The Japanese artist on nature’s inspirations and taking on a plant’s perspective

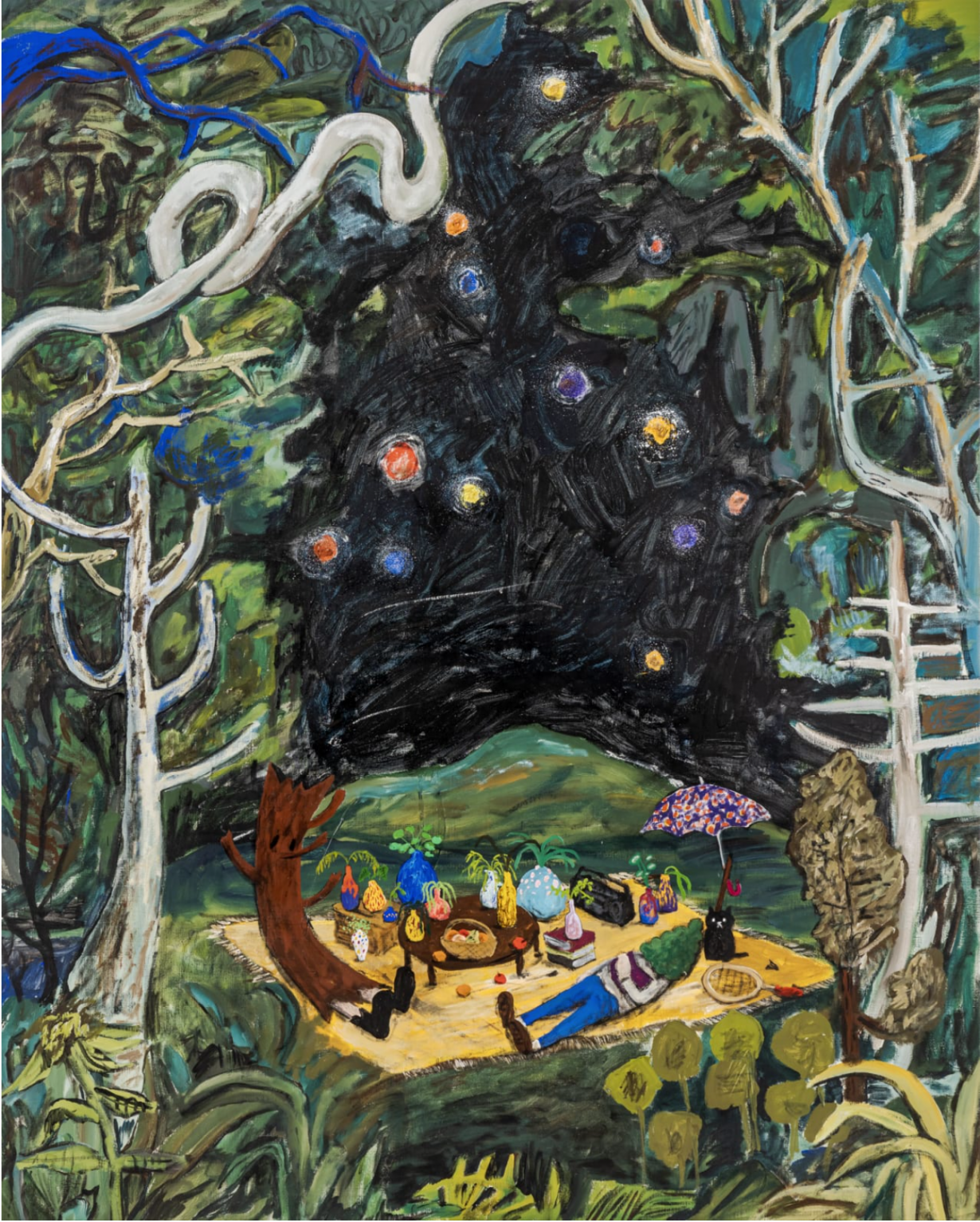

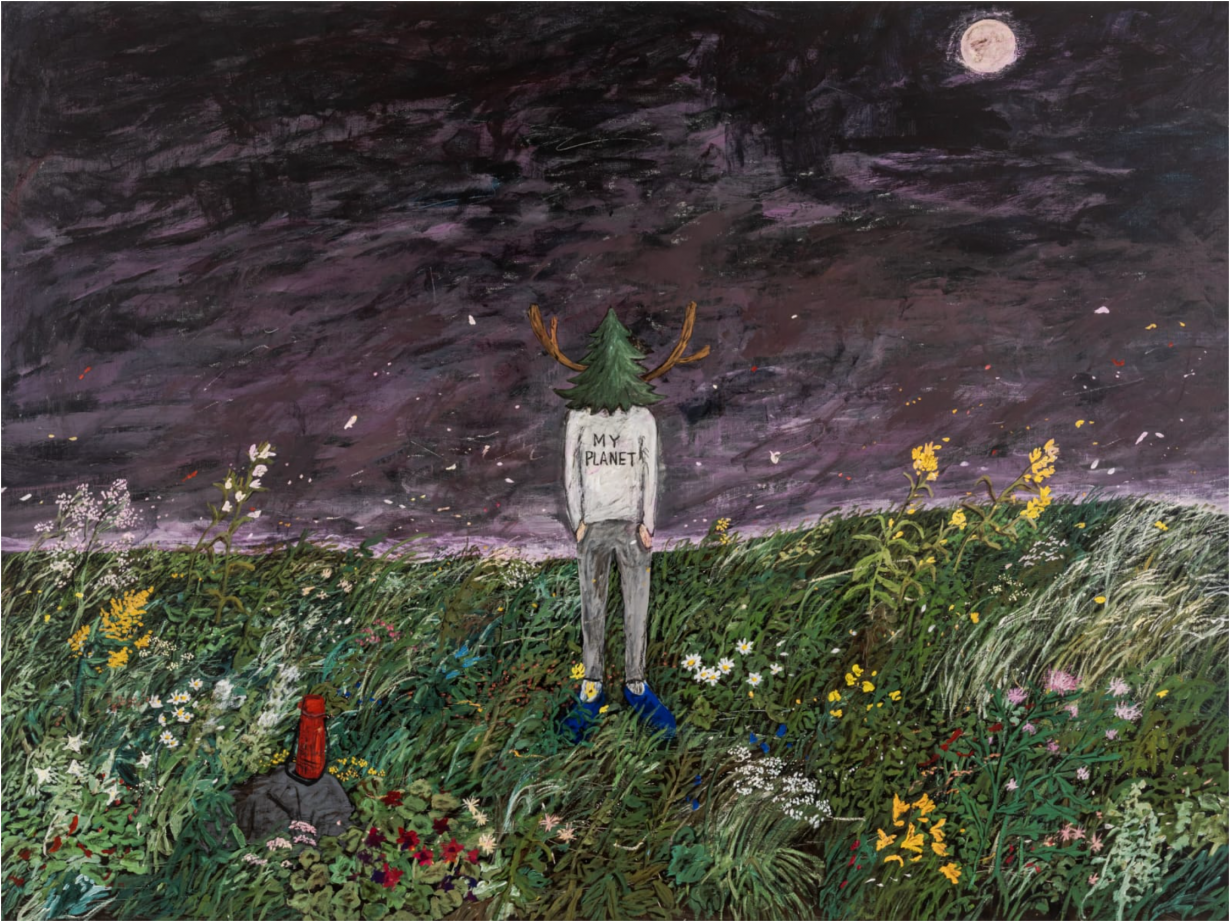

Born and based in Japan but trained in London, Yuichi Hirako produces artworks in a range of media, from painting and sculpture, to installation, sound works and performance. Many of his recent works (which featured this autumn in an exhibition at Gallery Baton in Seoul) focus on the relationship between humans and nature, between ideas of the wild and the cultivated, the cute and the sinister, while riffing off a suite of art-historical and cultural references from both the West and the East. Many of the works from his recent show, titled Mount Mariana, feature a seemingly mythological character dubbed the ‘Tree Man’, who has the body of a human, and a fir tree for a head that sprouts deer antlers from its sides. As his work goes on show at Gallery Baton’s stand at Frieze London, ArtReview Asia caught up with the hugely prolific artist to discuss his working practice and philosophy.

ARA What inspired you to become an artist?

YH I have enjoyed drawing and making things since I was a child. I especially liked drawing Manga – I used to make enlarged copies of my favourite scenes and draw copies of them on tracing paper. As for three-dimensional modelling, I used to make large buildings out of cardboard and cellophane tape. I was not very good at communicating with others, so I often collected insects or fished by myself. Perhaps I was immersed in my art to maintain my identity.

ARA In what way does that work?

