‘You’re beginning to see what will be the final consequences of colonialism, the destruction of indigenous traditions, as patrons want something Westernised’

The Wallace Collection in London is hosting Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company, curated by the award-winning historian, writer and broadcaster (and cofounder of the annual Jaipur Literature Festival) William Dalrymple. The exhibition, which roughly spans the years 1770 to 1840, is billed as the first in Britain dedicated to the Indian artists who were commissioned by British patrons associated with the East India Company, artists whose work (much of which was destined for export to Europe) has been generally grouped, by art historians and curators, under the umbrella term ‘Company Painting’ rather than credited to individuals. Moreover, the exhibition attempts to argue that these individuals deserve a place in the history of Indian art rather than being confined to a footnote in the history of colonialism. ArtReview Asia spoke to Dalrymple, whose most recent book, Anarchy, a history of the Indian subcontinent during the collapse of the Mughal imperial system (1739–1803), was published in 2019.

ArtReview Asia Broadly speaking, it seems that you could characterise this exhibition as being about, on the one hand, switching the emphasis from patron to artist when it comes to discussions of ‘Company Painting’ and, on the other, talking about this period of history in terms of collaboration rather than exploitation.

William Dalrymple Correct. The East India Company was very different in so many ways from the Raj. The two are often elided as if they’re one thing – the colonial period – but they’re very different. The East India Company is far more extractive, far more about loot and plunder and profit, but it’s also a period of collaboration: the East India Company was working with Indian bankers, as there were very few Brits in India – never more than 2,000 at any one time in Bengal, and the head office for 100 years in the history of the company only had 35 British employees. The money to pay for the mercenary regiments of sepoys, which grew to 200,000, twice the size of the British Army by 1799, largely came from Bengalis who invested in company bonds and from loans from Bengali bankers such as the Marwari Jagat Seths [the most powerful bankers in India during the first part of the eighteenth century – to the extent that they were known as ‘the bankers of the world’].

One in three Brits was married to an Indian woman during this period. These kind of contacts – sexual, artistic, intellectual, philosophical – were in stark contrast with the Raj proper, which tried to dress up imperialism in terms of a civilisational mission: building railways and hospitals and universities, and pretending that it was there primarily for the sake of India, when it was totally separate and racist. The Civil Lines, where the whites would live [known at the time as White Towns], were quite different from where the Indians would live. There was the famous sign ‘No dogs or Indians on the mall’, whites-only clubs, all that sort of thing. What people forget is that the East India Company was around for 250 years while the Raj was only around for 90, just 1858 to 1947. So this show is about expressing the difference of this earlier extractive, but collaborative, period.

ARA Do you see it as sort of reconfiguring of Indian art history or British art history, or somewhere between the two?

