Why do we sentimentalise Denes’s most famous artwork, recently revived among feminist and ecological discourse, and where has this led us?

As my landlord ushered me out of the Southeast London flat in which I had lived for the last half-decade, he mused that it was so much nicer in rural Dorset, the southwest England county where I was now about to live. This begged the question of why he had decided to move me out and himself back into the flat, having himself previously been ensconced in so much West Country niceness. Nitpicking, however, would have been futile in the face of English law.

The countryside, it is now my job to believe and explain to others, is beautiful, wholesome and clean. It gave us hills and potatoes; it gave us the villages we keep saying it takes to do things. The city, I was expected to conclude by the end of the week, was a hot, dirty bucket of asbestos – the rude epicentre of environmental decay.

Off I drove then in an aged car, which I quickly discovered was trailing a slick of petrol from its butt. But no matter, I was off to live in glorious smug, evicted idyll. If my landlord wanted even a sliver of those green and pleasant vibes in London, he would now have to fight it out with the local council. People, after all, had been fighting that fight for almost as long as I had lived in the area – shaking their fists at plans to build council flats on nearby patches of earth, embellishing the latter with titles such as ‘Peckham Green’. It was not that these protesters didn’t care about urban poverty or its housing crises, just that they’d been called to the ultimate confrontation – the war, as I believe they saw it, against ecocide itself.

I wonder if it is sentiments like these that, of late, have inspired such a revival of interest in the early ecological confrontations of artist Agnes Denes, the woman who in 1982 planted a little under a hectare of wheat on a slab of land in the Battery Park Landfill, Lower Manhattan. After 200 truckloads of soil had been spread and furrowed by hand, planted with seeds and tended over a period of months, the site flourished as an uncanny, faux-bucolic foreground to the World Trade Center, skyscrapers seemingly sprouting – if you looked at them from the ‘park’ – from a field of wavy gold. Once the crop was ripe and some appropriately disorienting photographs had captured it for good, the artist oversaw the harvesting of more than 450kg of grain. The piece – the artist’s best known – was titled: Wheatfield – A Confrontation.

In the years since this artwork first confronted what Denes named ‘mismanagement, waste, world hunger and ecological concerns’, it has often been reduced by commentators to a pastoral corrective to the evils of urban technocracy. In 2019, when Denes had a largescale retrospective at The Shed in New York, a reviewer at The New York Times spoke of ‘breeze-swept natural bounty’ rubbing up against the architecture of metropolitan greed. In 2022, marking 40 years since the original planting, The Guardian ran a feature in which columnist Katy Hessel described the work as a ‘rural idyll’ in the infamous concrete jungle. Pointing to a photograph of the artist tending to her crop, Hessel evoked an ideal of crusty femininity – stripy shirt, high-waisted jeans – to be contrasted with the ‘stocky’ centres of patriarchal commerce hovering behind. She lamented that it would now be impossible to pull a stunt like this in most cities around the world, where plopping vegetation in urban centres is supposedly at odds with the city’s capitalist ambitions.

