Artists in India are increasingly faced with a dilemma as state intervention in galleries and museums becomes ever-more brazen

Once every month, since he came to power in 2014, the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi delivers a monologue on radio called Mann ki Baat (‘thoughts of the mind’). On air he shares his thoughts on everything from Indian cultural and social values to sports and women’s health, children’s education, cleanliness and the environment. There are chatty details about his frequent trips overseas, new governmental programmes (always with catchy Hindi names) and a regular spotlight on a citizen or an initiative in line with the developmental vision he and his government have for the country. These have included a pencil manufacturer in the conflict-torn state of Jammu & Kashmir, an environmental activist in the Himalayas, and a woman entrepreneur from Manipur – all chosen for the strategic value they offer to his personal brand as a benevolent, beloved leader who cares for his people.

Mann ki Baat has become an increasingly important political tool for the Prime Minister as his image has taken a severe beating in recent months: significant electoral losses for his party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP); horrific violence in different states; allegations of corruption and collusion with corporate empires; protests by Olympic athletes over alleged sexual harassment by a powerful member of the BJP; and severe inflation and rising unemployment, among innumerable other issues. Modi has met these problems with near total silence. Instead, he projects an image of India where, contrary to reality, everything is mostly fine. Mann ki Baat, which he has claimed is a matter of faith and a spiritual journey for him and not just a radio programme, is a huge part of his demagogical posturing in a country severely polarised in the years since his right-wing party came to power.

This April, the programme reached a milestone 100 episodes, which the government unsurprisingly sought to commemorate with a slew of events. These included a national convention attended by film stars, business people and celebrities; the release of a commemorative stamp, a ₹100-coin; and an extensive social media campaign. Attendance to the public events where the episode would be streamed was reportedly made mandatory in several educational institutions and for government employees; there were reports of the suspension of students who refused to participate in the adulation of the country’s leader.

It was amid this media frenzy that Jana Shakti: A Collective Power, curated by art historian and curator Alka Pande, opened at the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) in New Delhi. The artists exhibiting were Atul Dodiya; Vibha Galhotra; Riyas Komu; Ashim Purkayastha; G R Iranna; the artist duo Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra, who make work under the name Thukral & Tagra; Manjunath Kamath; and Jagannath Panda. Kiran Nadar, the philanthropist, collector and founder of Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA), participated in an advisory role for the exhibition. While none of the works in the NGMA exhibition are new commissions for the show, the text accompanying each work was tweaked by the curatorial team to make it seem as though it was responding to a theme from episodes of Modi’s radio show. Topics ranged from water conservation to yoga, female empowerment to COVID-19 awareness. No matter what compelled the artists to participate in the exhibition (if there were any such pressures at all), their association can be read as acceptance of, if not support for, the state’s programmes.

While traditional art forms – folk or otherwise, religious and secular – are popular in India and widely seen and used, contemporary art, transacted mostly in urban centres and often in English, remains the domain of the few. Save for some public art, works that are shown mainly in galleries, sold in art fairs or collected in museums have limited reach – and therefore a narrower influence over India’s vast population. This is perhaps why contemporary artists have largely been left alone until now. The Hindi film industry, however, wields immense cultural influence and would be hard pressed to operate smoothly without the tolerance, if not the approval, of the government. Even prior to Modi’s election, mainstream Hindi films were hardly known for tackling progressive ideas head-on: since 2014, directors have clambered over themselves to make propagandist films like The Kashmir Files (2022) and The Kerala Story (2023), or chest-thumping nationalist films like Uri: The Surgical Strike (2019). Rewards have come in the form of tax exemptions, awards and other such state-sanctioned perks.

Could the artists who participated in Jana Shakti, and others in the artworld who might follow in their footsteps, be gunning for something similar? Comments posted by various critics and artists on public forums and social media, including the artist Pushpamala N in the Indian Cultural Forum, suggest that at least some of these artists may now be in the running for high-value government commissions or have a place at the Indian Pavilion at the upcoming Venice Biennale. Or they might be taking the long view, choosing to align themselves safely with the ruling conservative party as India slips further away from its long-cherished democratic, syncretic values. The safe spaces for dissent and freedom of speech are diminishing while crimes against women and minority communities are on the rise, set against the collapse of impartial mainstream media and an almost palpable atmosphere of hate and intolerance in society.

