There is a lucid, analytically trenchant text by Ajay Kurian, ‘The Ballet of White Victimhood’, about Jordan Wolfson’s Colored sculpture (2016), written with the anger of desperation. Kurian, an American of Indian origin, wrote it a few days after Trump was elected, looking for explanations in his colleague’s work for the victory of the self-proclaimed silent majority, ‘a breed of white males who believe they are persecuted while being the aggressor, and are powerful while maintaining a sense of painful fragility’. It is precisely this cognitive dissonance that Kurian continues to explore in his undoubtedly ambitious Düsseldorf exhibition American Artist.

On the upper floor of the completely darkened gallery, a deep flokati rug in muted cream colour is laid out, conjuring the atmosphere of a filthy motel. Old pizza boxes are scattered about (Locavores Eat Globally, all works 2017), next to an overturned fridge full of broken salsa bottles, exuding an acrid stench (Master Slave Complex [Proleptically Speaking], II). The sauces are labelled with slogans such as ‘Trump that Bitch’ and ‘Redneck Sauce’, suggesting the following interpretation: this is the parallel world of one of those hate-filled white men who believe in the ‘Pizzagate conspiracy’ and detest immigrants, but still eat Mexican sauces, because eating soy sauce makes you gay; due to the oestrogen, of course! Yet the brand of the fridge – Privilege – indicates that this supposed war of cultures boils down to the fear of losing one’s privileges. Even though the works are quickly decoded, the immersive environment very convincingly breeds unease. Kurian’s case for necessary intervention is also persuasive, although one may be tempted to ask if he himself is not using the same divisive us/them rhetoric in reverse.

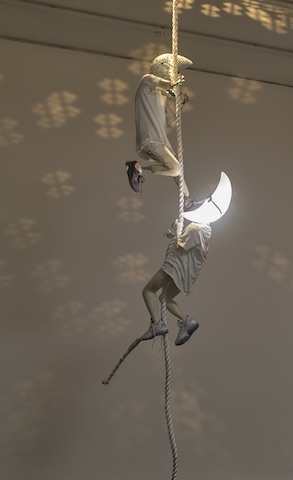

The installation Satters and Pullman, previously shown at the last Whitney Biennial, is significantly more complex. Accompanied by Bobby Darin crooning Mack the Knife (1959), two figures hang from a rope, the upper kicking the lower in the face. The figures’ faces are made of sunglasses-wearing crescent moons, inspired by an old McDonald’s advertising character called Mac Tonight, which, like Pepe the Frog, is very popular in alt-right memes on 4Chan and 8Chan. Again one is confronted with the coarse social Darwinism of the American right, which here also turns inward, since one Mac Tonight is beating up another. Via the music, Kurian interlaces the whole thing with the chequered history of the ‘murder ballad’ Mack the Knife from Bertolt Brecht’s 1928 Threepenny Opera (incidentally also the song in the ad featuring Mac Tonight), which over the years has turned the criminal into a hero.

Since the financial crash of 2008, the call for partisanship and political intervention has grown louder, especially in the artworld. Kurian has taken up this call after previously making eclectic material composites that suggested he was turning into a contemporary revenant of Jason Rhoades. This is to be welcomed; the only question is whether his rhetoric is sometimes not too explicit, a rebuke frequently and rightfully levelled at political art in particular. I’m thinking of the completely black room in which a white vulture (Untitled, 2017) glances observingly at a light sculpture (Locked, 2017) recessed into the wall, which turns out to be a dying sun. Dimly lit, positioned on a red-veined travertine pedestal and fabricated using pricey Carrara marble, the vulture strongly recalls an eagle and thus the heraldic animal of the US president. Not very subtle, though the staging of this end-times scenario is once again stunning.

How Kurian uses darkness, colourful light sources and dim lighting in this show to trigger bodily unease and defensive reflexes is particularly impressive. Intended or not, the relationship with the works is thus dominated by sentiment, precluding any rational access, which in turn suggests the absurd way Trump supporters deal with facts. In any case, Kurian’s ‘Murder Ballad for America in Sculptural Form’, as the press release has it, caters to an illusionism based on empathy, which Brecht had already rejected for any politically progressive art – yet his most famous counterexample, of all things, is The Threepenny Opera.

Ajay Kurian: American Artist at Sies & Höke, Düsseldorf, 17 November 2017 – 13 January 2018

From the March 2018 issue of ArtReview