Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from the 15th Gwangju Biennale to Manifesta’s arrival in Barcelona

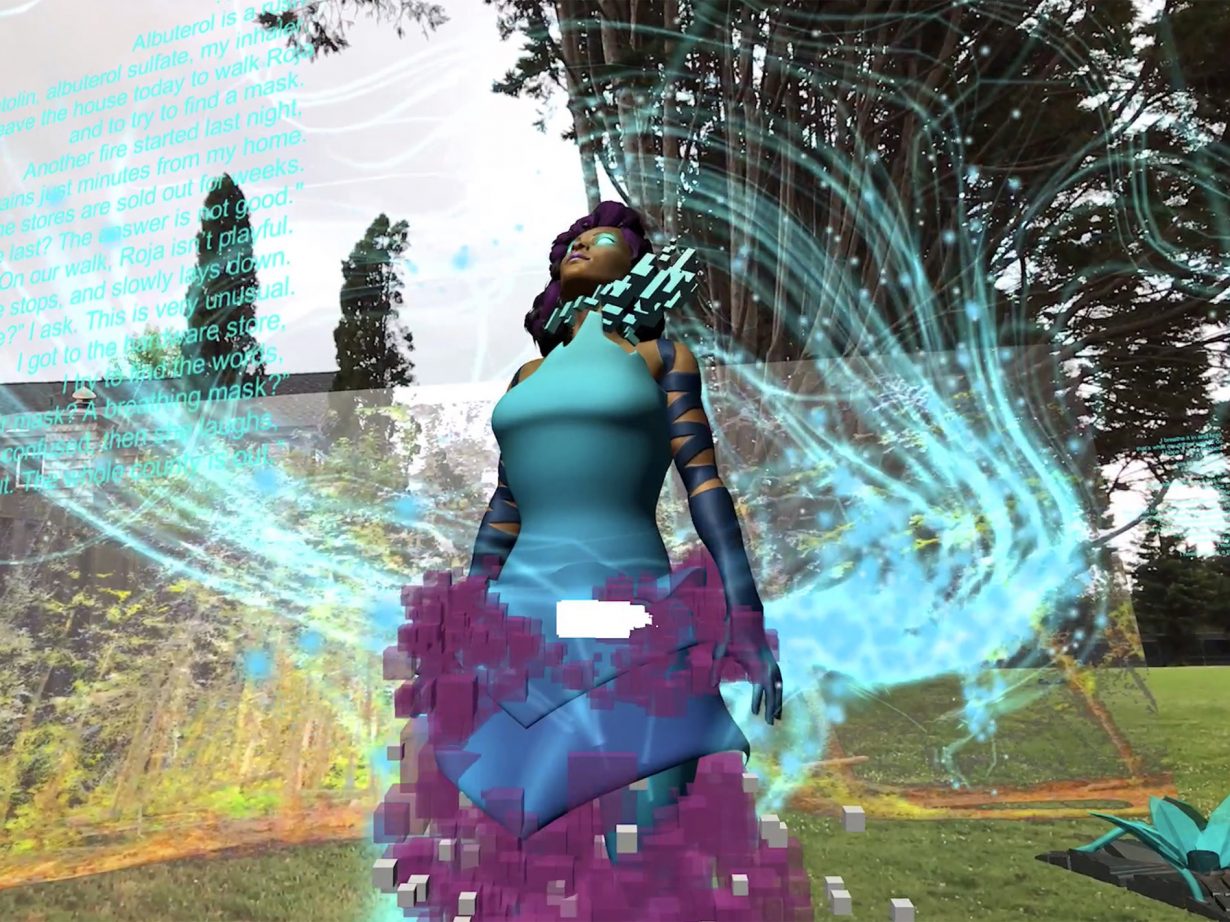

PST ART: Art & Science Collide

Various venues, Los Angeles, 15 September 2024–16 February 2025

The vastly-well-endowed Getty Trust (or just plain ‘Getty’, to you), is an artworld philanthropic heavyweight, which means that when it wants to drop $20m on ‘the largest art event in the United States’, partnering with and supporting over 70 cultural institutions in Southern California, it can. PST ART is the third iteration of what was previously Pacific Standard Time, which Getty initiated in 2011, the first being 2011’s Art in L.A. 1945–1980, an enormous historical review of LA’s postwar artistic dynamism, which was followed by 2017’s LA/LA, a research-heavy project which shifted the frame to concentrate on Latino and Latin American art. This time around, and perhaps reflecting something of the shifting zeitgeist, the capacious rubric is Art & Science Collide. With museums, nonprofits commercial galleries and other organizations all falling into with Getty’s big picture approach, PST ART looks like it’s going to capture practically every going artworld buzz-theme, including sustainable agriculture and climate change, the scientific reimagining of sex and gender, Indigenous and queer sci-fi, artificial intelligence, digital wellness, computer art, electronic surveillance… in other words, it turns out that scientific and technological paradigms (and their alternatives) loom large in how we see ourselves and our possible futures, and artists are hyperactively busy giving shape to those hopes and fears in the present. J.J. Charlesworth