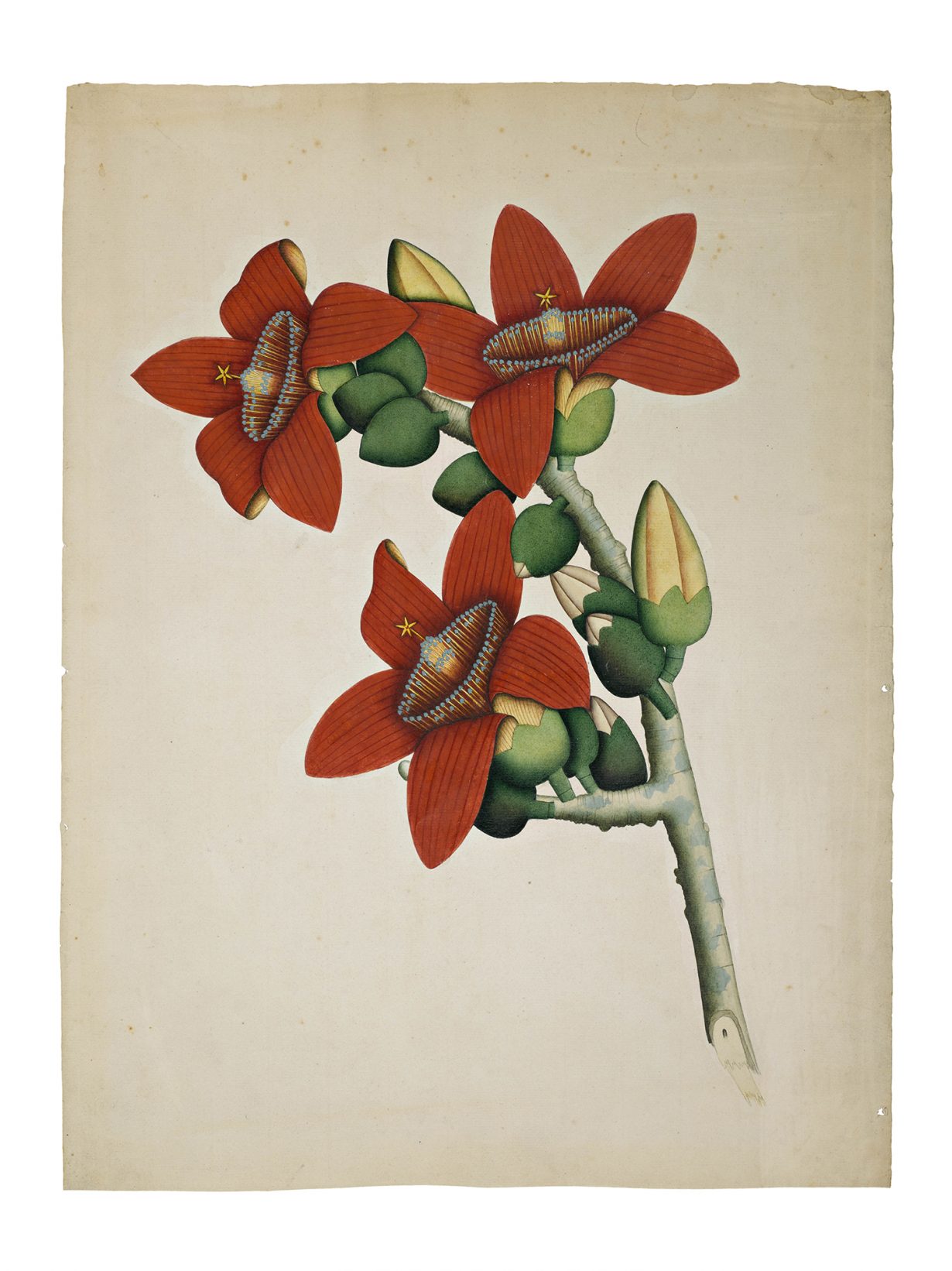

WD It’s a period that has been ignored in both, because it doesn’t fit into either. It’s not British artists like Tilly Kettle or Johann Zoffany coming out of India and painting pictures that would sit easily in, say, the Freer Gallery of Art [part of the Smithsonian Institution dedicated to Asian art in Washington, DC] or a Tate show on eighteenth-century art; but nor is it recognised anywhere as part of Indian art, because it was done so clearly for East India Company patronage, in quite a lot of cases with Western ornithological or botanical models being given to these artists. And yet these pictures showed work of astonishing quality.

ARA Do you think there’s a sense in which neither historians of British art history nor historians of Indian art history want to see this period this way, that it’s not convenient in terms of what happens after it?

