At some early juncture in the reading of this book – perhaps when its heroine sees ‘horses made of ice between the trees’ – you might like to check if you’re dreaming: welcome to the unaccountably strange life of Leonora Carrington. Painter, writer and subject of a spring retrospective at Tate Liverpool, she’s also one of the oddest figures to emerge from England in the last century. From her birth on a Lancashire country estate in 1917 to her death in Mexico 94 years later, she remained a magical, faintly disconcerting presence, defiantly attached to the weird familiars and phantoms of her imagination through spells of obscurity or madness.

As the contents of Carrington’s life can seem fantastical, Poniatowska knows that paradoxically the best method for accurately capturing its real texture is to transform it into a mysterious fable, a surrealist trick

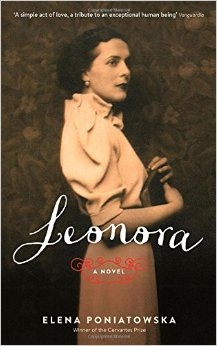

This book is a tender portrait that, according to its author, ‘has no pretensions whatsoever to being a biography’ yet supplies the most authoritative account of her life you can find. As the contents of Carrington’s life can seem fantastical, Poniatowska knows that paradoxically the best method for accurately capturing its real texture is to transform it into a mysterious fable, a surrealist trick first taught by André Breton’s Nadja (1928). Echoes of Carrington’s own books abound, too, hallucinatory memoirs full of wolf-headed women, drugged fudge and Gnostic prophecies that are seemingly intended for the oddest children imaginable.

In this more prosaic retelling, Poniatowska never responds to her subject with self-consciously freakish treatment or slack-jawed fascination, and even at its most outlandish, the story is luminously told.

An aristocratic changeling, Carrington first appears as a child roaming an empty landscape that forecasts the haunted terrain of her paintings. Ghostly boys cavort under the full moon, goblins sneak through her hair, and folklore, learnt in the lap of her beloved nurse, sets her mind ablaze. Soon she grows into a wildeyed debutante, rebuffing her father’s fortune so she can drift to Paris and fall under the spell of Surrealism.

Much of the book is dedicated to chronicling this supreme example of amour fou, powered by an electric sexual connection and an occult atmosphere

It remains wonderfully difficult to tire of tales about the Surrealists’s antics, and Poniatowska supplies them in a mad abundance that makes the clock melt: Luis Buñuel wonders aloud if there are any dwarves in Mexico – someone affirms their presence – Breton cuts an oracular dash through cosmopolitan Paris, acting with all the horny insouciance of a Greek god, while Picasso snakes around a party, that month’s lovestruck mademoiselle in tow, telling everyone that Antonin Artaud’s teeth have fallen out. Amidst the lunacy, Carrington falls head-overheels for Max Ernst, who appears as a character possessing all the sinister inscrutability of the birdmen that he compulsively drew and collaged. Following a delirious honeymoon phase where their involvement seems almost animal and imbued with mutual clairvoyance, all comes undone as various horrors strike. Ernst endures wartime internment and Carrington suffers her first psychotic collapse awaiting his return; and later, when they attempt to begin again, the intensity of their obsession has waned. Much of the book is dedicated to chronicling this supreme example of amour fou, powered by an electric sexual connection and an occult atmosphere, until Leonora delivers the immortal kiss-off, ‘I cannot live frozen in your shadow.’ Who do you think will play her in the movie?

She escapes the creepy domination games that trap other muses in the doll’s house of male desire, bolting for Mexico where she makes her greatest paintings. Poniatowska never attempts to puzzle out any pieces, favouring short phases of lyrical attentiveness to their peculiar climate.

Carrington’s work still supplies a cornucopia of untamable astonishments, going far beyond the textbook breed of Surrealism we’ve learned to understand with its schooling in psychoanalysis, Catholic mischief and the tricks of convulsive juxtaposition. Hers is a far more private art that wanders through Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510) into the darkness of Kabbalah and emerges in the looking-glass world of Lewis Carroll, all bound together with an air of gently unsettling innocence. Those hunting for explanations are in the wrong dream. But Poniatowska’s book assures us of how startling Carrington’s flesh-and-presence was, too, while drawing us back to the magnificence of an oeuvre so strange you can scarcely believe it was accommodated by the waking world. ‘I’m inventing all this,’ she once playfully claimed, ‘and it is about to disappear, but it does not.’

This article was first published in the April 2015 issue.