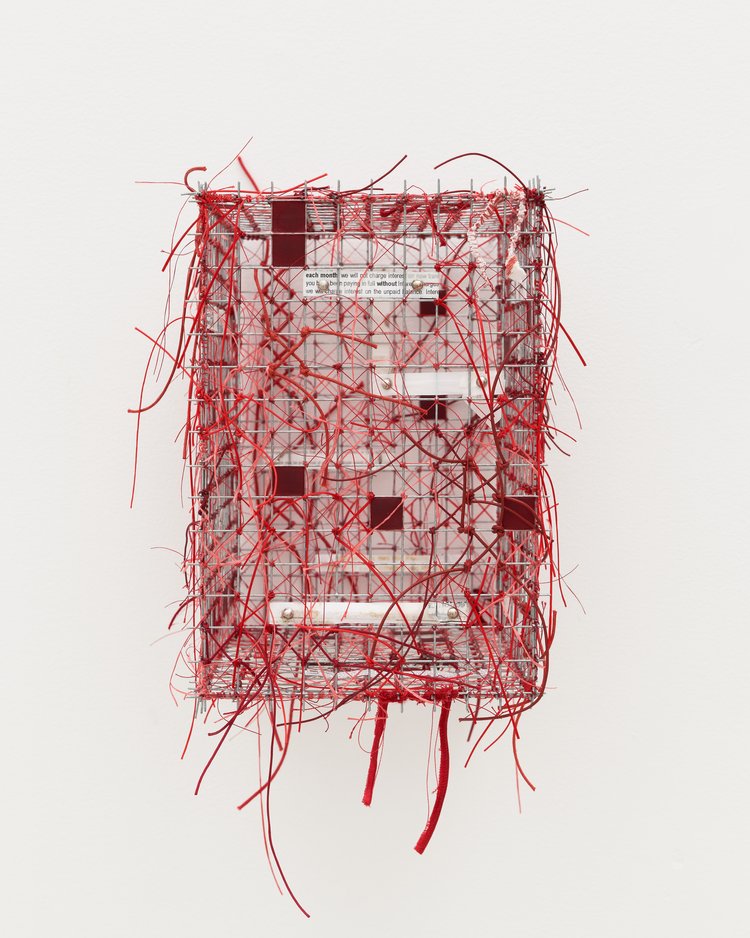

Sylvie Hayes-Wallace: Bleeding

Silke Lindner, New York, 6 September–12 October

Sylvie Hayes-Wallace’s barbed, moody cage sculptures embody the spirit of a generation raised on Tumblr during the global financial crisis. In a solo exhibition at Silke Lindner, she will debut, among other three-dimensional works, a cycle of seven wall-mounted wire boxes she calls ‘head cages’. Meshes of fencing and floss, pieces like Cage (Head) #6 (Bleeding) (2024) and Cage (Head) #7 (Depression) (2024) invoke both the history of this medieval torture device and the visuals of an adolescent’s elastic-laden orthodontics – they appear, in other words, altogether discomfiting and delectably mundane. Within these ornamented grids, made according to measurements of her own cranium, the New York-based artist embeds fragments of personal artefacts as a means of insinuating an identity: a Madonna tank top, a bloodstained mattress protector, a receipt for psychoanalysis… the audaciously long list goes on. Those familiar with Penny Slinger’s Headboxes of the late 1960s and early ’70s might recognize, in Hayes-Wallace’s brand of bricolage-meets-cluttercore, the effort to reconceptualise and reclaim instruments of subjugation with a healthy dose of wit and self-curation. Jenny Wu

