The composer who put bombs under the cosy certainties of British new music

The afternoon I arrived at Harrison Birtwistle’s house in Mere, Wiltshire, in 2010 to interview him about a new disc of some recent orchestral works, he had spent all morning nudging ideas around the page, getting nowhere fast, for a new solo piano piece, which subsequently he called Gigue Machine (2011). “There’s one aspect of this new piano piece I’m very clear about,” he explained, “but making the piece happen is very difficult. Applying solutions that are already there is an easy way out…[but] when music starts to write itself, that can be dangerous too, because you can lose awareness of the material. So, on one hand, composing is impossible, and on the other it’s too easy.”

Looking back at that interview now, I’m struck by the range of reference points Birtwistle served up that day. This composer, apparently the Modernist everyone must fear, the man who put bombs under the cosy certainties of British new music, talked to me about Beethoven, John Dowland, Albrecht Dürer and Paul Klee. He kicked back my opening question – about early pieces of his like Tragoedia (1965) and The Triumph of Time (1971) – with the line “I’m sick of talking about this. Can’t you get if from somewhere else?”, words delivered with perfect comic timing. For a man with so much to say about the art, and about the process of composition, Birtwistle could seem reluctant to go there. Theories have been spun about how he wrestled Tragoedia – his breakthrough work, written for a mixed ensemble of wind and strings – out of the influence of Anton Webern, Edgard Varèse, and Iannis Xenakis. But the most Birtwistle would tell me: “the things that work in that piece just sort of happened.”

Analysing things that “happen”, the danger is that they might stop happening; you jinx them. Birtwistle’s reluctance to dive too deeply into the ‘hows’ and ‘whys’ of composition was, I think, partly to do with that; and also the fear that the second you nail down any truths or certainties, that’s the moment the music itself will move on. Yet, he loved to talk. I quickly learned to aim my questions away from the note-by-note specifics of his own work. Probing more general ideas was a sure way of striking gold.

