The exhibition has cunningly critic-proofed itself

When, in recent years, the curatorial reins of the Berlin Biennale have been handed to artists, the results have been single-minded and, consequently, divisive. For the seventh edition, in 2012, Artur Żmijewski delivered what frequently felt more like an activist sit-in than a show; for the ninth, in 2016, artist collective DIS spotlighted post-internet art to the point of killing it via overexposure. This year’s exhibition Still Present! – curated by Kader Attia and an ‘artistic team’ comprised of Ana Teixeira Pinto, Đỗ Tường Linh, Marie Helene Pereira, Noam Segal and Rasha Salti – is unabashedly committed in a different way. It relentlessly addresses, from a multitude of angles, what the French artist described in the opening press conference as “the blind spots and unthought sides of western modernity and its correlatives – colonialism, slavery, imperialism”. Spread across six venues and largely avoiding marquee names, the show serves as a global tour of iniquities (and their entwined historical roots) that might be classed as ‘invisible’ to western art audiences; and as an omnidirectional call, and showcase, for decolonial practices.

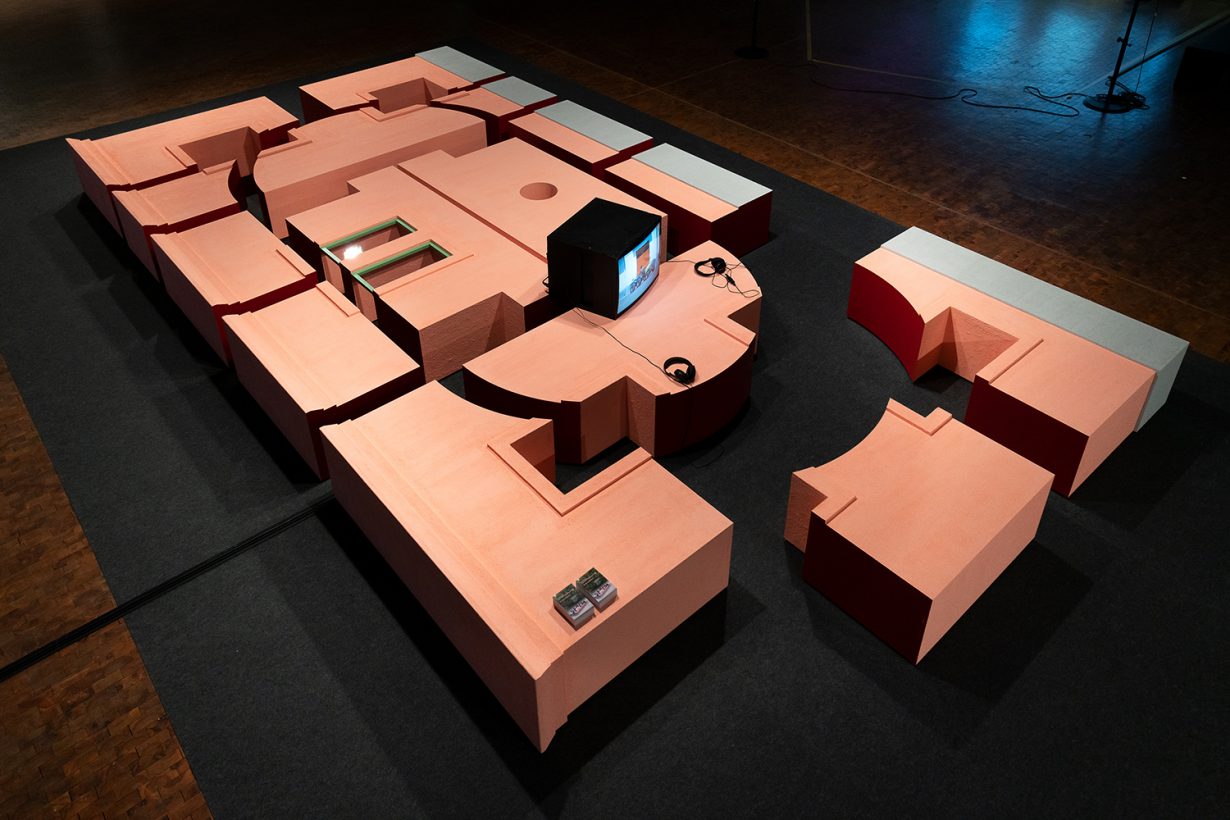

Take, for example, the 19-artist-strong presentation at the western outpost of the Akademie der Künste. In short order, one encounters Imani Jacqueline Brown’s video installation filmed in Louisiana’s industrially polluted and disintegrating coastal wetlands (known colloquially, among other things, as ‘cancer alley’), which are also a site for environmental activism; Mai Nguyễn-Long’s unnerving double shelf of specimen jars containing dolls and toys – referring back to the US military’s use of the herbicidal weapon Agent Orange in the Vietnam War, which caused widespread sickness and birth defects as well as environmental devastation; Forensic Architecture’s video exploration of toxic clouds and state power, from tear gas used against anti-fracking protesters to the poisonous smoke in the Grenfell Tower blaze, to chlorine chemical gas attacks in Aleppo; and artist group DAAR’s film about the discussion-based decolonisation of fascist architecture in Sicily. Amid much documentarian moving-image work that pulls the viewer along at its own pace, you might end up pausing to gather yourself in front of Tammy Nguyen’s vivid, green-and-gold-hued paintings, since they stand still. These, though, turn out to be inspired by a Catholic park in a Vietnamese refugee camp on the Indonesian island of Galang, containing gold statues representing the Stations of the Cross, and here Christ-as-coloniser is engulfed unhappily by a tropical landscape dotted with crashed American aeroplanes. Break over; back to a video (by Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn) about how badly humans treat animals.

