Collaborative networks remain vital for sustaining the country’s creative talent

On a typically slow Saturday on the cusp of the hottest month of October, dry winds sweep foot traffic from Lusaka’s city centre into a yellow-pillared art gallery. Curious passers-by rub shoulders with young creatives and street vendors at the entrance of Maingaila Muvundika’s solo exhibition, Mwaiseni Mukwai, taking place at Everyday Lusaka.

What began as a cultural initiative on Instagram in 2018 to challenge monolithic representations of Zambia defined by wildlife, poverty and the Western gaze evolved into the physical Everyday Lusaka gallery and project space in 2024 through the vision of Indian-Zambian curator and gallerist Sana Ginwalla. The curatorial focus is mainly photography: the gallery previously exhibited the black and white street photographs and self-portraits of Alick Phiri, one of the few remaining professionally trained Black Zambian photographers who practised from the 1960s to 1990s in Lusaka and whose images travelled with the space to 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London last year.

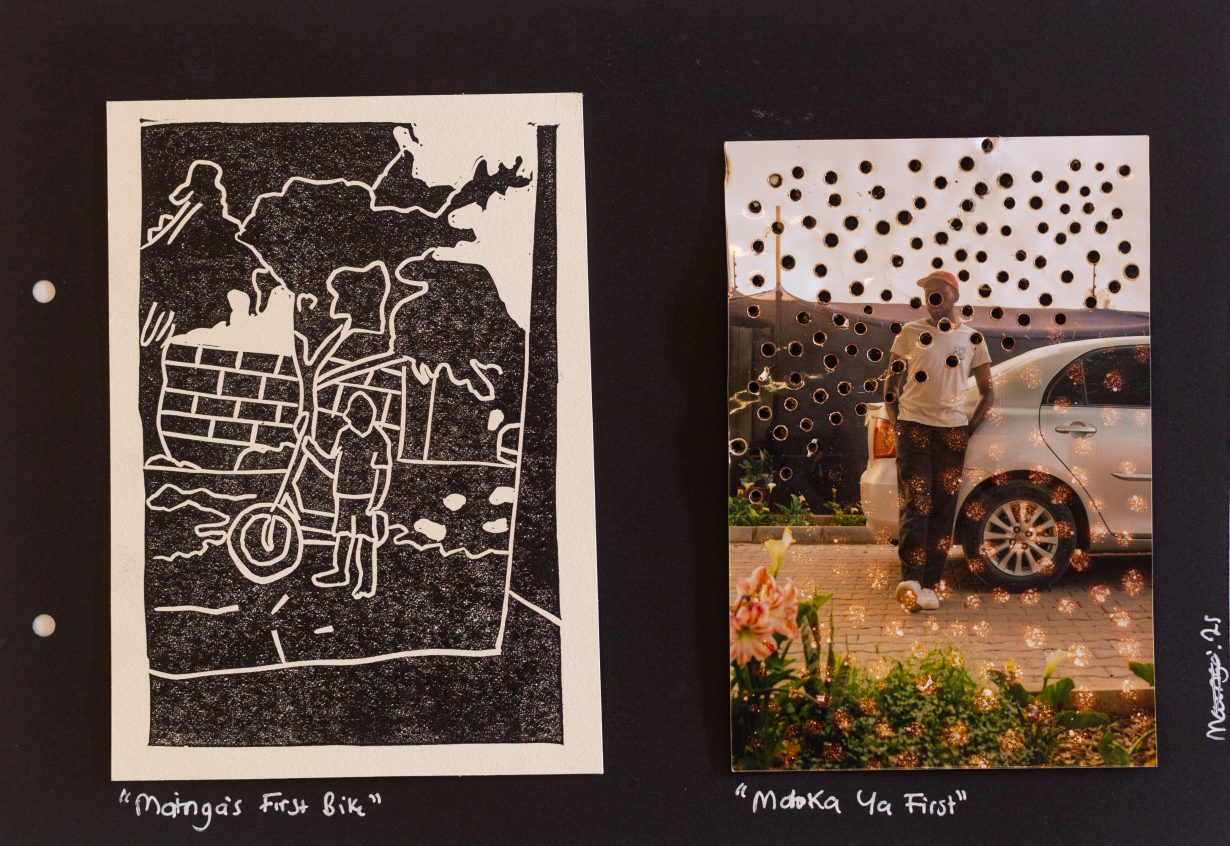

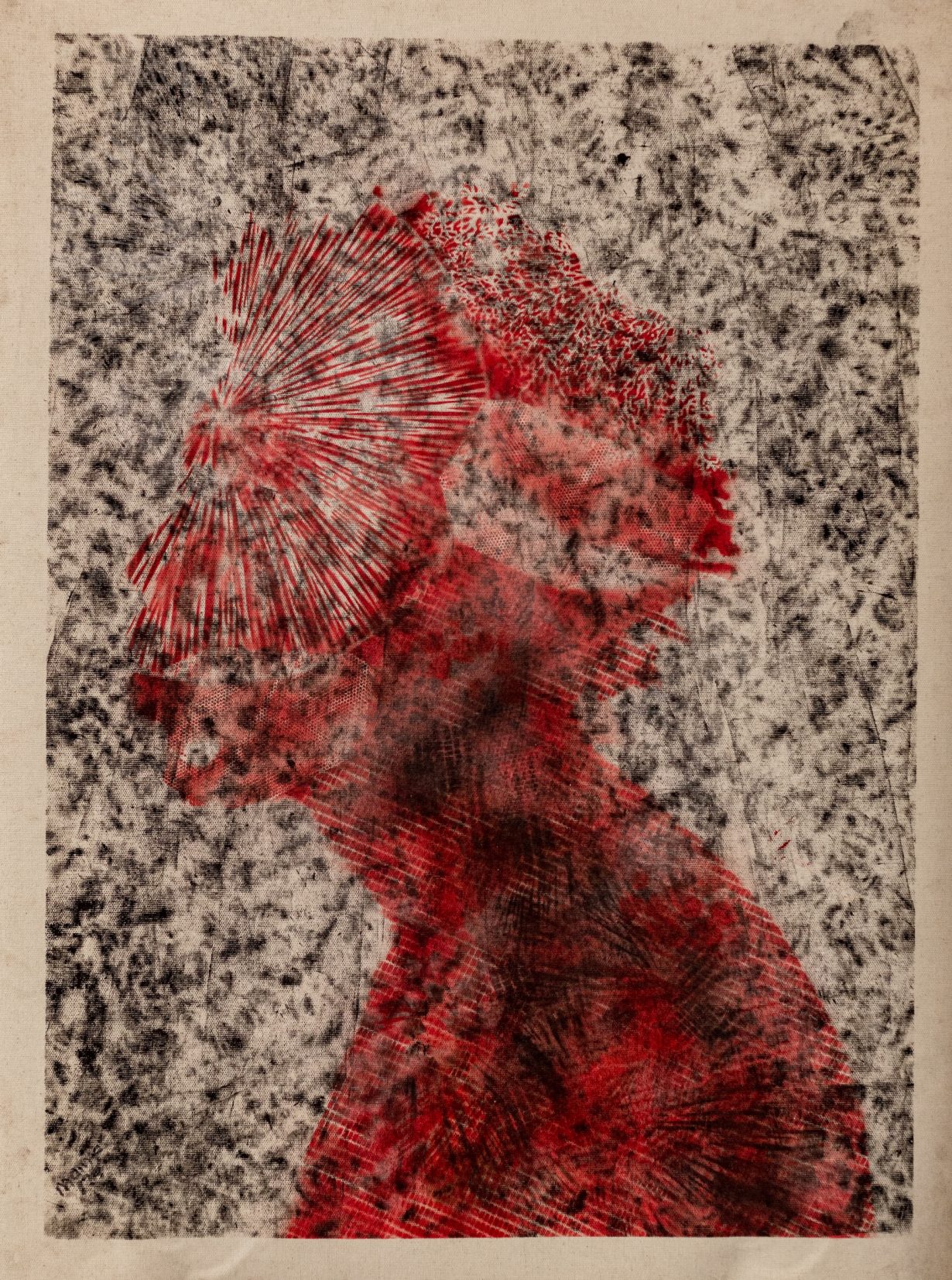

Now, Everyday Lusaka remains committed to the street photography images that initially populated the Instagram page, recently hosting a ‘photo walk’ around the gallery’s surrounding streets led by British-Zambian photographer Sein. Previous exhibitions include long-time creative ally of Ginwalla, David ‘Daut’ Makala, a self-taught artist whose practice incorporates drawing, printing, found materials and concrete sculpture. There’s a clear web: for example, Makala is also the founder of Studio225, a collaborative self-funded studio in the Chilenje area of Lusaka with a printing press that the artist built himself, where Everyday’s current exhibiting artist Muvundika