Photography, with its automatic claim to evidence what it pictures, emphasises that painting has never been suited to documentary, despite having been the default medium of visual record up until the end of the nineteenth century. Painting is only proof of its painter’s process. Contemporary painting that seeks to prioritise its documentary function is mostly either gauche or an ironic process of coming around to ‘realising that one can’t make an image’ of one’s subject, as Frank Auerbach once put it. It is either blinkered to a context that has overtaken it, or using its means to expose their limitations. Carol Rhodes’s paintings are of the latter sort, but surreptitiously so. Their topographical appearance proves to be a guise rather than a measure, as if abstraction had assumed the postures of realism to gain itself a credibility in which she doesn’t ultimately believe. These postures are not merely a set of received stylistic tics, but the deceptive signs of conforming to the powerfully empirical character of the British landscape painting tradition.

Born in 1959, and based in Glasgow, Rhodes makes relatively small oil paintings on gessoed panels, and rigorously linear pencil drawings on sheets of paper of approximately the same size as the boards. These are forms, formats and a subject that say something about the assumptions underlying them: that the world is amenable to naturalistic representation. Subject is as constant as scale and vantage: lightly built-up coastlines, extrasuburban conurbations and ‘light-industrial hinterlands’ – in Michael Hofmann’s phrase – viewed from what might be the altitude of a low-flying hot-air balloon, or a plane that has just taken off. Only in the occasional earlier work is a strip of sky visible above the table of land, and in the light of what was to come, it looks like succumbing to a convention of pictorial illusionism. Otherwise, resisting the illusionistic pull exacted by the familiar triad of sky/horizon/earth, the landscape fills the picture. This overallness is related to the essentialism of modernist abstraction – the synonymity it cultivated between composition and support – with the Earth as a metaphor for the picture plane. Even the conventionally lower vantages never quite seem to touch the ground. Rhodes’s paintings are consistently unpeopled, although dense with traces of habitation. Their elevated point of view is not naturally ours – at least only since the end of the nineteenth century, and then only by artificial means – as if the absence of the human referent required the corresponding absence of a human viewpoint to perceive it.

This sense of stoppage, of arrested motion, of frozen, abstract forms masquerading as elements within a scene testifying to human concourse, is a sign of the deceptiveness of Rhodes’s empirical rhetoric

The lack of human presence could be a function of distance, with the buildings just remote enough for their windows to be visible, but not the figures surrounding them. And yet it seems an ontological rather than merely perceptual parameter, and carries over to paintings that show their subjects at close enough range to reveal human activity. It is a question of divesting the landscapes of a familiar presence in order allow them to become repositories of states we project onto them: loneliness, disorientation, dislocation, the desire to escape. Distance from the action is as much a psychological condition as a matter of stand-point. Implicating the viewer (and artist), it is distance kept as much as distance from. But it is also another sign for the medium: for the relative reluctance of painting to let you into the image it offers. The landscape becomes subject rather than setting by avowing its condition as a taut conglomeration of painted forms, as painting before place. And the absence extends not only to that of people: the spaghetti junction of Rivers, Roads (2013) is devoid of vehicles, with no potential momentum to disturb its immaculate stasis; nothing threatening to interrupt the timelessness of the scene, no ulterior movement to compete with the measured drag of Rhodes’s brush, amplifying its smallest gesture against a static foil.

This sense of stoppage, of arrested motion, of frozen, abstract forms masquerading as elements within a scene testifying to human concourse, is a sign of the deceptiveness of Rhodes’s empirical rhetoric. After all, these are paintings that wear their Ruskinian badge of verisimilitude on their sleeve: from their Pre-Raphaelite-ish use of small, fine brushes on a smooth, white ground – cultivating the faint glow of the white’s luminosity – to the pert directionality of the strokes, sculpting blocky houses and regularly bulbous trees, or sweeping over the curve of the landscape, registering every nuance of its three-dimensionality. There are echoes of nineteenth-century plein air oil sketching, particularly the dour British variety, going back to the terse geometries of Thomas Jones’s late-eighteenth-century sketches from a Naples rooftop, marking the end of his European tour: a first and final foray into topographical naturalism for an artist trained in a classicism that stemmed from the artificiality of Claude Lorrain’s fecund Italian vistas, framed by glowing pines.