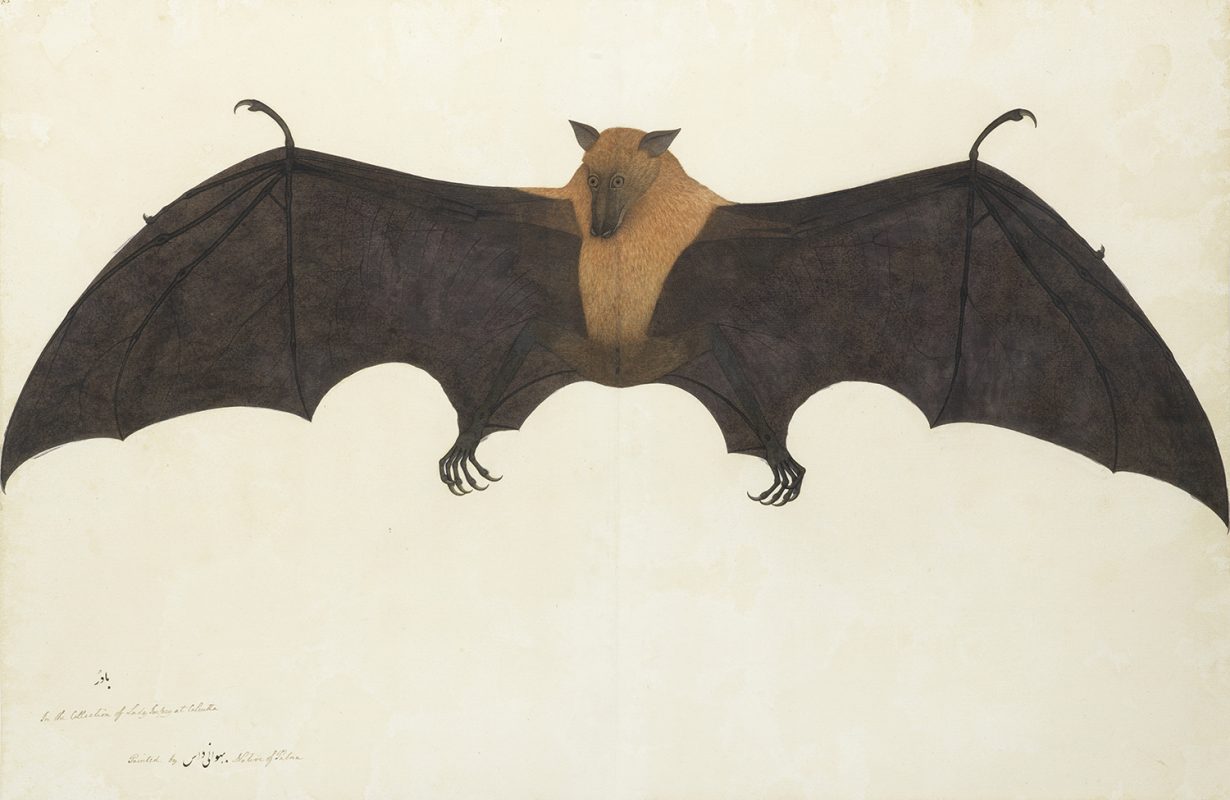

WD I don’t think it’s a deliberate ploy. I think this work is still pretty obscure. When [the curator and taxonomist] Henry Noltie went looking for botanical drawings in the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew [in London], he found several hundred if not a thousand Claude Martin pictures sitting in the Kew archives, not only unpublished but not accessioned. That is, in a sense, the biggest discovery of the show: the sheer body of work sitting in Kew that was never noticed before.

ARA But isn’t that part of a colonial programme: to record the flora and fauna as part of an essay on ownership?

WD Let’s not romanticise this. The East India Company was an executive multinational business that was there to make money and it didn’t see botanic gardens primarily for the edification of botanists and lovers of nature, Indian or British. It was so that it could find things to sell. Whether it was ginger, coffee, cocoa or opium. That’s why they were involved in this project. But you also have the fact that they got a bunch of enthusiastic botanists, who were probably kept awake at night with the thrill of all this new stuff, out to do this. You have these competing motives.

Calcutta, 1780. Courtesy: Gift of Elizabeth and Willard Clark, © Minneapolis Institute of Art home

Very few of these pictures, if any, come out of the patronage of the East India Company with the capital EIC: it’s individuals doing the commissioning. The Fraser Album [a collection of paintings documenting various aspects of Mughal life, made between 1815 and 1819, commissioned by a British Indian civil servant from notable Mughal painters] is produced by William Fraser partly because his brother James wanted it, but also, I think, partly out of his own curiosity. He’s recording the names of villagers he’s working with and taxing: rather like a headmaster having images of all his pupils today. On the other hand, the images in Agra are really, I think, produced by Indian artists as tourist postcards. They realised that they could sell these things. Ditto the work of artists like Yellapah of Vellore and Shaikh Muhammad Amir of Karraya [active during the 1830s and 40s], who seem literally to be knocking on people’s doors and offering to paint their horses, dogs and servants. So they can make an album to send home or keep as souvenirs, back in the days before photography and postcards.