YH I felt I was alone because my parents and my sister couldn’t really understand what I was feeling at the time and so I felt I had to choose something of my own. I tried playing in a band, cycling, but creating things really helped me. And it still helps me now. I enjoy making art, it’s my way of taking control of things.

ARA Is the process of making different from the process of showing?

YH I think I find something when I show my work in public – new connections with people. It’s a kind of language for me. When I talk with someone one-to-one I find I can’t really talk about myself, but I can when I show my work. I’m always using plants or nature in my artworks; I think it’s a common language – people understand nature, it makes it easy to draw people in and then they can discover the different meanings that are hidden inside the works. In a way they challenge common understandings – for example, at a basic level, we might learn from our parents that flowers are beautiful, but that’s not totally true. In a way I’m playing. When Japanese people, for example, look at my work they always say it’s cute or it’s pop, it’s easy to see. But I’m hiding a lot of things behind that. Of course, if you want to see cute, it’s cute. I don’t think it’s cute. It’s about the more serious and dangerous things that are happening to the planet. For me, great art always seeks to change people’s minds or the way in which they view the world around them.

ARA Last month you showed a series of new paintings and sculptures at Gallery Baton in Seoul. What were your influences for the works in this show? The press release mentions Arcimboldo and Plato, and the ‘Tree Man’ character – which appears as part human, part plant and perhaps part deer. But in the works on show there seem to be other references, to Shintoism (in which deer often play the role of messengers) for example.