What makes these paintings’ details unsettling is their being plausible in themselves while straining credibility in their pictorial contexts

The plein air tradition of sketching in situ involved oil and water-colour painting on small boards and sheets of paper, executed within the landscape itself in order to capitalise on nature’s immediate presence to produce a more ‘truthful’ rendition of its effects, in contrast to an earlier, studio-based tradition, which manipulated generic coulisses and antique props into ideal arrangements. Ironically, Rhodes is adopting the tropes of one kind of painting to enact a process much closer, in its piecemeal arrangement of appropriated elements, to that of the art it was rejecting. She creates her compositions out of features she discovers in found photographic material – magazine pictures, aerial mapping – which are then adapted as she incorporates them into the network of a composition. Her marks claim to be in thrall to how things are, only to turn out to be referentless. They make us wonder what they might be trying to convince us of by assuming an air of what they are not; and then encourage us to double back and realise that perhaps this is what all representational painting does. Which, by extension, would make her style a metaphor for the workings of painterly illusion itself.

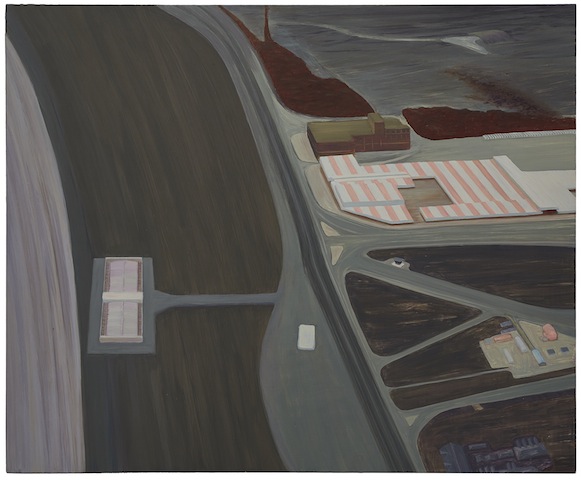

In this self-reflexivity, Rhodes is making postmodern paintings that resemble premodern paintings. ‘Network’ seems the right word because many of her compositions are elaborately structured by what seems like an excess of roadways; but also, more ironically, because Rhodes’s networks might be the antithesis of those that David Joselit had in mind when writing about contemporary painting’s theme of connectivity. They are axes of dissociation, networking to no purpose, in spaces in which no one is being connected. Exploring these silenced arteries, and the terrains they divide, one stumbles on minor glitches in the pictorial logic, like that odd, geometric edifice on a hilltop in Nicolas Poussin’s Landscape With A Man Killed By A Snake (c. 1648), which appears more like an Escher puzzle the longer you look at it. The Rhodes equivalent might be the roof of a hangar at the centre of Pier (Night) (2000), striped with a shocking-pink gaudiness that defies its air of terse functionality, and would hardly have been visible, it seems, in the limelight that presides over the rest of the picture.