ARA Do you think that this is the beginning of a kind of modernity in Indian art, the beginning of a break with tradition?

WD I think you’ve got to be a little bit careful about that because people are just recording what they’re seeing.

ARA But the way they’re recording it is changing slightly; it is, in a way, more scientific.

WD No question. Someone like Claude Martin, who was very much aware of being alive during the triumph of reason is studying scientific journals and so on, sitting in Lucknow. Three years after the Montgolfier brothers put their balloon up in the middle of Paris, he’s got one going up in Lucknow, based entirely on the descriptions in scientific journals that he’s having sent out from Paris. In the same way, while he’s employing Mughal artists in the tradition of Ustad Mansur [active 1590–1624] to paint these animals with incredible hyperrealism, he’s also training them to do cross-sections, which never would have occurred to a Mughal patron to want or need.

ARA Do you see it as the moment of change within Indian art, in those terms?

WD It’s several things. At the beginning of the story, it’s a development in the Mughal tradition, for instance, in that you’ve got Mughal artists being asked to do something slightly different. I think in some of the earlier stuff from Lucknow you have the same miniature landscapes, these sorts of Lilliputian landscapes that you see in the background of Mughal work in this period. Then gradually it becomes more Europeanised, so you get white backgrounds and cross-sections. Then the artist Sita Ram [commissioned by Lord Hastings to illustrate a diary of his journey from Calcutta to the Punjab in 1814–15] is in a sense copying William Hodges and the artists of the [English] picturesque movement. And you’re beginning to see what will be the final consequences of colonialism, the destruction of indigenous Indian traditions, as patrons want something Westernised and European-looking rather than something Indian and traditional.

ARA Do you think that having an Indian artist record these Anglo visions is a way of naturalising the Westernisation of Indian art?

WD I think it’s more accidental than that. I think that they were very fine artists hanging around Calcutta who probably didn’t cost a great deal to employ. We think it was probably Hastings’s wife who somehow got hold of Sita Ram because Hastings’s diary doesn’t mention him at any point, yet he’s clearly going around in the same party. There isn’t much Sita Ram in the show because it’s a different aesthetic. We’ve chosen one particular look here: everything is on a white background, everything is hyperrealistic and incredibly detailed. You could have done a very different show with extremely colourful Thanjavur painting [a classical South Indian style, which originated in the Maratha Court, 1676–1855], which is also Company School, or work coming out of Putna by an artist called Sewak Ram [c. 1770–1830], who, in the end, we didn’t show. This is by no means encyclopaedic.

ARA The word ‘beauty’ comes up a lot in your catalogue essay.

WD Ultimately that’s why we’re having the show: these things are just stunningly good. They’re very, very beautiful and they’ve never been seen before in England. No one knows about them. It’s not often in art history that you get something of this quality that has never been shown before. There was one show in New York in 1978 [Room for Wonder: Indian Court Painting during the British Period, 1760–1880, organised by the American Federation of Arts] and there was a little one in Bombay last winter. But really this is kind of virgin territory.

ARA Also I guess it comes at a time when decolonisation is a big thing in relation to cultural artefacts.

WD Yes, and again this work occupies an awkward space in that debate. It’s not the really complicated stuff like the Benin Bronzes looted by European armies, about which a very good case can be made for their recovery. This doesn’t quite fit: it was always owned by Europeans and was never in Indian hands. It was patronage for artists who had, in many cases, fallen on hard times because the courts were being rolled up by the Company. And those that weren’t, such as the Mughals, were definitely finding things hard financially.

ARA In that context, this is not a story that a lot of institutions would be focusing on right now, in their rush to admit guilt for everything.