explored printmaking techniques to produce Mwaiseni Mukwai, the name understood as a welcoming greeting in the Bemba language. In the exhibition, the lens-based artist revisits personal, institutional and embodied archives through a contemporary visual language of linocut printmaking and photographic self-portraits, inviting contemplation on how one’s image is constructed and displayed to the public.

Making use of his own family photo albums, material relating to Zambia held in the Cambridge University Royal Commonwealth Society collection and the Centre of African Studies archive, as well as his own photography and the Zambia Belonging counter-archive (an online project founded by Ginwalla collecting private portraits and photos from across the country), Muvundika constructs a repertoire of visual signs that carry a haunting resonance across a series of multimedia collages. He complicates these archival images of familiar scenes – a funeral procession, the artist on a school trip, gestures of relatives in an embrace – by obscuring the finer facial details through the linocut process. This makes certain details opaque, using oil-based ink block print and spray paint that imbue a sense of faded memories. Layered onto the images are punctures and signs of decay, drawing attention to the processes of remembering though archive while confronting our presumptions of photographic imagery as truth.

Through Everyday, Ginwalla set out to create a space for art that is accessible to the everyday Zambian while carrying on the Zambian tradition of artists building initiatives to serve their own needs. When the Zambia National Visual Arts Council (VAC) was founded in 1987 by artist and lecturer Martin Abasi Phiri, along with fellow artists Agness Yombwe and William Miko, it was born out of the exclusion of artists voices from national cultural policy. Miko describes