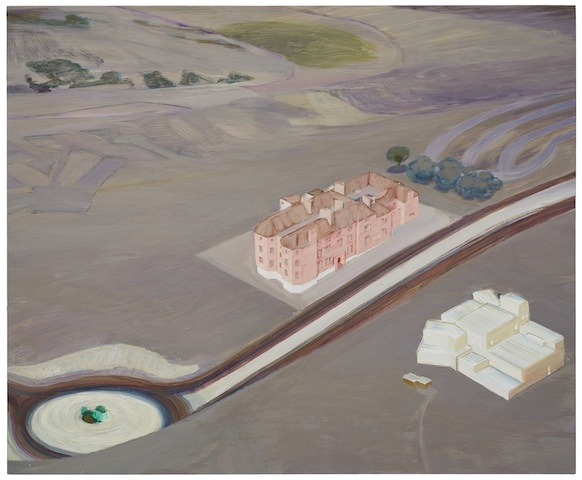

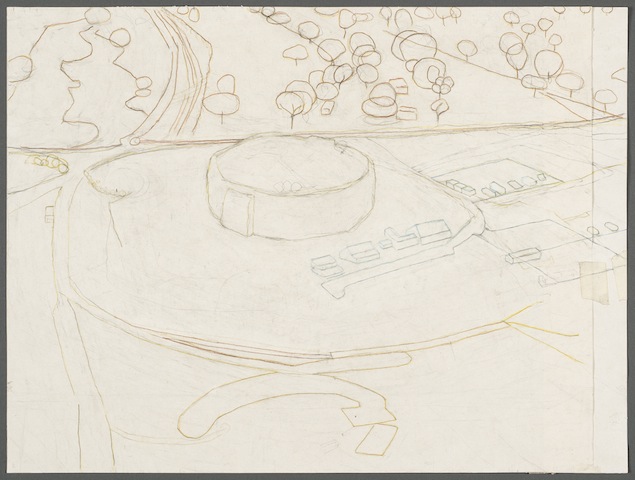

What makes these partially unassimilated details unsettling is their being plausible in themselves while straining credibility in their pictorial contexts. The early Road and Path (1997) – with its trees like flailing, underwater creatures, its dysfunctional vertical spikes blocking the entrance to a car park and its jarring architectural heterogeneity – is so blatantly a fantasy that it sacrifices the bedrock of realism on which Rhodes’s paintings usually depend and thrive. It is an attempt at a mode that might be called topographical surrealism, a brave oxymoron that doesn’t quite come off. In her mature work the fictiveness is covert or structural, a function of colour relations and the unlikely combination of forms that in themselves maintain an air of fierce objectivity. Two Buildings (2012) refers to an early-twentieth-century manor-style house and a brutally symmetrical industrial complex, facing one another across a roadway’s divide. Isolated on a barren plane, they seem to be expressing a mutual challenge. Their coexistence in this bleak environment seems less credible than their individual presences. The distinction is emphasised by the glow that seems to emanate from both buildings, jointly separating them from the dim space they occupy, as well as by Rhodes’s drawing of the same composition, which casts them as schematic shells, geometric figments of a design that has been constructed on paper out of a series of regular planes, rather than according to visual information gathered in the unpredictable perceptual conditions of a landscape lit only by dusk or dawn. This is painting that exploits the kind of disjunctions plein air naturalism was designed to overcome.

It is as if colour has broken loose of its realist base into a flight of free association

It is more by colour than design that Rhodes asserts the autonomy of her paintings from the documentary mode to which they seem beholden. Colour is transposed from a naturalistic register across the span of a composition until its relations make representational sense on their own terms, which may have only the most tenuous connection to how the place they picture might conceivably have appeared. The two patches of vegetation just off the coastal road of Pier (Night) look like huge, questing slugs because their reddish-brown colour fails to be taken up by the greyish setting. It is as if colour has broken loose of its realist base into a flight of free association. Business Park (Night) (2007) is a dark painting; its turquoises, viridians and crimsons as precisely coordinated as they are apocryphal, like an infrared intensification of the darkness’s voiding of colour, an effect that does not seem arbitrarily subjective, but calibrated across its spectrum into a matter-of-fact light specific to a fiction, invented rather than reported, but still able to trade on the accuracy of its report.

But Rhodes’s art would be didactic or academic if her pseudo-realism were merely a type of formalism – a means of arriving at colour schemes that remain in the subjunctive: as if a landscape looked like this – and not a way of positing places specific to a particular world to which they might all belong, and which each painting extends in its scope. The characteristically furtive, clandestine air of the buildings she paints – as if they were concealing sinister secrets – is a function of their seeming to have been designed first and foremost in the abstract, out of geometric shape and colour, and only secondarily with the intention of creating a realistic image of architecture. A focus on form manifests itself as an aspect of the charged atmosphere of the world into which her art projects us.

Rhodes’s landscapes are unlocatable because they are fantastical – they do not exist outside of a painting’s fiction – and because they are remote.

It is a clue to how that world might be defined, and what it might signify, when she writes that she is painting ‘left-over land’. Her paintings crystallise the feeling of passing through, or over, a dark, foreign landscape, only able to make out the vague lineaments of obscure industrial features and isolated housing; a feeling of uncertainty that the remote detail will continue to exist outside of the accident by which it is perceived. Rhodes’s landscapes are unlocatable because they are fantastical – they do not exist outside of a painting’s fiction – and because they are remote. They are both far-off and farfetched. They are ‘nowhere places’ both in the sense of their fictiveness and their obscurity, their being nowhere to be found and ‘in the middle of nowhere’, the former a metaphor for the latter, and vice versa. This double-edged obscurity, as the focus of an eminently representational idiom, is a manifestation of the most eerie kind of science fiction: that which is not made safe by being placed under the remit of the familiar unknownness of outer space or the distant future, but shares the ground under our feet.

The obscurity of the unperceived, or seldom perceived, may also imply the marginality of painting as a medium for documenting reality in our photography-oriented image world; but also that what painting is able to show us may be an alternative reality to the evidenced but not experienced digital image, reversing those terms. It is among the paradoxes of Rhodes’s painting that her protracted process of arriving at a painting’s colours and forms doubles as a means of conveying to the viewer an experience of a place that its image informs us is distinguished by human absence. In the era of Google Earth, in which we assume that everything is either visible or can be made visible at the touch of a screen or click of a mouse, Rhodes pictures places beyond our means of establishing their existence, inaccessible except imaginatively. This makes her art a parable of the limits of information, meticulously striving to inventory spaces that by definition cannot be verified.

This article with appeared in the December 2017 issue of ArtReview