-1230x1194.jpg)

The Bamiyan Giant Buddhas: Sun God and Maitreya Beliefs from Gandhara to Japan

Mitsui Memorial Museum, Tokyo, 14 September–12 November

There’s a sad sort of irony to the idea that we suffer from loss because we’re unable to accept the impermanence of the material world. At least, that’s what Buddhism teaches. It’s a cycle that’s hard to break and one that’s seemingly doomed to repeat itself, housed as we are within our material selves. It might seem counterintuitive, then, that The Bamiyan Giant Buddhas: Sun God and Maitreya Beliefs from Gandhara to Japan is an attempt to resurrect the two titular Buddhas and their surrounding murals via drawings, paintings, written records and photographs that were recorded prior to their destruction by the Taliban in 2001. A major focus is Maitreya, considered to be the ‘future Buddha’ (and sometimes referred to as the ‘Unconquerable’), who, it’s said, will only return to Earth after the teachings of the current Buddha, Shakyamuni, are long forgotten. This expansive exhibition traces the history and movement of Maitreya worship across the Silk Road through artworks and artefacts, from sculptures from Gandhara, India, to statues and paintings that have passed through sacred sites in Japan. A feature of The Bamiyan Giant Buddhas is a series of 1:10 scale drawings (based on research gathered by an international coalition of conservationists that included Tokyo Research Institute for Cultural Properties) that recreate the Bamiyan murals, which are on show for the first time in Japan. Another irony: that this exhibition only adds to the delay of Maitreya’s arrival perhaps means that we’re not quite ready to accept such losses. So, round we go. Fi Churchman

Legacies: Asian American Art Movements in New York City (1969–2001)

80WSE, New York, 11 September–20 December

Given that this survey of over 90 artists and collectives of Asian descent is taking place in New York City, the ground zero of American identity politics, it is perhaps noteworthy that the curators of Legacies seem uncomfortable with the task of defining what Asian American Art might be. ‘Recognizing that “identity-based” categories of art are bound to the dominant racial ideology and political narrative of a nation, the exhibition instead focuses on a multiplicity of subjectivities, political horizons, and artistic expressions to interrogate life in America,’ write Howie Chen, Jayne Cole and Christina Ong. The evolution of the term ‘Asian American’ is traced from its inception as a progressive political identity in 1968 by UC Berkeley’s Asian American Political Alliance through the studios of artists such as painter and glassblower Arlan Huang, speculative fiction new media maker Mariko Mori and photographer Tseng Kwong Chi, alongside new commissions from the likes of Shu Lea Cheang and Rea Tajiri. Luc Querry

