Just a few years ago, it was possible to believe that Brazil had shaken off its turbulent history. The country had seemingly emerged into the clear waters of a globalised world, and many thought that it would swim forward from there: with regular elections, moderate social justice improvements and an embrace of the free market. Of course, this didn’t work out. Like a monster from the depths, Brazil’s past has resurfaced. The country is now run by former vice president Michel Temer, who rose to power by turning on President Dilma Rousseff, a onetime leftist guerrilla, and betraying their joint campaign promises, creating an unfathomably unpopular, conservative crony-capitalist government in the wake of her impeachment. This October, the country may well elect a hard-right apologist for the 1964–85 dictatorship, with a running mate who has said the country inherited its “laziness” from indigenous Brazilians and its “criminality” from the blacks. For most of the twenty-first century such a statement from a major candidate would have been unthinkable. But if we step back and take a look at Brazil’s history, we’re quickly reminded that they are the attitudes that have been held by most of the men that have run the place for five centuries.

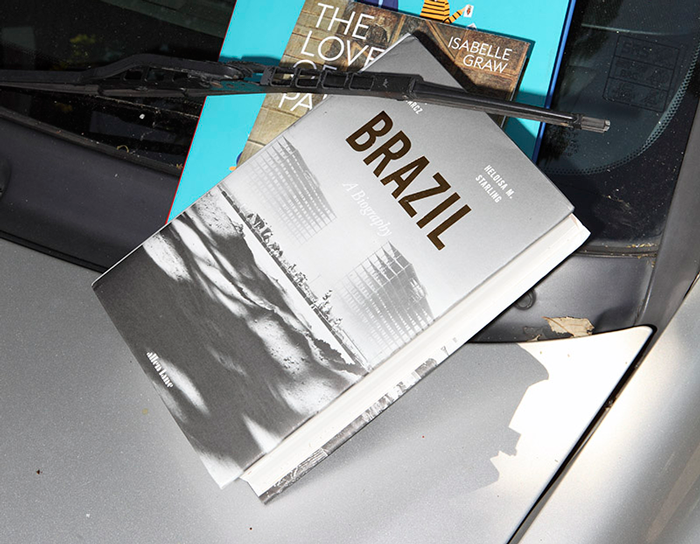

This seems a good time to take stock then, and the translation of Lilia Schwarcz and Heloisa Starling’s Brazil: A Biography offers English language readers an opportunity to learn about the history of the country from its ‘discovery’ and the complex interactions between European explorers and cannibal natives, to its colonial role as brutal supplier for the world’s sugar addiction, a Wild West of gold mining and regional rebellions, through the strange period of empire (with king, court and all) in the New World and into the modern era of populist dictatorship, democracy, murderous military dictatorship and wobbly transition back to democracy. This is an imperfect but breezy translation of the bestselling 2015 original, which came out as Brazil was in freefall but had yet to hit the rock bottom of Dilma’s impeachment. The authors pay particular attention to the institution of slavery and the violence it relied upon; to political leaderships frequently characterised by backroom negotiations among friends and family; and to intermittent explosions of popular discontent – all legacies that have recently reemerged. They also pay due attention to the crucial role that diverse aesthetic movements played in Brazil’s struggles, from indigenous-exalting Romanticism, apolitical bossa nova, the Tropicália new left and the explosion of revolutionary rap.

This is an 800-page book written by Brazilians for Brazilians, but its consequent areas of focus can be doubly revealing, rather than alienating, for Brazil-curious foreign readers as the authors address various misconceptions widely held among their compatriots. They dispel the myths that slavery in Portuguese America, though more widespread, was somehow less cruel than in North America – the stomach-turning description of ‘iron masks that prevented the slaves from eating earth as a way of provoking a slow and painful death’, the earth-eating a method of suicide, is enough to convince otherwise – and that Princess Isabel somehow benevolently granted abolition to the country, when it was the consequence of bottom-up agitation, international pressure and heroic slave rebellion.

Their deeply Brazilian approach is also reflected in a tendency – common to most countries this large – to downplay the influence of the outside world. The country’s successes or failures are attributed to Brazilian decisions and their ethics, or lack thereof. This is not incorrect – it is true that the murderous military dictatorship was Brazilian-built – but it is one-sided. That similar regimes popped up all over South America at the same time was due to larger Cold War forces, not because everyone happened to make the same mistakes.

But perhaps an emphasis on personal morality and historical contingency is the best way to confront Brazil’s past, identifying its monstrous side as well as the opportunities the past opens. As the impeachment of Rousseff proceeded over the past two years, educated Brazilians, shocked by the snowballing support for another military coup, often relied on variations of a slogan – on the street and in heated online arguments – aimed at those who didn’t know what the horrors of the previous regime entailed. “Vai ler um livro de história!” – go read a history book.

Brazil: A Biography, by Lilia M. Schwarcz and Heloisa M. Starling, Allen Lane, £30 (hardcover)