From ancient Dionysian rites to Bongripper, Harry Sword’s Monolithic Undertow celebrates the pleasures of slow, sustained sound

From Byzantine chant to avant-metal, why have we always been so attracted to the pull of slow, sustained sound? Harry Sword’s Monolithic Undertow searches for our relationship to drone music: an epic playlist that begins in the womb, then criss-crosses an exhaustive thread across the lo-fi Vedantic cassettes of Alice Coltrane, the ‘true British blues’ of Black Sabbath, infrasonic weaponry and the gritty doom-clouds of The Velvet Underground. What could it all mean?

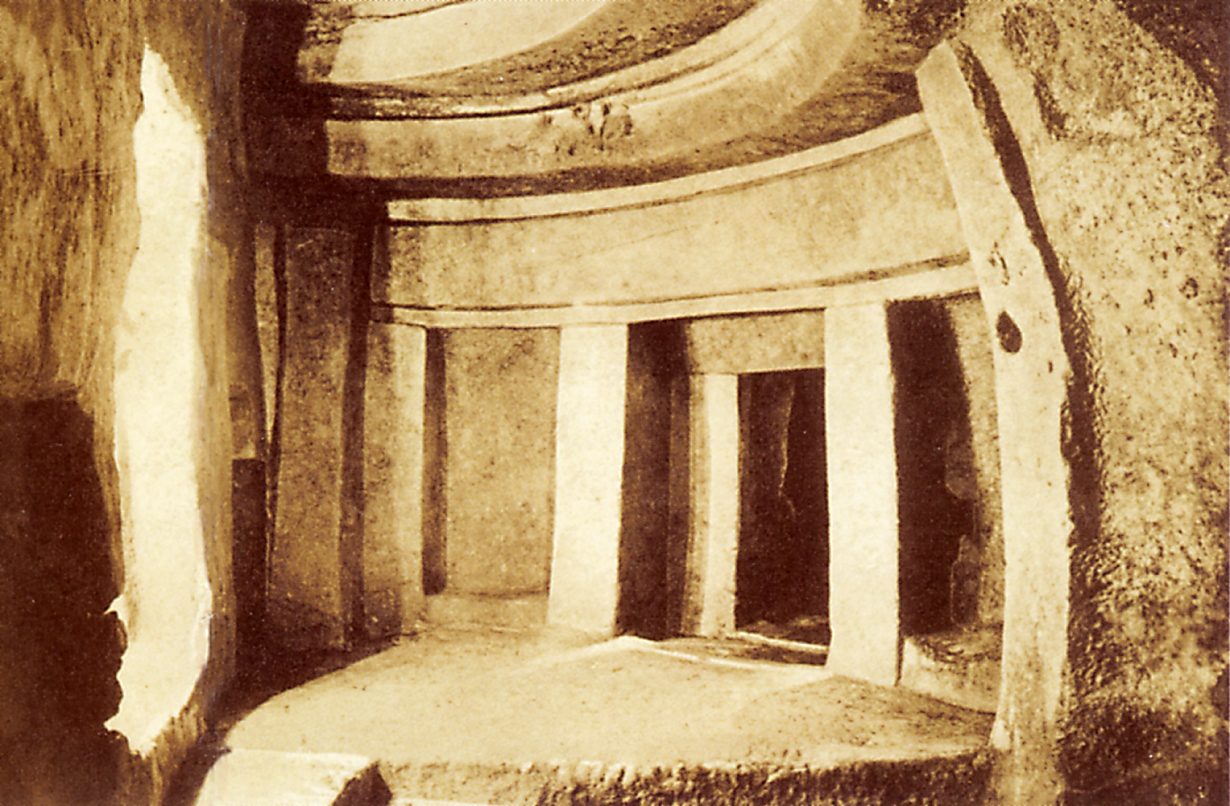

‘In the form of ringing reverberation of psalms, the deep bass of the organ,’ Sword writes, the drone ‘maximises the intention of belief’, evoking astral worlds beyond. Imagine the shrieks of Ancient Greece’s aulos pipes, with their suggestions of derangement, creating a ceaseless drone that accompanied the orgiastic activities of Dionysian rites. Or the sonic frequencies of a Neolithic subterranean necropolis discovered on the island of Malta, brought to life by archaeo-acoustics. Descending into the resonant bowels of its Oracle Room, Sword envisions the kind of sound rituals that might have played out millennia ago.