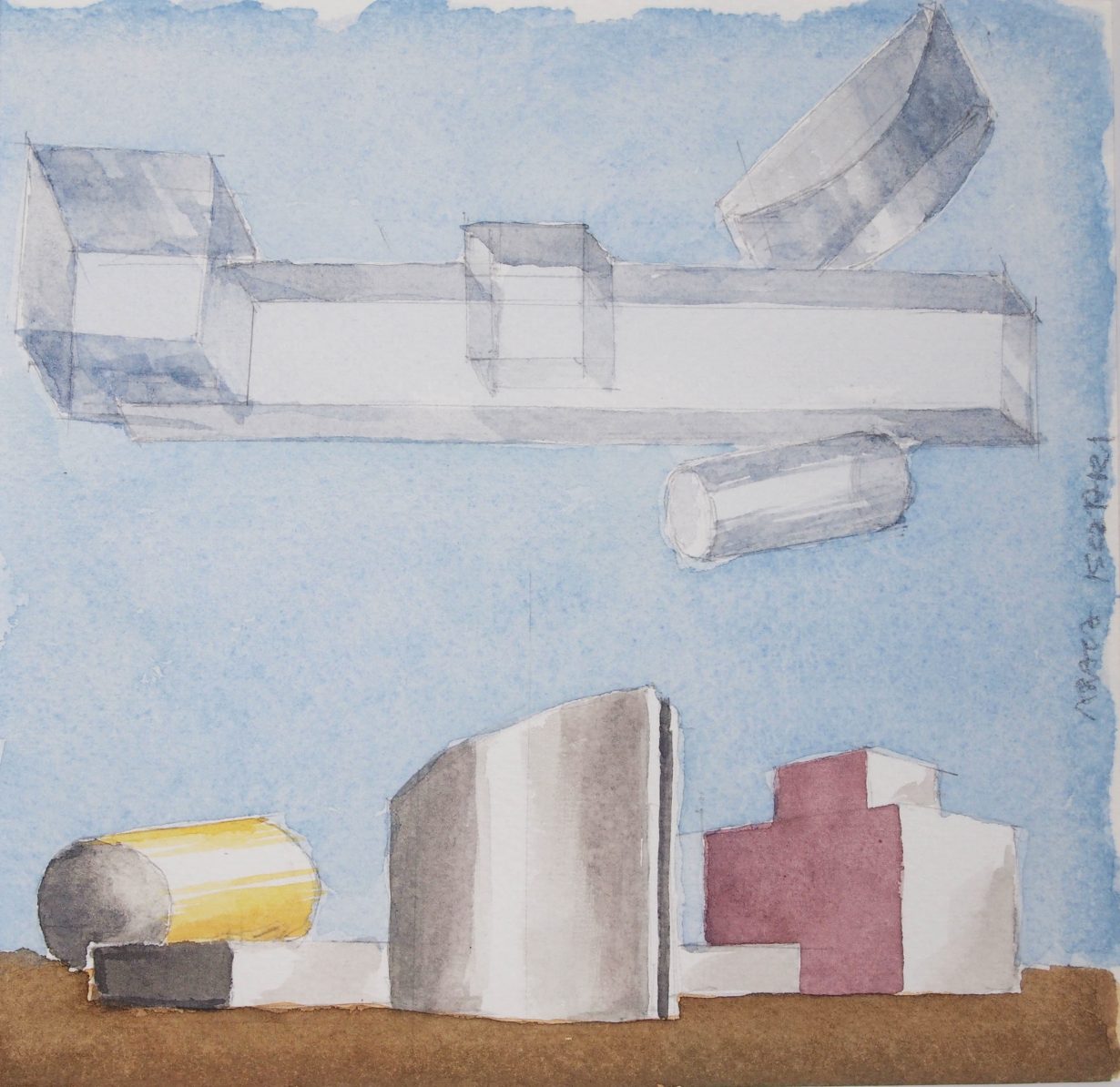

Forest Festival of the Arts Okayama

Various venues, Okayama, 28 September–24 November

Ever wanted to see Rirkrit Tiravanija’s work in a seventeenth-century landscaped garden, or an Anri Sala sound installation in the depths of a limestone cave? From forest parks to folk museums, the contexts and locations almost outnumber (even take precedence) over the 36 artists participating in the Forest Festival of the Arts Okayama. Spread over more than 20 locations in and around Maniwa, Nagi and Niimi, across the northern part of the Okayama prefecture, in the southern central part of Japan’s Honshu island, the festival bears the subtitle of ‘clear skies country’, promising considerations of sustainability, biodiversity and landscape, if not good weather. The scope of the works being displayed over this two-month period is striking, ranging from performance to architecture, from the sound installations of Tarek Atoui and Aki Inomata’s Thinking of Yesterday’s Sky (2022) project, where 3D-printed cloud-shaped liquid is placed in glasses of water that visitors are invited to drink, to the work of architect Arata Isozaki and the neon-lit punk-noir photographs of Mika Ninagawa. Chris Fite-Wassilak

15th Gwangju Biennale

Multiple venues, Gwangju, 7 September–1 December

If the last edition of Gwangju Biennale – opened just last year after being postponed by the pandemic – Soft and weak like water was about the gentleness, endurance and resilience of this fluid matter, its 15th edition, tilted Pansori: A Soundscape of the 21st Century, is about something more amorphous: the saturated, meandering polyphony of sound. Curated by critic and author of hot terms such as ‘altermodernism’ and ‘relational aesthetics’ Nicolas Bourriaud, the exhibition builds on the central idea that ‘landscapes are also soundscapes’, borrowing from the Korean music genre pansori which literally means ‘the noise from the public place’. Walking through the exhibition’s three chapters ‘The Larsen effect’, ‘Polyphony’ and ‘The Primordial sound’ will be an experience in which a densely crammed, cacophonous soundscape – ‘a world saturated with human activities’ where ‘both interhuman and interspecies relations become more intense’ – gradually opens up into ones that are more sparse, revealing the unheard and the infinitely small in a multi-focused world. On view will be 72 artists from 30 countries, including Emeka Ogboh, Josèfa Ntjam, Na Mira and Mimi Park, to name but a few. Yuwen Jiang

