The Chinese artist gathers together artefacts from across time to interrogate the fine line between technological advancement and political control by design

This is Ai Weiwei’s first major solo exhibition in the UK since his 2014 retrospective at the Royal Academy, which opened when Ai’s passport was still being held by Chinese authorities following his arrest and detention. While many of Ai’s previous exhibitions have been overtly political both in terms of their content and context, the Design Museum seems to offer a more neutral ground upon which the artist has felt able to return to the formal and material building-blocks of his practice, exploring the affordances between authenticity and appropriation, form and function, making and meaning.

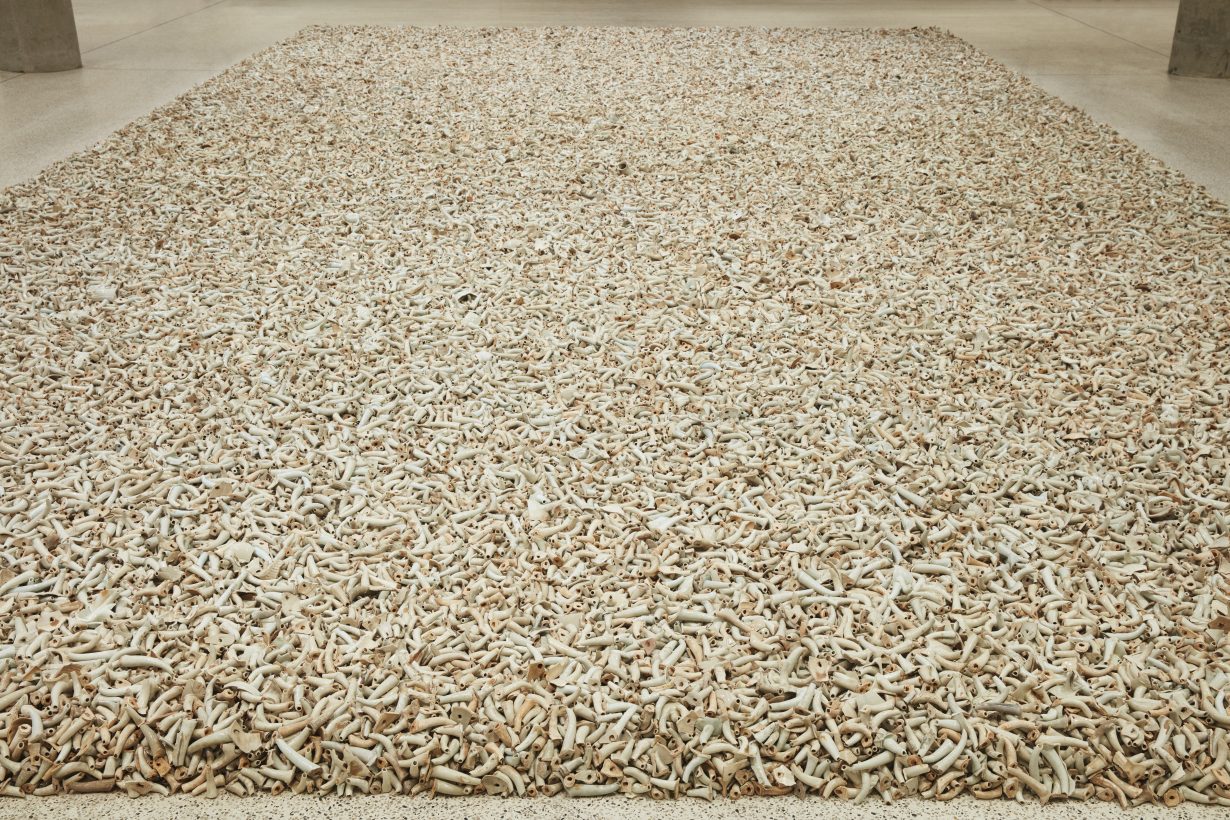

The exhibition takes place in a single room – the expansive space of the main exhibition hall – which is divided into five discrete ‘fields’ of accumulated objects, ranging from thousands of arrowheads and tools apparently dating from the Stone Age, neatly displayed like artefacts unearthed from an archaeological site; to a garish explosion of plastic Lego bricks, donated by members of the public after the transnational corporation stated that it was against company policy to supply their product for political works. The other fields are populated with a curious assortment of weaponry, castoffs and fragments: some 200,000 ceramic cannonballs crafted during the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE); a concatenation of bonelike teapot spouts also fabricated during the Song period, severed and discarded due to minute imperfections in the manufacturing process; and a jagged sea of blue-and-white porcelain shards from one of Ai’s artworks, destroyed when his studio in Beijing was razed by Chinese authorities in 2018 without warning. These objects prompt us to reflect on ambivalent patterns of creative expression and suppression, standardisation and variation, and the dignity of labour and its exploitation.

As the art historian Lothar Ledderose has argued in his book Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art (2000), some of the most remarkable examples of Chinese art, architecture and design over the course of millennia were made possible by the early development of modular systems: the mass fabrication of standardised units that could be reassembled into myriad configurations of form and function, producing objects in large quantities and of great variety. The most famous example of this is the Terracotta Army of the First Emperor Qin Shi Huang (259–210 BCE) consisting of several thousand lifesize sculptures assembled from a fixed repertoire of cast body-parts and individually finished by hand. It’s testament to the wonders of China’s technological advancement, artistry and innovation, but also a rigid, underlying infrastructure of political and social organisation, and control by design.

The surrounding wall space has been thoughtfully utilised to provide further context in this regard, displaying examples from a range of photographic series (some of them never exhibited before) that centre on the remarkable urban transformations in Ai’s native city, Beijing, to which the artist has not been able to return following his political troubles. Beijing Photographs (1993–2003) takes us back to the period when Ai made his famous triptych Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995; in which the artist appears to drop the antique vessel, which smashes on the floor), documenting the artist and his brother’s numerous visits to flea markets filled with antiquities, some real, some fake, from which many of the objects on display were acquired.

Provisional Landscapes (2002–08) features rubble-strewn voids in the urban fabric: all that remains of the traditional dwellings and silenced communities swept away by the tide of China’s rapid modernisation and development. National Stadium (2005–07) chronicles the construction of the symbol par excellence of China’s growing presence on the world stage in preparation for the watershed 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, which Ai designed in collaboration with Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron. Captured in various stages of completion, the stadium appears like a ruin in reverse, dramatising the fate of so many of these aspirational monuments of state power and spectacular infrastructure over the course of human history. Elsewhere we find other remains and part-objects – sometimes cast in different materials – that range from ordinary household items to the steel rebar and children’s backpacks that Ai salvaged from schools that collapsed in the wake of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake; a natural disaster that formed the basis of Ai’s citizen investigations into government officials who had siphoned money from building materials, resulting in the senseless death of thousands of people.

Amidst the multitude of things on display, another portrait of Ai emerges – that of the artist as collector, bricoleur or, perhaps more intriguingly, hoarder. Nothing is discarded, and every object no matter how small and fragmentary has the potential to be repurposed, reframed and recombined into a new artistic assemblage. In this, Making Sense is an exhibition that prompts us to think about the ways in which art might intervene in and reconfigure what Jacques Rancière called the ‘distribution of the sensible’ – the laws, systems and structures of power in a given community that determine who has the right to be seen and be heard, to do and make.

Making Sense at Design Museum, London, through 30 July