“As you get older, you kind of know what you’re doing, but it doesn’t mean your pictures are going to be better. You just know when you have it and when you don’t.”

As her latest exhibition opens at Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong, ArtReview revisits a 2019 interview with the American photographer in which she discusses watching Warhol at work, colour pictures, the commercial world of magazines, and being “a conceptual artist using photography” (as told to Fi Churchman).

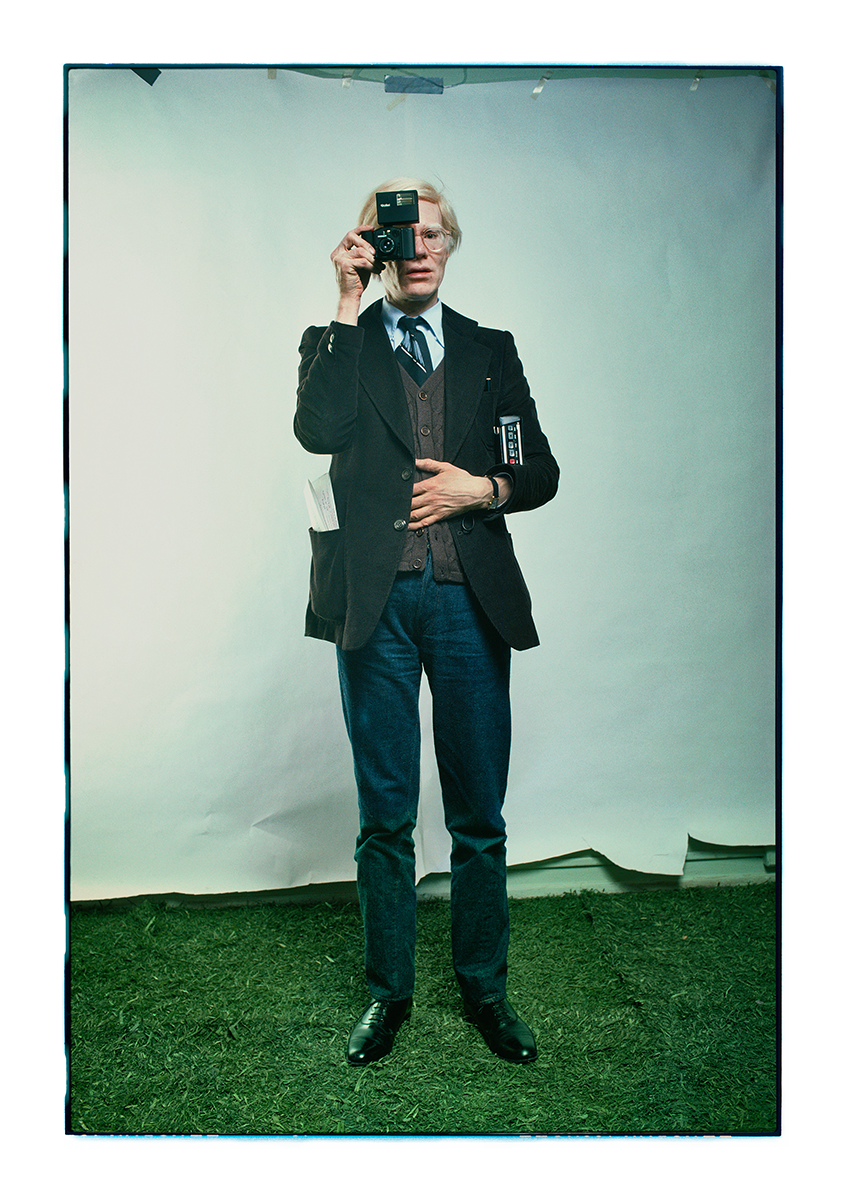

I remember going to the Factory in 1976 and watching Andy Warhol work. I’d been there before, earlier in the 70s, photographing Joe Dallesandro and Holly Woodlawn, and then Paul Morrissey. Warhol was a fixture of New York. It was just shocking when he died, because he was everywhere. I don’t know how he did it, but he was out at everything. You felt that if he was at a place you were at, then you were at the right place.

Warhol had things everywhere in the Factory – silkscreens all over the place, and tables of artwork – and things were always going on. I think Fran Lebowitz was there for Interview magazine, and [Warhol] was photographing the sisters from Grey Gardens [1975]. I was just a fly on the wall: there were people milling around doing all kinds of things, it was a pretty active place.