Manifesta 15

Various venues, Barcelona, 8 September–24 November

Following its 2022 edition in Prishtina, the nomadic biennial Manifesta’s fifteenth edition crosses the continent to Barcelona and its wider metropolitana. This year’s programme siphons into three ‘clusters’, or acts: ‘Balancing Conflicts’, ‘Cure and Care’ and ‘Imagining Futures’. Though it’s safe to say that its subject, as with many previous Manifesta editions, is its host geography. ‘Balancing Conflicts’ begins on the Llobregat Delta nature reserve, which has been losing ground to urbanisation and planned airport expansion, and a modernist villa entwined with the region’s cultural history. Industry versus culture et cetera. ‘Cure and Care’ revolves around a ninth-century Benedictine Abbey in the Collserola, Barcelona’s green lung to the north, while ‘Imagining Futures’ heads down the Besòs River to the rather surreal Three Chimneys of Sant Adrià. A former power-plant in the densely-populated suburbs between Barcelona and Badalona, its three, wide-based spires sit like walkie-talkies in their docking station. The Coco beach waves will be accompanied by Félix Blume’s sound design; the nearby panoptic Mataró prison will be populated (with art) by Korakrit Arunanondchai and Maya Wanatabe, among others. All this new-geohistoricism – ‘activating’ the past through the interpretation of locations (for which Manifesta 15 is not alone) – vests a lot of faith in the artists placed within them. While their curators sit back and ask us to imagine the future, artists will have eighty days to show us what is possible. Alexander Leissle

Ayesha Sultana

Ishara Art Foundation, Dubai, 6 September–7 December

Breathe in, breathe out; breathe in, breathe out. Such is the rhythm necessary for existence. This fundamental activity runs through Ayesha Sultana’s exhibition Fragility and Resilience, the Bangladeshi artist tracing breath both as a physiological mechanism and a process that inextricably links each of us with all living beings. Such existential ponderance is introduced by Sultana’s handblown glass sculptures (displayed for the first time) – the artist’s exhalation gives each work its final form, resembling droplets of water. In the Breath Count series (2018–), Sultana has scratched marks of varying size onto tablets of clay-coated paper, keeping count of her inhales and exhales as she makes the work. This tabulation is brought into sharp focus in Threshold (2012–13), a series created to commemorate the death of Sultana’s father in 2008, which features photographs he took during his assignments as an officer of the Bangladesh Air Force, their surfaces scratched and solarised by the artist. Luc Querry