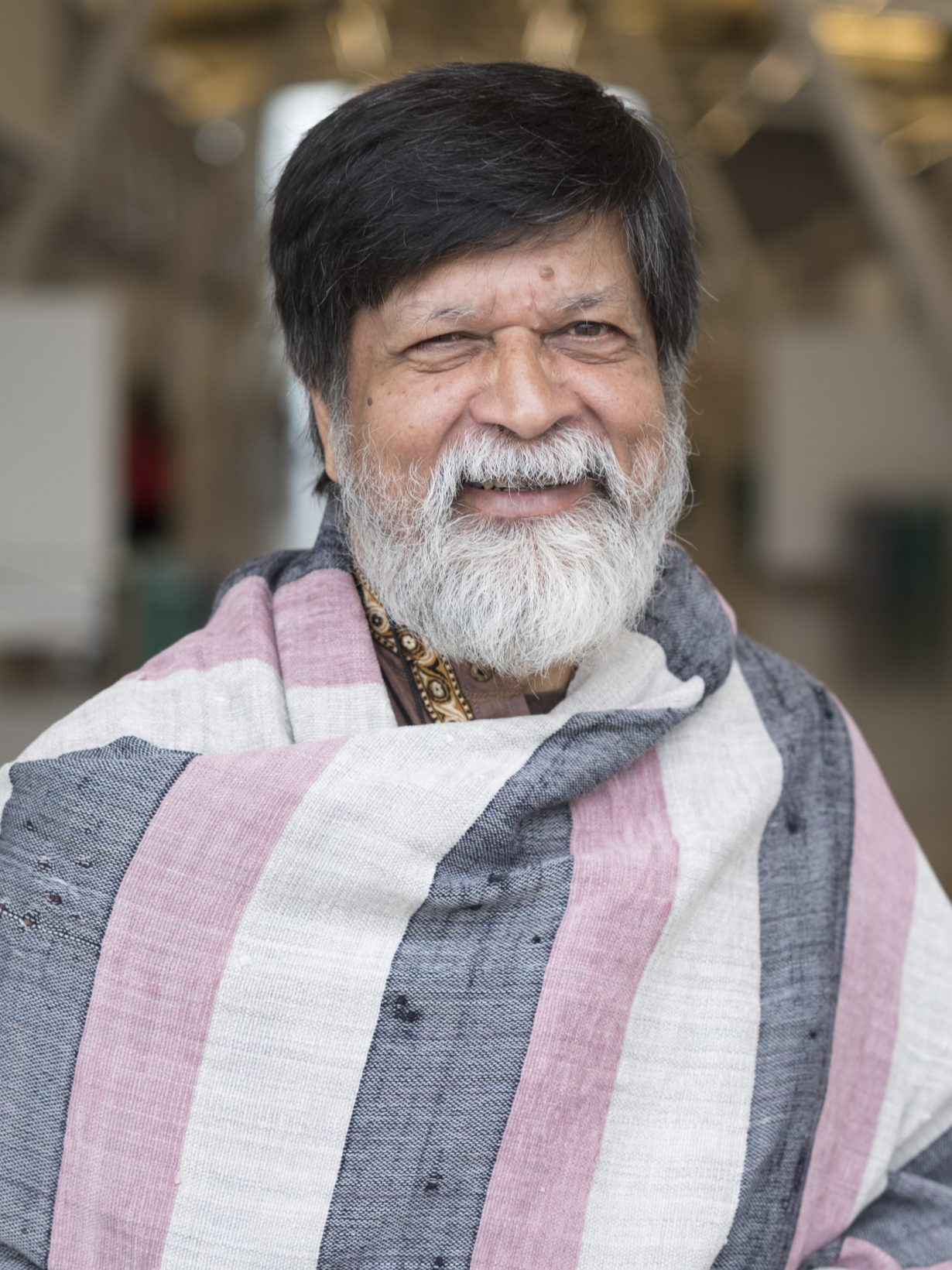

Earlier this July, Dr Sandip K Luis, manager of curatorial research and publications at KNMA, was fired from his position for a comment he wrote on his personal Facebook profile criticising both the NGMA show and KNMA founder Nadar’s part in the project. A statement signed by hundreds of artists, liberals and intellectuals expressing solidarity with Luis and demanding his reinstatement is currently doing the rounds. The Bangladeshi photographer and activist Shahidul Alam, who was to have a retrospective at KNMA in July, announced that he was withdrawing from the show in protest. This was, he explained, due to Nadar’s endorsement of ‘art events which are part of the propaganda machinery of the current Indian regime, and the censure of people who make legitimate critiques of such associations’.

In an unfavourable economy, the decision to compromise on politics often comes down to money. It is through this lens that the collaboration of supposedly liberal artists with a conservative regime can perhaps best be understood. Yet it must be noted that all the participants in the NGMA exhibition are well-established artists with decades-long careers, their work collected by museums around the world and selling at high prices. Seen in this light, one wonders if money from state patronage could be the only motivation, or if this represents a more fundamental ideological shift.

Independent funding for contemporary art in India is severely limited, and the amounts often too small for artists to really live and make work with – unless they find other funding sources, residencies, biennales or arts festivals both within India and abroad. Though non-government-funded institutions might operate with relative freedom, if one were to trace their donors and patrons, the money would eventually would lead to the same small pool of corporate donors, business families and private philanthropists – many of whom are known to be cosy with the current government and, by extension, supportive of its divisive policies.

When forced to work under such shifting political allegiances, where does one place personal ethics? Should artists, like the ones seen to support Modi’s troubling ideology, be held responsible? Is it right to expect our artists to be activists too? Perhaps it is for these artists themselves to consider their part; and for history, if this chapter is allowed to be written at all, to judge such actions.

Deepa Bhasthi is a writer based in Kodagu