He had a roll of paper hung up that he would take photographs against. It had a jagged edge and I just said, “Stand over here”. The shoot was easy. Warhol was always nice, always gracious, always wonderful. I hate to put it like this, but he was always giving you something. He would pose for you. He’s photogenic, with the hair, and he was always holding a tape recorder or camera or something. What’s nice about that picture is that it’s practically nothing. It’s just him.

If there’s anything interesting about that photograph it’s how crudely it’s lit. It just looks like a hard strobe light. We went with this picture because it was a little off and a little weird. I liked the light. It’s very graphic. He’s straightforward and it’s a very simple presentation. I love the Astroturf and the torn paper. He’s pointing a camera back at me because that’s who he is. He recorded and took pictures all the time. As a photographer I like the strangeness and colour and simplicity.

It was the beginning of my colour work, which at that point was pretty crude. I didn’t really know how to take colour pictures. I first used colour when I took photos of Marvin Gaye on a mountaintop at sunset for a Rolling Stone cover and you couldn’t see him – I used natural light, not a strobe, and he just sort of blended into the background! It was a beautiful photograph but it was very subtle, and because it was printed on the Rolling Stone’s rag paper, everything sort of went muddy. That’s when I started to strobe things. I just threw up one light and aimed it towards the subject. I think all my work from the mid-1970s until I left Rolling Stone and started to work for Condé Nast in the early 80s had very crude colour: I had no idea how bright it was until we printed a book in 1983. I was over-lighting everything so that it would survive being printed in Rolling Stone.

Having gone to a fine art school in San Francisco and studied Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank, I worked in that style. But by the mid- to late 70s I was starting to look at fashion magazines from Europe, at the works of Guy Bourdin and Helmut Newton, and other kinds of photography that started to inspire and enthuse me. Diane Arbus was also very important at that point for me.

Doing the covers for Rolling Stone, I learned how to use the vertical format, but I’m not a big fan of vertical photographs. I think I can count mine on one hand. I always liked being a little further away, seeing the subjects of my portraits in their surroundings. It took me years to come in closer. When David Hockney did his photomontages [the series Joiners, early–mid-1980s] I became weak in the knees, because that is how you really see. It’s hard to put what you see into a rectangle, whether vertical or horizontal, but with Hockney’s photomontages – a great study in perspective – you see to the left and the right. I just did a series for Google where I used two pictures to make a portrait. One picture was a little closer in – a typical portrait – and then I pulled away and photographed either an object or a landscape, something that meant something to that person. One photograph is not going to tell you everything about a person. We’re complicated.

I chose to call myself a portrait photographer because labels were always being thrown on me. When I was at Rolling Stone I was a ‘rock-and-roll photographer’, at Vanity Fair I was a ‘celebrity photographer’. You know, I’m just a photographer. I realised I wasn’t really a journalist. I have a point of view and, while these photographs that I call portraits can be conceptual or illustrative, that keeps me on the straight and narrow. So I settled on this brand called ‘portraits’ because it had a lot of leeway. But I don’t think of myself that way now: I think of myself as a conceptual artist using photography.