Various wings of the show, it appears, have their own distinct emphases, delivering structure to Attia’s compound broadside. At KW Institute for Contemporary Art, more stress feels placed on occluded women’s histories and present-day activism. Half-buried horrors, as in Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s expansive image-text presentation pointing to the mass rapes that occurred in Berlin at the end of World War Two, are set against lesser-known heroism, as in Zuzanna Hertzberg’s archival display addressing organised and autonomous women’s resistance during the Holocaust, or local activism such as Jeneen Frei Njootli’s arrangement of flags and freestanding plywood cutouts (described as ‘altered traditional objects’) pointing to her participation in an Indigenous women’s art collective in the Yukon, and the subject of displaced communities. At the other, more central branch of the Akademie der Künste, the focus swings more emphatically to colonialism via a central display of wooden Christian artefacts from across Africa, made by ‘unidentified artists’, dating from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and surrounded by ‘exotic’ paintings by German modernists Emil Nolde and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Nearby, Moses März’s hand-drawn flowcharts, intricately tabulating myriad aspects of colonial power and resistance to it, might strike one as a cipher for the whole curatorial project, not least in its capacity to quickly overwhelm via complex interrelation.

Not all the venues hit so cleanly. The display at the Hamburger Bahnhof, not quite fully installed during the press viewing – cue a lot of hydraulic platforms and scribbled labels on masking tape – is a long, incoherent corridor punctuated by Jean-Jacques Lebel’s gratuitous-feeling roomful of blow-ups of the notoriously grim photographs taken by American soldiers at Abu Ghraib. If, meanwhile, one schleps out to distant Lichtenberg to see the segment at the former Stasi HQ, now a museum, it feels like a long way to go for seven artworks, bad ventilation and some surly museum staff. By that point, though, and assuming you go there last, less might feel like more and vice versa. Finishing up and encountering people who’d just begun, this viewer repeatedly heard anxious variations on “is it all this dry?” Well, yes, pretty much. The problem with saying so, or naysaying at all, is that in many ways Attia’s exhibition has critic-proofed itself; the typical affluent biennale-goer can’t complain righteously about having to observe the toxic network effects of western modernity; or about being shown, via artwork after artwork, how widespread and entangled those effects are. The most they might say, aside making the ‘that’s not what art is for’ aestheticist argument, is that the show courts ye olde compassion fatigue, to which one response might be: take it more slowly, linger on the examples of positive restitutive work already being done. If you want affable art, there’s plenty of that in commercial galleries.

It feels fitting that an artist, a maker of things, should construct a biennale that feels as much like an entity as this one, for all that it is composed of many parts. That entity, it strikes one, doesn’t much care about making nice or being liked, or giving viewers an easy ride. After all, nobody else in the real-world conditions it points diversely towards is getting one. Rather, Attia here proceeds from a position of inarguable urgency, one which the constituents of his show restate over and again, and a bedrock hopefulness regarding change. As such, if this isn’t the biennale we want, it might nevertheless be the type that we need.

Berlin Biennale, various venues, Berlin, until 18 September