alternative art spaces as intermediaries that bridge “the gap that exists between the formal growth, institutional policy, and the practical aspects of the creative sector.” As he puts it, “the Zambian art scene has started locomoting and these alternative spaces are the tentacles making the octopus move forward.”

Meanwhile, Zambian practitioners Anawana Haloba and Victor Mutelekesha went on to establish independent art centres in Livingstone and Lusaka after studying fine art in Norway at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts in the 2000s. It’s not uncommon for emerging artists and aspiring curators to trickle out of Zambia to advance their practice: beyond Evelyn Hone College of Applied Arts in Lusaka, where both Haloba and Mutelekesha began their arts education, further studies are often explored elsewhere due to a lack of art institutions in the country.

“When you grew up in Livingstone, you went to church and the National Museum every weekend,” says Haloba, explaining why the city was a natural place to build an art centre. Regarded as Zambia’s tourism capital, and home to the country’s oldest museum as well as the Mosi-oa-Tunya (known worldwide as Victoria Falls), the city became the site of the Livingstone Office for Contemporary Art (LoCA), founded in 2014 by Haloba and Mutelekesha with a network of artists and curators from across the African diaspora including South African curator and artist Gabi Ngcobo and Zambian artist Milumbe Haimbe.

LoCA emerged from ongoing discussions about the connections between art and political histories and the evident gaps in Zambia’s presence within institutional archives, which Haloba and Mutelekesha wanted to fill in a locally-rooted way. Since its inception, LoCA has operated collaboratively with surrounding cultural institutions, including the National Gallery which was built the same year.

