour understood to be ‘unproductive’. At a certain moment, while working through gravel in large framed sieve, Agata looks up; her gaze meets that of the camera, thus interrupting the aesthetics and logic to which we’ve become accustomed, of extraction as abstraction.

Made by women and foregrounding Indigenous perspectives and claims to the land, these two moving-image works challenge uncritical approaches to thinking through the intimate relationship(s), which RE/SISTERS thematises, of environment and gender. Against the mythical equation of women with nature, they speak to an affinity in and for the earth that is socially and historically constituted – an affinity or ‘a position of proximity’, to employ Kathryn Yusoff’s expression from her text for the exhibition’s catalogue, ‘that is the product of material and structural relations […] which configure the [epoch] “we” are now said to be in (the Anthropocene) – namely, the earth practices and subjective practices of colonialism.’ It is those practices which produce certain (gendered and racialised) bodies as earth-bound, and others as citizens of the world (understood here in its forgetting of, but also as parasitic on, the earth).

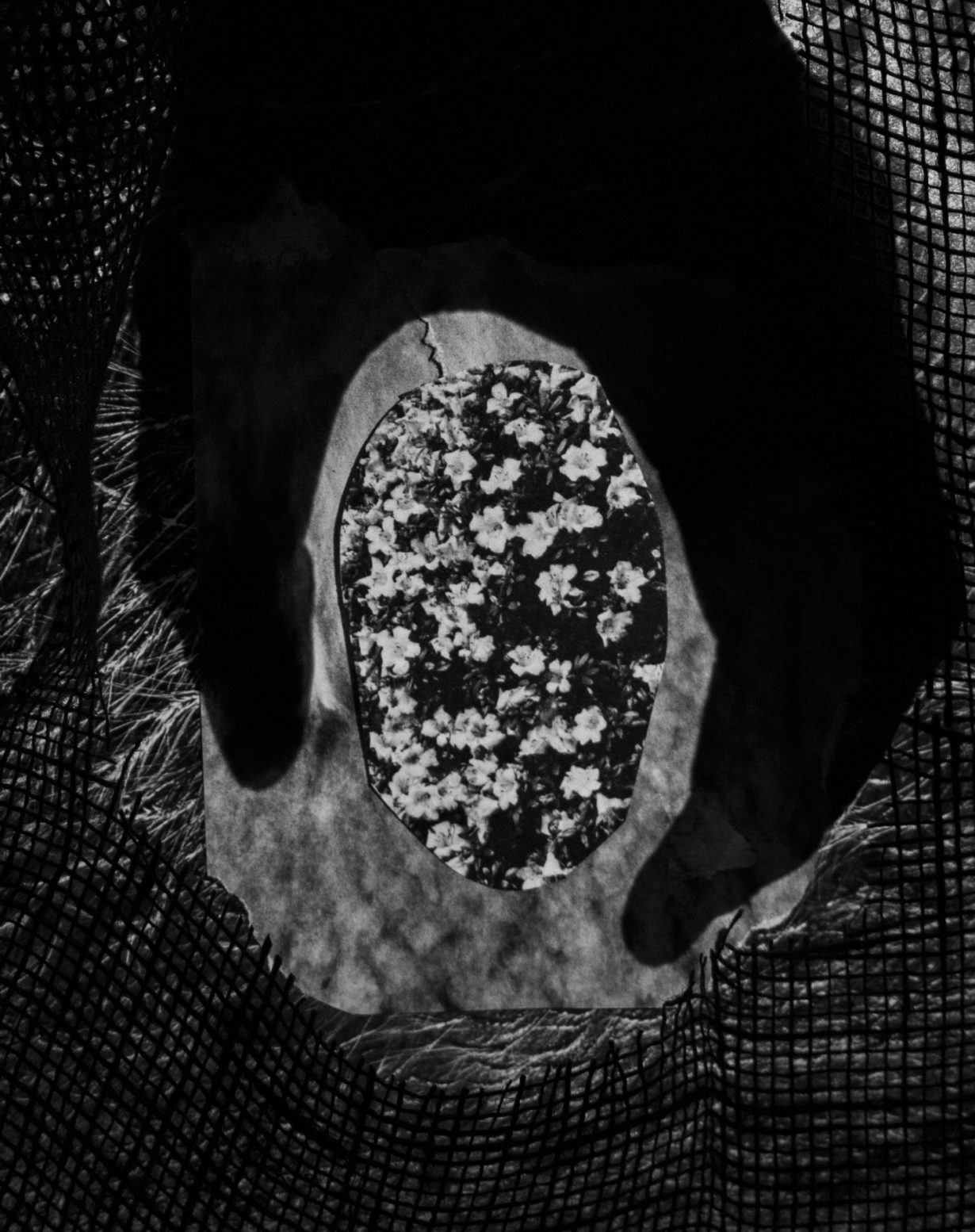

Dionne Lee, in her collage work, directly engages such histories of the racialisation of bodies and the foreclosure of the commons. Offering manifold, delicate images of the American landscape, Lee poetically thinks through legacies such as the unfulfilled promise of ‘forty acres and a mule’ to freed slaves in 1865, listening for their echoes in the present. Trespass is the most beautiful word (2017) shows an abstracted hand reaching for a pocket of land through a barrier net. The work invites viewers to think about the close relationship between race and spatial differentiation – to ask what kinds of bodies are permitted or denied access to the earth under the global regime of ‘group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death’ that is racial capitalism (in the words of American scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore). Through her title, Lee, of course, simultaneously affirms that, ultimately, we are all trespassers, all visitors on this planet.

By bringing together provocations such as those by Schuppli, Havini and Lee, RE/SISTERS states its intent is to ‘encourage a more reciprocal, grateful, and joyful relationship with our animate Earth’. While an encounter with individual works certainly helps move us in this direction, the exhibition as a whole disappoints. It gathers works in groupings that feel both predictable and a little perfunctory (here, the ‘politics of extraction’; there, the bodies of Laura Aguilar, Ana Mendieta, Francesca Woodman and other artists reclaiming earth…) and remains faithful to traditional white cube display strategies that privilege representation over interaction. This does little to trouble the forces that structure the relationship between the artwork, the viewer and the site, meaning that RE/SISTERS does not succeed in involving audiences or in making us feel the urgency of it all.

The more general question, in other words, is of how to do justice to these works of and about environmental and gender justice. Given that ecological devastation and systemic injustice are two of the biggest challenges facing societies today, isn’t it time that art institutions and curators follow artists and activists in enacting (rather than ‘inspiring’) the change we want? Such a shift would require an adventurous reinvention of modes of participation, as well as asking what the museum itself can be beyond its known configurations. Hope can be and has become reactionary. Embodying social alternatives might mean having to offer audiences not only new and diverse stories, but perhaps the institution’s infrastructures themselves – holding up a space where people could think, feel, talk and experiment together. It might also mean troubling the modernist (normative) imperative of hope and its forward tempo to make room for an attentiveness that challenges us to stay with the trouble instead, as Donna J. Haraway would have it, and to (re)think agency and accountability in a now composed of more-than-human interdependencies.

Leaving the exhibition and its faint call for collective responsibility, I am reminded of a similar, more direct call by Fred Moten in an interview from 2013: ‘The coalition emerges out of your recognition that it’s fucked up for you, in the same way that we’ve already recognized that it’s fucked up for us. I don’t need your help. I just need you to recognize that this shit is killing you, too, however much more softly, you stupid motherfucker, you know?’ I, like Moten, long for a muddy solidarity grounded in recognition of our often involuntary complicity and shared vulnerability.

Lilly Markaki is a cultural theorist moving between London and Athens.