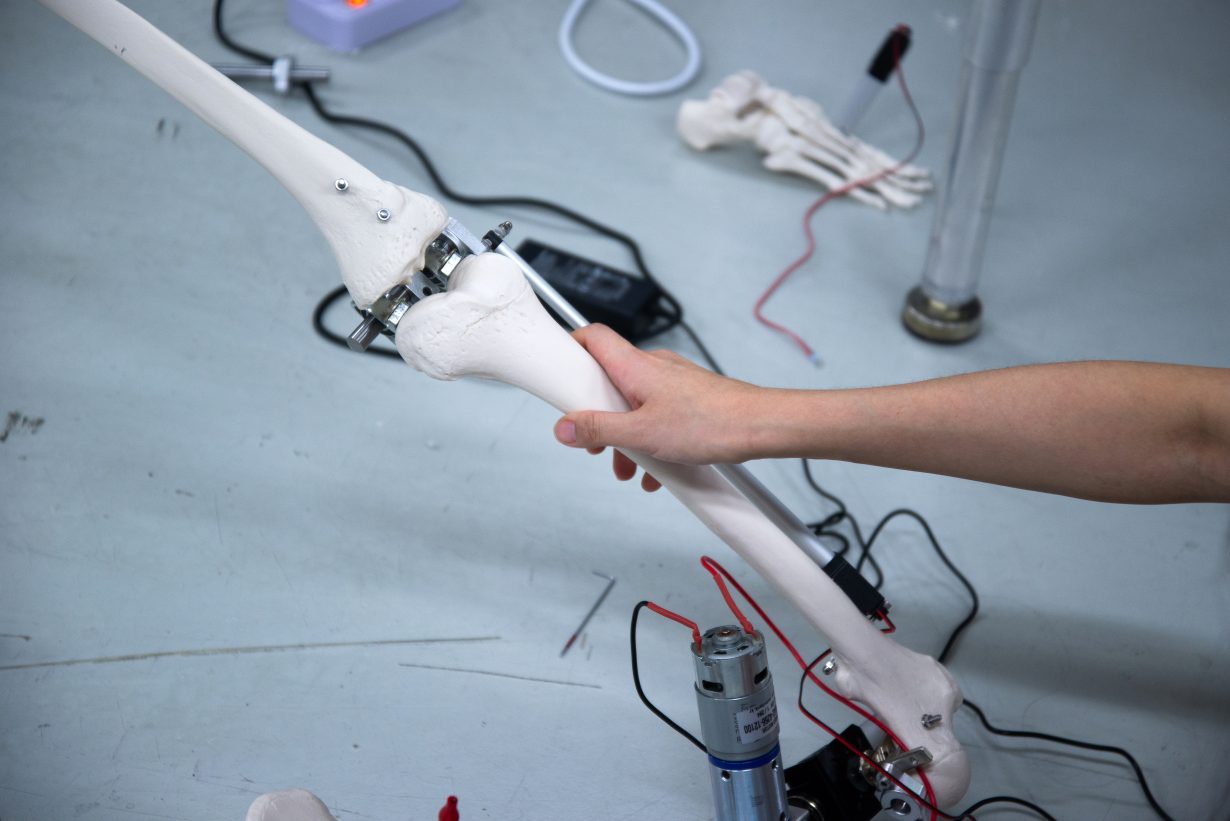

Geumhyung Jeong, Under Construction

Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 25 September – 15 December

Some people collect stamps or sneakers; Geumhyung Jeong collects bodies. The South Korean artist and choreographer is an eerie puppeteer of inanimate limbs and torsos, vacuum cleaners and latex gloves. Under her direction, anatomical models and everyday objects alike come alive in bizarre, at times humorous performances featuring Jeong herself, who animates her vast ‘collection’ of objects with a force of personality that manages to be both breezily quotidian and brazenly surreal. Under Construction, as her latest exhibition at London’s ICA is titled, suggests a site in the process of being built, or a loading bar creeping gradually to completion. Jeong’s interest in robotics offers a framework with which to understand the human body as a machine that is continuously being remade, reconstructed and (increasingly) improved upon. Here she incorporates human skeletons alongside mannequins and technological hardware in hybrid sculptures that stumble and falter between the uncanny and the ridiculous, or flicker knowingly between the two. With a background in acting, she has an eye for the social fronts and facades of, say, a group of strangers standing together at a party. It is these subtle visual cues and emotional tics that she is able to translate to the jerky movements and sensual gestures of her deconstructed figures, imbuing them with a palpable sense of agency that at times feels more convincing than their real human counterparts. It is a sideways look at our increasingly entrenched relationship with technology, one that is as absurdist as it is uncomfortably believable. Louise Benson

Ancestral Treasures of Peru

CCBB, São Paulo, 4 September–18 November

The Gold Museum of Peru and Arms of the World in Lima is an institutional wonder, full of beguiling treasure of the ancient world. Yet for all its mesmeric shimmer, a shadow of tragedy hangs (a violence suggested in the second part of the name). The museum is not just a testament to pre-Columbian civilisation, but also to the sculpture, religious icons and jewellery that were stolen and more often melted down in the hands of invading Europeans (beginning with the ransom – enough gold to fill his cell – paid by Atahualpa, emperor of the Incas to his Spanish captors in 1532). Since then the Peruvians have been rightfully protective of their trove, but now 162 objects from the Lima institution’s collection – tapestries and ceramics alongside the shiny stuff – is touring Brazil, the show arriving in the São Paulo headquarters of Banco do Brasil from Rio de Janeiro (so they should be nice and safe from modern-day sticky fingers), before travelling to the bank’s cultural centres in Belo Horizonte and Brasília. The venue is a choice reminder too that these treasures, which include a sacred knife used in sacrifices, a silver cup in the form of a llama’s head and a golden figure sporting platinum pair of pants – were a mode of currency too, a time and culture in which trading was a lot more aesthetically interesting than a tapping a contactless bank card. Oliver Basciano