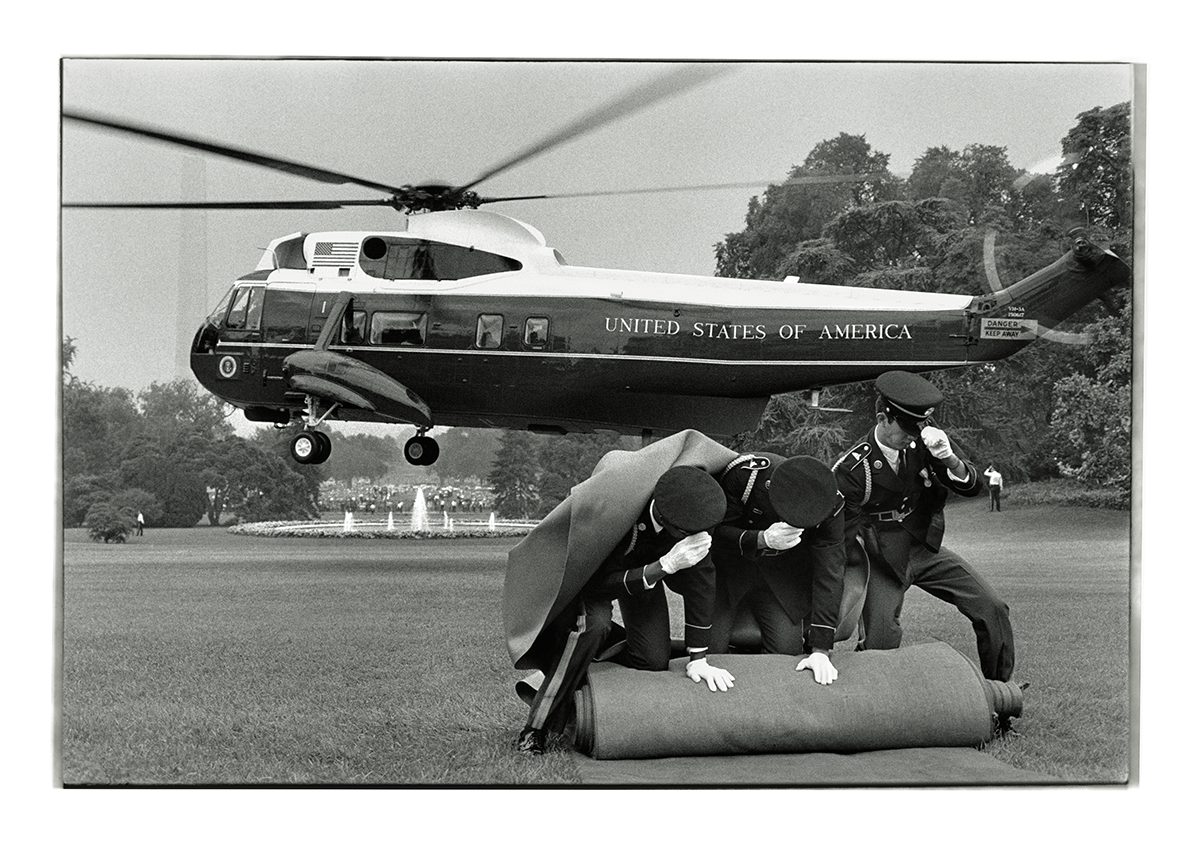

The photographs take on a different life as the years go by. At Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong, there are photos from 1970 to 1983 (up until I joined Condé Nast), selected from a very large show in Arles, at the Luma Foundation. That show in Arles allowed me to see myself as that obsessed young photographer, living with a camera every single day. I always had my camera! I’m really proud of that period. I took a chance and went into this commercial world of magazines as a landscape in which to take photographs. The tension in my work is working for these places and trying to do good photography. In that period there were a lot of photographs that were not very good and there were some that transcended it. Rolling Stone really didn’t have any idea either… so we grew together. The first time they gave me spreads – those pictures of Richard Nixon leaving the White House – was because Hunter Thompson never filed his piece on the resignation. He had a block. So they ran eight pages of my pictures instead. Rolling Stone became more interested in photography as things went on.

I wanted with that show, and with the subsequent shows at Hauser & Wirth [a version of the Hong Kong exhibition was presented at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles in 2019], to overwhelm the viewer just by showing how much work was done. I was relentless. I try to assure young photographers now not to worry about it, that they’ll come out of it. As you get older, you kind of know what you’re doing, but it doesn’t mean your pictures are going to be better. You just know when you have it and when you don’t.

The exhibition is called Archive No. 1 because it’s not a retrospective or survey, it’s the first time I’ve gone back to that era. I’m still a working photographer, and I’m not ready to use ‘retrospective’. I’m getting close but I’m not there yet. This is a first look at those earlier works. I’m shooting with a 35mm camera, and you can see the process of moving from the ‘studies’ or ‘sketches’ of a young photographer, who’s looking all the time, to portrait work, which comes from observation. If I have a ‘trick’ to taking portraits now, it’s to not make it a long process. I’d rather come back. My best photographs are of family and friends, because they put up with me. I’m not going to get that from Nancy Pelosi. Maybe it’s because I’m getting older, but people are being very nice. They too want to get it done.

Originally published in the Winter 2019 issue of ArtReview Asia

Annie Leibovitz. The Early Years, 1970 – 1983, Archive Project No. 1 and Wonderland is on view at Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong, 6 January – 12 February 2022