By the time I left this enormous, double-venue exhibition featuring over 150 works, I no longer had the faintest clue as to what ‘Minimalism’ means. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Art can be at its most powerful when it unsettles rather than affirms. Particularly in the context of the current fetish for retelling art’s histories and reexamining old tales from different points of view, a trend of which this – billed as the first survey of minimalist art to be staged in Southeast Asia, and the first exhibition on the subject to incorporate art from the region under the Minimalism brand – is self-consciously a part.

The exhibition at the National Gallery (where around 120 works are housed) begins traditionally enough, with some of the precursors to the heyday of New York Minimalism during the 1960s, albeit paintings (variations on the theme of black, largely from the late 1950s) by Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko and Frank Stella are grouped together in the opening corridor of the show in such a cramped way that the ultimate sensation is that the curators simply wanted to dispense with art-historical givens as quickly as possible. Further in we come across works by the stars of the gang – Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt and Robert Morris – but by then the territory has been expanded, both geographically and temporally. We start to encounter works by Tang Da Wu, Lee Seung-taek, Lee Ufan (and a section on Mono-ha), Roberto Chabet, Rasheed Araeen, Ai Weiwei, Anish Kapoor, Richard Long, Mona Hatoum and Olafur Eliasson. Some, such as three works from Haegue Yang’s Sol LeWitt Upside Down series (2017), made up of white, mass-produced Venetian blinds and riffing off LeWitt’s concerns with linearity, seriality and modularity, make self-conscious reference to precedents from the Western canon. (Although the fact that the South Korean’s works are supported by walls or ceilings, rather than freestanding as are LeWitt’s structures, and hung upside down might be seen as an oblique insistence on some form of contextual difference.) Others, such as self-taught Myanmar artist Po Po’s Red Cube (1986), come from somewhere else altogether.

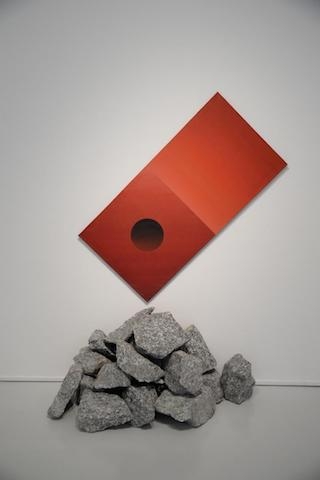

The work comprises a red oil painting that might, given its tonal variations, suggest two faces of a cube, the one face with a hole in it, hung at an angle above a pile of gneiss rocks. It’s informed by an interest in subverting the traditional viewing of paintings as portrait or landscape as well as Zen and Theravada Buddhism (Buddhist monks are known to retire to the jungle and build stone pagodas to focus the attention). In the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition, the artist asserts that he had never even heard of Minimalism when he created the work (until late 1988 the country was relatively isolated). At moments like this (and there are several), you wonder whether the New York version of Minimalism needed to be addressed at all. But other works in the exhibition build on and complicate such ambiguities.

A selection from Simryn Gill’s photographic series My Own Private Angkor (2007–09) documents a compound of abandoned houses, built during the 1980s, in Port Dickson on Malaysia’s west coast. Each image features rectangular panes of glass, bright when the sun shines on or through them, dark when it does not, that have been removed from their window settings so that they could be stripped of their valuable aluminium frames. Apparently without value, they are carefully rested against walls or balconies. To a degree, the panes of glass and their bare architectural setting offer a formal echo of the opening hang of Newmans and Reinhardts, but the situation Gill documents is found, rather than constructed (albeit the photographs are), and speaks to the passage of time, economics, recycling and ruination in an equatorial context: the kind of factors that Minimalism of the hardcore 1960s variety would see as external to the artwork. While the exhibition might be arguing for Minimalism as a global movement, Gill’s work insists that regional specificity has a role to play. If New York Minimalism was about pulling down the blinds on anything external to the work of art, this kind of Minimalism is open to the world.

Within the context of both parts of the exhibition, but in the display in the ArtScience museum in particular, that notion is further pursued by the staging of Minimalism as something grounded in Asian spirituality and religion. The Rig Veda is quoted in wall texts, the teachings of the Buddha more openly evoked. Again, the fact that such philosophies have a much deeper history than Minimalism itself somewhat begs the question of why Minimalism (rather than, say, Asian mysticism, which also had an influence on many minimalists in the US and Europe) provides the framework for the show. More successful is a direct attempt to document the historic contribution of women artists (among them Simone Forti, Mary Miss, Carmen Herrera) into the expanded narrative of what is largely a male preserve. As is an expansive mini-exhibition of soundworks: an important reminder that Minimalism, as displayed here, was operative across disciplines (dance and performance are included in the National Gallery) as well as across time and space.

There’s a sense, given the expanded chronology, geography and substance of the works in both institutions, that this show fits into a wider theme of destabilising the past (in terms of its accepted narratives and geography) in order better to understand our unstable present. On the other hand, its sheer inclusivity can at times mean that Minimalism seems to mean nothing because it seems to mean everything. To the extent that you wonder if all this ‘blockbuster exhibition’ really demonstrates is Minimalism’s brand value. No more so than in an iteration of Martin Creed’s Work no. 1343 (2012) installed in the National Gallery café. The work incorporates a mishmash of furniture, utensils and receptacles (‘visitors are invited to contribute their own wares to the artwork as long as they are in good condition’) within the framework of the existing refectory. On the menu: a Pu’er Mousse Cake inspired by Ai Wei Wei’s Ton of Tea (2008) and the Infinity Drink – ‘an invigorating blend of ginger flower, lemon, mint and soda’.

Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. at National Gallery Singapore, ArtScience Museum Singapore, through 14 April

From the March 2019 issue of ArtReview