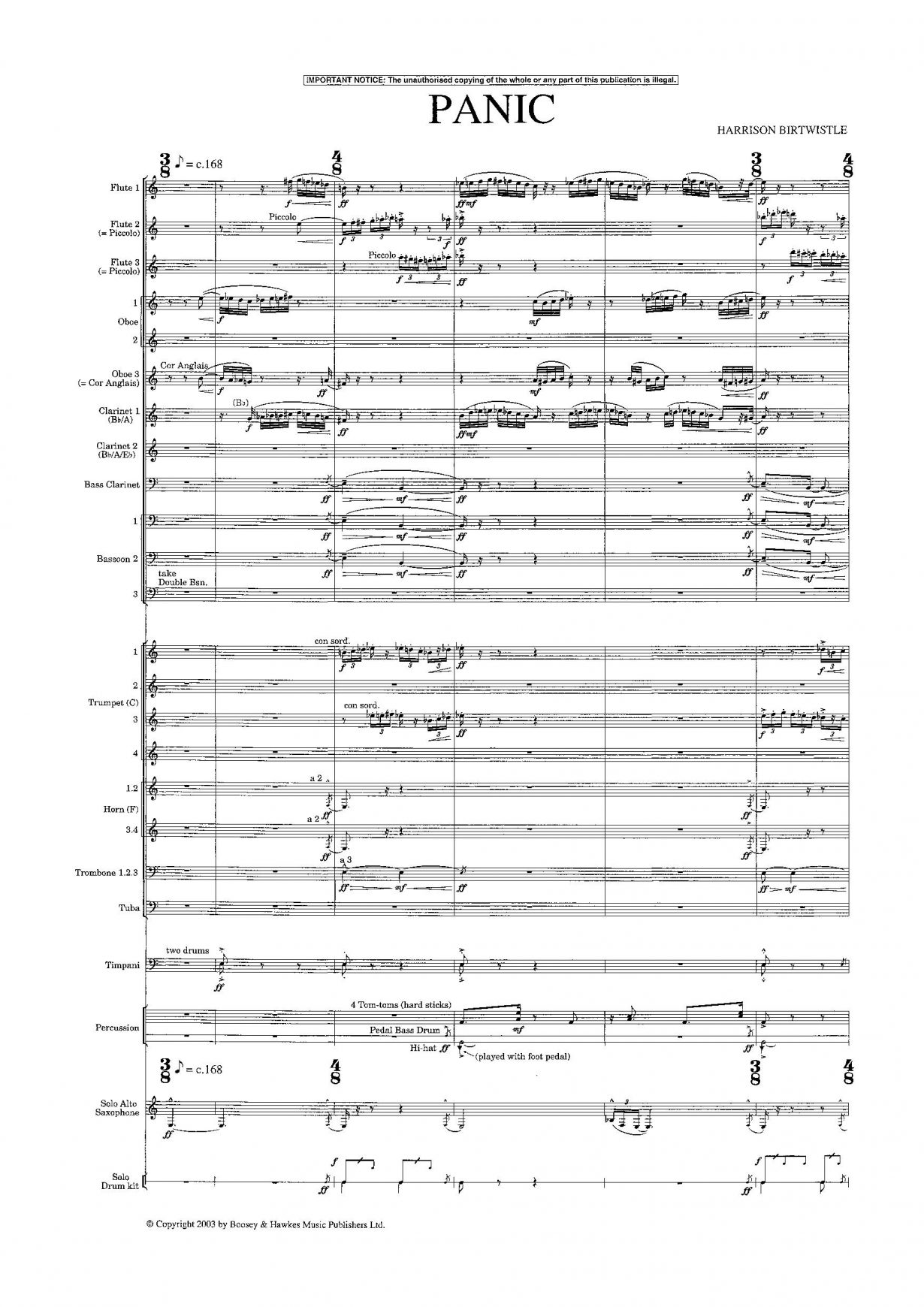

The compositions which made his name – including his orchestral Earth Dances (1986), Melencolia I (1976) for clarinet and strings, his opera The Mask Of Orpheus (1986) and Panic (1995), for saxophone, drum kit and orchestra, a work which put the wind up the audience of The Last Night of The Proms – were all monolithic essays about cyclic time. Birtwistle was obsessed with ritual and myth; with works that inched forwards across time by viewing the same essential idea from many different perspectives, sometimes all at once, sometimes sequentially. Schoenberg’s 12-tone harmony had proved useless to him while he was still finding his compositional feet. “It couldn’t produce the harmony I wanted,” he told me, “like trying to make a figure in clay that should have been in wood. Is the music being expressed through the tone row? Or the tone row being expressed through the music? I discovered I couldn’t care less either way. I was interested in the music in my head.”

One point of departure, he told me, towards finding a language to call his own was the delight he took in exploring music of the English Renaissance. Shadow of Night (2001), on his new orchestral disc, unfurled out of a three-note cell borrowed from John Dowland’s song In Darkness Let Me Dwell (1610). “There’s a lyrical expression in Dowland that isn’t like anything else in music,” he explained. “It shows itself again in Purcell, then disappears.” Later, as we discussed the violin concerto he had just completed, Birtwistle said “lyricism has to run deeper than lyrical melody.” He spoke of how a “lyric quality” could percolate through soloist and orchestra, with lines travelling through space “like airplanes have flight paths.”

The tradition into which Birtwistle slots most neatly, perhaps, is that of English empiricism. Stockpiling pre-learned technique then finding the music he wanted to write was of zero interest; rather he found the technique he wanted through the process of constructing each piece. The sounds inside his head did include formative models from Stravinsky, Messiaen, Varèse, Tippett and Stockhausen, yet the project was always to compose a world of his own. Coming home from Mere after my afternoon with Birtwistle, I thought of Stonehenge, those ancient monoliths walloped into the Wiltshire countryside for reasons that will forever exist in the realm of speculation, abstract shapes which could equally have been made by Jacob Epstein or Barbara Hepworth. That was Harrison Birtwistle’s world, too.