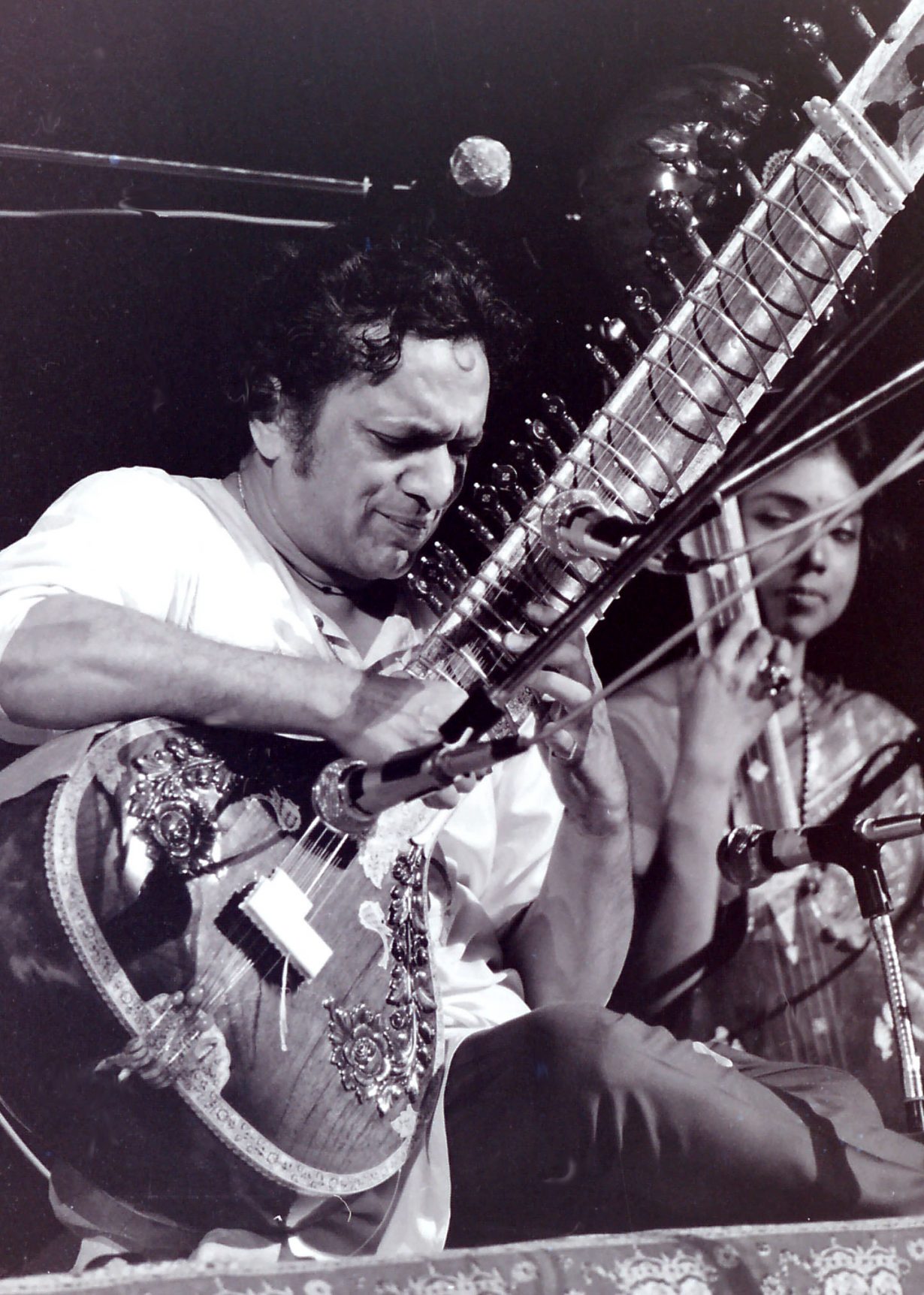

Soon you begin hearing the drone everywhere. In his account of how the 1960s Western rock aristocracy rushed to incorporate the

sitar drone in their music, Sword drifts into a description of mind-warping psychedelics. And indeed, what is acid but its own drone, Sword argues, describing the sonic consequences of consuming LSD – the ways in which it begins to shift the brain’s workings: ‘Acid disrupts the frontal cortex that affects our perception of sound… Time becomes blurred, sounds echoing and bleeding into one another.’

It’s a pity that Monolithic Undertow’s quest for sonic nirvana doesn’t encompass the ways in which the drone has seeped through online music-making. (Look up the anonymous YouTuber who stretched out a Justin Bieber hit – U Smile 800% Slower, 2010 – turning candied pop into a grandiose ambient-drone block- buster.) But Sword is too engrossed in the in-real-life shock of what this stuff does to you: the wall of sound that hits when Sunn O))) blasts a guitar chord through distortion pedals, or mainlining hydroponic weed while stumbling through a wailing Bongripper set. It’s the ultimate folk music, Sword concludes, ‘a potent audio tool of personal liberation’.

Harry Sword, Monolithic Undertow: In Search of Sonic Oblivion, White Rabbit Books, £20 (hardcover)