YH My influences include religions such as Shintoism and Christianity, animist ideas, industrial history, and secular modern ideas about plants and nature. The Tree Man in my work is a portrait of myself, and also a portrait of anyone who has any kind of relationship with plants or nature. Some people find environmental issues in them, some people think of Shinto ideas, and, as I said before, some people simply think they are cute.

194 × 162 cm. Courtesy the artist and Gallery Baton, Seoul

ARA You were born and are based in Japan, but trained as an artist in London. Do you think that Western and Asian traditions have both influenced your work, and what aspects of each are you drawn to? Indeed, do you think there remains a contrast between these traditions, is this kind of discussion even relevant? After all the distinction is not necessarily particularly apparent in your work.

YH I think Japanese and Asian traditions are more focused on sensory expression in art. I think the situation has changed a bit in modern times, though. On the other hand, the West is more rational. I was well-trained in my classes at university to build a strong conceptual process of creation. So it’s like a mix of the two senses in me. I find myself constantly struggling with rational ideas, and those that go against the consensus.

ARA Are you looking for a kind of rationalism in the work?

YH I like to mix between the rational and the non-rational. When I was a student, I was trying to create clear things, but it was tough. My original mind was not like that. More Asian, more Japanese. I read a lot about ecology, about intelligence in plants. There are a lot of people researching that. Just as much as I think there are lot of people researching what nature is or what plants are. I’m looking for answers in the work and to think about those questions alongside other people, like my viewers.

ARA Were you ever tempted to make a garden instead of a painting?

YH Gardening already has its answers. They want to control plants in their area, enjoy it in their area. In a city or urban situation in particular. People think that, for example, the tree in the street and the tree in the forest are the same thing, but they are not.

ARA The title of the exhibition at Baton, Mount Mariana, suggested an inversion of sorts – land for sea and a mountain for the Mariana Trench (the world’s deepest oceanic trench, located in the Pacific Ocean). Why reference a seascape and represent a mountainscape? Does this reflect a wish on your part to use your art to reverse current attitudes and perspectives? And how does art (as opposed to protest/activism/etc) achieve this?

YH When I was discussing the show with the gallery, the director suggested that I use a title that would evoke the imaginary place where the characters in my work might live. At first I thought this was a little too obvious, but then I thought it would be an interesting way to convey the world of my work in a superficial, or pop, way. As to the second part of the question, I believe that art can create a situation in which the viewer’s senses are shaken, in other words, a situation in which a problem that needs to be solved is contained while presenting a seemingly acceptable subject.

(Right) Yggdrasill 04, 2021, acrylic paint, wood, metal, FRP, 222 x 90 x 65 cm

Both images courtesy the artist and Gallery Baton, Seoul.

ARA You constructed that show, as with previous ones, with characters that we can follow (if we choose to) from one work to the next, in much the same way as a storyboard from a movie might do, allowing characters to develop, in a way, beyond mere individual representations. Perhaps you can explain your working practice (and the influences of other media on your work)? Does the work evolve from a narrative or a message (as say a painting like Lost in Thought 64 or a sculpture like YGGDRASILL 05, both 2021, might suggest) or is it firstly visual?

YH My current work process is divided into two main parts: research and production. I use a lot of literature and the internet for research. When I’m working intensively or at the stage of creating a new style, I tend to rely on music. It’s like letting out my accumulated thoughts without much emotional organisation. I don’t care whether the message of the visual information comes first.

ARA What is the significance of the black cat that appears in several of the works?

YH I often use cats, dogs, and birds in my works, as they are able to go back and forth between the natural and human worlds, and in a sense, they are symbols of danger.

ARA We also follow characters from one medium to another – from painting to sculpture, for example. What changes about them when they move from one medium to the next (the sculptures after all retain a painterly feel, and mirror the objects represented in your paintings)? In the current show it would seem as if, say, the subject of a painting like Gift 15 (2021), also becomes a viewer or observer of the work in the form of the sculptures placed alongside it.

YH Yes, that’s right. In the process of creating works across different media, the boundaries sometimes become blurred. The point of view is only human, but it may be important to think about what we should be aiming for when we put ourselves in the position of plants and nature. Both, our point of view and the other side’s point of view, are correct.

ARA A work like Gift 15 (2021) is a portrait of the Tree Man standing in front of a wall of portraits of plants, on the one hand it appears to suggest a symbiotic connection between humans and non-humans, and on the other it represents a relation between nature and culture, which in Western art-historical traditions are often represented as opposites. In this painting the Tree Man appears as a form of construction while the painted flowers appear natural. Do you think that the kind of symbiosis you suggest in the form of Tree Man is also present between nature and the many things (the products of culture or science) man creates?

YH In fact, the plants depicted in the background of this picture refer to commonly available flowers. They are sold in flower shops. On the other hand, the head of the Tree Man refers to wildflowers and endangered plants. Both of these situations are symbiotic. As long as we are alive, we must continue to make some kind of choice.

ARA Are you pessimistic about the future of the planet?

YH I am not pessimistic at all. In an extreme example, there may be a future where humans continue to destroy the environment and nature will die out. That’s one choice. I will continue to research the current situation and history and incorporate it into my work. That is the only thing I can do.