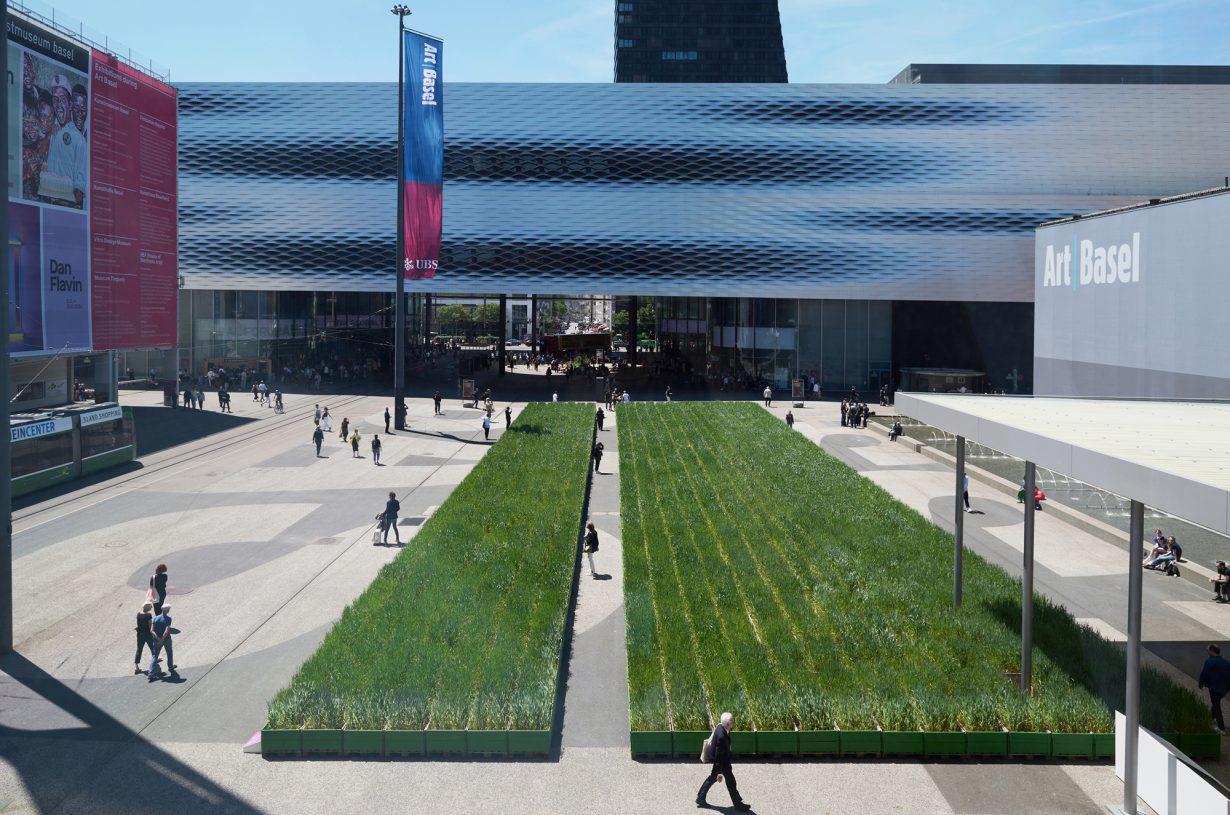

This is curious, since Wheatfield – A Confrontation was reprised in London’s Dalston in 2009, as well as in Milan in 2015 and last year in the middle of Art Basel – the so-called nexus of the art market. There is nothing uncanny, unfamiliar or indeed confronting today in these kinds of soil-on-concrete studies. Honoring Wheatfield – A Confrontation (2024), installed on Basel’s Messeplatz, covered 1,000sqm of concrete-lined plaza with hundreds of palettes of soil. Filled with seeds and green shoots, these moveable units of plant, designed to nod to an ‘iconic’ art piece, were of a piece with any number of the kind of urban ‘regenerative’ ventures that are now a hallmark of the contemporary capitalist cityscape.

Take, for instance, New York’s High Line, just a couple of miles up from where Denes’s Wheatfield once stood. Also constructed on a disused bit of land – in this case a section of elevated railway – this urban park is one of the most visited symbols in the world of what is now commonly described as ‘landscape urbanism’, a movement towards inserting ecologically robust planes of land to the urban environment, ideally boosting the aesthetic and economic value of that land in the process. The High Line’s success is measurable not only by its impact on human and environmental health and wellbeing, but also by visitor numbers, retail revenue and real-estate prices.

Who does it serve to conceptualise ‘greenness’ in such literal terms, to measure ecology in plants? While the High Line may delight tourists and educate children both local and not, it has also contributed to the replacement of regular housing with luxury condos, sweeping low- and middle-income residents from its zone of postindustrial pleasure. This kind of stage-managed wilderness – a model for similar projects in cities the world over – may appeal to the green sensibility, but as urban social theorists Natalie Gulsrud and Henriette Steiner have pointed out, it rests on an ‘ecology’ that excludes from its calculus those kinds of people and nature deemed unhelpful to the aim of accumulation. Not even the countryside itself, with its readymade greens and warming community spirit, is immune to gentrification, favourite child of ‘eco’ developers and the multiple-property-owning class.

If Denes’s Wheatfield is in fact meaningful (her simply stated ambition for the project), we cannot sensibly seek this meaning in its rural aesthetic alone. The work, after all, was not just wheat, or wheat in an urban landscape. It was wheat on a $4.5bn piece of real estate. It was manufactured use where there had only been exchange; it was a tangible, edible product distributed to 28 cities, its seeds carried off and replanted in various parts of the globe.

If the work’s visual impact rode on dissonance, this was merely a call to attention; no more was it to be taken literally than the artist’s decision, in 1998, to flood the manicured gardens of the American Academy in Rome with a herd of sheep. The point of Sheep in the Image of Man was not to idolise sheep, which as the artist wrote ‘plung[e] headlong in this direction or that, without plan or perspective’, but rather to provoke reflection on the resonance sparked by such a weird and jarring encounter. In the case of Wheatfield, the point was not the feminine idyll set against a backdrop of manspreading metropolis, but rather the needs-based, redistributive impulse thrown into the midst of speculative gluttony – a gluttony of which Wall Street and its buildings were merely legible symbols. Wheatfield’s vision of ecology was more than one of greenness pasted on greed; it was one in which the welfare of the planet was tuned to that of its most dispossessed humans.

If Wheatfield were, in fact, an urban regenerative project and not, instead, a temporary work of art, we would do well to be less impressed by its theatrics of rural charm. Prime urban real estate, after all, does not want to be filled with wheat; it wants to be filled with libraries, schools and social housing.

Agnes Denes’s sculpture The Living Pyramid (2015/25) is on view as part of Desert x 2025, Coachella Valley, 8 March – 11 May, where it is installed at Sunnylands Center & Gardens, Rancho Mirage, California

Amber Husain is a writer currently based in Bridport, England

From the March 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.