The family-run Wayi Wayi Studio, directed by artists Agness and Lawrence Yombwe, is also part of the mutually supportive artistic network in Livingstone, facilitating workshops and hosting events. LoCA runs a series of incubators that share ideas of non-hierarchical and intergenerational exchange, one such being Sonic Solidarities, which was held in August 2025 in the buildup to the Mosi Oa Tunya Perennial, an ambitious large-scale international exhibition that will take place in September 2026 across Livingstone, Zambia and Victoria Falls organised by LoCA. The gathering invited thinkers and artists from across Southern Africa to reflect on the region’s contemporary art landscape and Livingstone’s historical situating as a corridor for exchange in precolonial and independence eras. Running concurrent was the exhibition How to Cook a Resistance, a group exhibition by LoCA curator Lineo Segoete at the LoCA Gallery and the National Musuem, featuring artists including Chansa Chishimba, Sello Majara, Em’kal Eyongakpa Mbi and David Chirwa (Bar’Uchi) who explored sound and the role it plays in mitigating space.

In the constellation of the Zambian art ecosystem, Haloba and Mutelekesha are linked by the Art Academy Without Walls, a cooperative project in Lusaka managed by VAC and administered by the National Art Academy in Oslo between 1996 and 2006. The project was spearheaded by Norwegian Professor Michael O’Donnell and Zambian Artist Germain Ngoma, operating as a transnational formal art education program at institutions across Europe for Zambian artists. VAC co-founder Martin Abasi Phiri garnered funding from the diplomatic community, foreign development agencies and the Norwegian Government, and in turn, Art Academy Without Walls hatched a new wave of Zambian artistry.

While LoCA’s programming includes studio-based critical inquiry through its Studio Program, its sibling space Lusaka Contemporary Art Centre (LuCAC) offers a residency programme attracting international artists like current resident Max Diallo Jakobsen, whose practice explores the intersections of materiality and the cultural history of Guinea and beyond. LuCAC opened in 2023 with the intention of championing research-based practices rooted in local histories, like the work of Swedish artist Hanna Sjöstrand, whose mid-2025 residency culminated in an exhibition of paintings made from ochre pigments originating from Twin Rivers Kopje, a significant Middle and Later Stone Age archaeological site located in South West Lusaka.

Last year, LuCAC and VAC paid homage to Martin Abasi Phiri with a retrospective of the artist’s personal documents, paintings, drawings and sculptures in LuCAC’s expanded studio space. Viable Visions was curated by Chinese artist and Afro-Asiatic art historian Lifang Zhang, and for audiences who have scarcely experienced the artist’s work in person, the exhibition restored the near-lost archives of one of Zambia’s foremost artists. On display was the Casket Series, including a conceptual installation depicting a self-representation of the artist in a casket made from fluorescent tube holders alongside a video of funeral mourners. The series also revisited the artist’s childhood memory of a colonial mercenary attack during Southern Africa’s independence struggles with a sculpture made from bombshell debris of the incident, unravelling the seams of liberation movements and their reverberations.

Both LuCAC and Everyday Lusaka contribute to the city’s cultural fabric by offering a space for artist development, gatherings and remembrance that extends far beyond the studio. “For a nation of over 20 million people – nearly three million of whom reside in Lusaka – these diverse institutions are essential, yet we are still far from meeting the full needs of the cultural landscape,” says LuCAC founder Mutelekesha.

Such work, moving in and out of archives, piecing together what exists beyond our eyes, reveals the potential of imagined artistic communities. Zambia continues to be generously affected by international influences, who offer hybridity and growth for the arts ecosystem; and yet the collective spirit of the Pan-African freedom fighters who fuelled visions of liberation for all its neighbours is mirrored in contemporary Zambian art practices. Will there come a time when Zambians fully realise the breadth and reach of what Miko termed ‘the octopus’ tentacles’? In times of economic recovery and a void of government funding for the arts, collaborative networks and artist-run spaces remain vital for sustaining and making visible Zambia’s talent.

Read next There is No Such Thing as ‘Real’ Wuxia