WD Well, I think that is a story that no one has focused on. On the Indian side, arguably the greatest-ever show of traditional Indian precolonial painting was put up by the art historian B. N. Goswamy with his The Way of the Master: The Great Artists of India, 1100–1900 at the Museum Rietberg in Zürich in 2011, which then travelled to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in a slightly smaller form and with the title Wonder of the Age. That show was encyclopaedic about the major artists of India and very much went against the old colonial method of cataloguing artists according to place: the Kangra School or Delhi School or Jaipur School and so on. Instead, The Way of the Master was catalogued by the names of these forgotten individuals. It brought to light Nainsukh and the other great Indian artists whose names had been, until recently, forgotten. But, rather uncharacteristically, the show just had ‘Company Work’ at the end. There was one Ghulam Ali Khan from The Fraser Album and maybe one work from The Impey Album [commissioned by Mary Impey, beginning in 1770 and featuring 300 paintings by artists including Shaikh Zain al-Din, Bhawani Das and Ram Das]. This catalogue is an attempt to extend Goswami’s project into this period, which, to my eyes, is when some of the most gorgeous stuff is being produced. Also, stuff which gets the highest price in the saleroom.

ARA Would you like to show this in India as well?

WD I’d be delighted to show it in India. There’s huge interest. People are intrigued that these works predate photography, they are among the first pictures to record costume types, traditional forms of labour, forms of art and forms of craft. They show ways of living and ways of dressing which had been forgotten. The catalogue follows the Goswami model, in a sense, in that we’re trying to establish biographies, names and identities for these artists, as the title suggests: Forgotten Masters.

ARA I wonder if you can compare this late-eighteenth-century, early-nineteenth-century period, this in-between phase of art being Indian yet international, to what’s happening with contemporary art in India?

WD One of the tragedies of colonial history in India is the degree to which it finished so many currents of Indian art, culture and civilisation. Not completely, because there was a lot of India that remained uncolonised: one quarter of India was still ruled by princely states. Cultural patronage continued, so you’d get ballads and poets and court artists and so on, and while some of those courts ended up copying Western modes of architecture and preferred photography to miniature painting, for example, many didn’t. So you have traditions which survive to this day, coming out of those courts and those ateliers. The Indian contemporary artist is looking very much over its shoulder at Damien Hirst and whoever the contemporary masters are that provide inspiration. There are some who will give it an Indian idiom like Subodh Gupta with his pots. Or Bharti Kher with her bindis. But there’s no sense in which Bharti or Subodh’s work is actually flowing out of traditional Indian painting. There’s a radical break and that break is colonialism.

Which is different, incidentally, to what’s happened in Pakistan, where the Lahore School of Art is growing traditional painting. Suddenly you can draw a real contrast there between the more contemporary-feeling work being done in India with the more traditionally based work by artists ranging from Shahzia Sikander to all the other alumni of the Lahore Art School.

ARA Why do you think that is?

WD I’m not sure. I’m intrigued. I think that the teaching at Lahore Art School happened to rely on a couple of amazing teachers during the 1950s and 60s who valued the traditional styles and the traditional forms of Mughal and Sikh art, and these traditions are still living. I get the impression that in Delhi, which is a more profoundly colonised place, there was just a complete break and that Sita Ram was the beginning of the end, seeing the way forward as painting in the Western style, not the traditional style.

Everything that followed in the next hundred years under all these colonial art schools only confirmed that cultural break. By the time that Valentine Prinsep is touring India in the 1880s he was already saying that he could find no one in Delhi producing good traditional local art. He said that the quality of the work that he’d seen from before the 1850s was so fine, but that today they were only making copies of them for tourists. The traditions had died. The reason was colonialism, the massacres of 1857 and the end of that whole world.

To my mind, the very worst thing that colonialism did was killing off the culture of this country. I think you can draw a very strong distinction between what John Lockwood Kipling [1837–1911, an English art teacher and museum curator who spent most of his career in British India] was encouraging his pupils to do in the 1880s, and what William Fraser was encouraging his artists to do. Fraser valued them for their skills – that’s why he was employing them; he wasn’t trying to get them to relearn how to paint a leaf or how to paint a house. He wanted them because he valued what they were doing. I think everyone who’s worked on this exhibition sees this – with the possible exception of Sita Ram – as Indian art, not colonial art.

Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company is on show at The Wallace Collection, London, through 13 September