That there is a degree of censorship (or a pressure not to show politically critical works) in the public art institutions of many Asian countries is no secret. Neither is this state of affairs only prevalent in developing countries whose systems of government fall short of democracy. In South Korea, a country that achieved enduring democracy about 25 years ago, following revolts against dictatorship and authoritarian regimes on several occasions in the latter part of the twentieth century (the April Revolution in 1960, the 1980 Gwangju Uprising and the June Democratic Uprising in 1987, to name a few), strong and irrational pressure is now brought to bear on the country’s museums and public institutions.

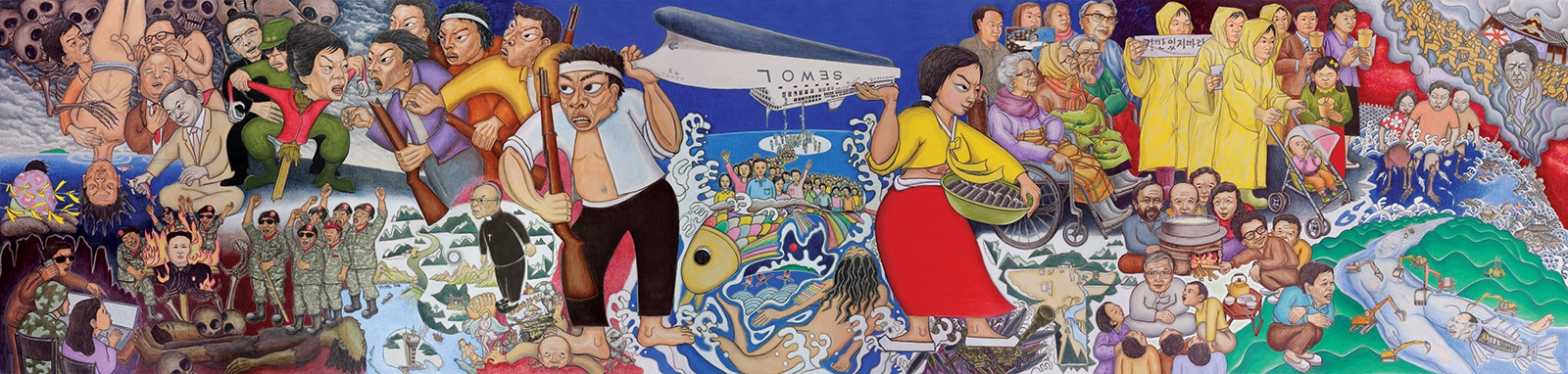

During the autumn of 2014, following the April sinking of the Sewol ferry, Hong Sung-Dam, who had been a prominent member of the Minjung art movement during the 1980s, turned in a painting satirising the current president for an exhibition commemorating the 20th anniversary of Gwangju Biennale. Subsequently, the Biennale Foundation decided not to show the work, and both the curator in charge of the exhibition and the Biennale Foundation president, Lee Yong-woo, resigned. (In fact, there was another controversy around Hong Sung-Dam’s painting: politically radical artists and curators had hesitated to support him because they found it hard to defend his aesthetics and didactics. Yet when we hesitate to defend such obvious cases of censorship, it becomes harder to defend ourselves in more complicated circumstances.) In the past couple of years, cases of direct censorship or pressures of indirect censorship have drastically increased in Korea’s art and culture sectors. But an even greater problem is that recent cases of censorship have evolved to take on a preventive form, perhaps because the direct censorship of an artwork is more easily picked up by the media and the public, thus putting more strain on bureaucrats.

Last autumn it was revealed that a blacklist of artists, directors and writers who incorporate elements of, or metaphors for, a political agenda had been handed to the juries selecting candidates for funding in the theatre and literature sectors

Over the past several years the means of censorship of artworks have, broadly speaking, taken three forms: 1) direct censorship of the artwork, 2) sponsorship and funding, and 3) personnel. While the first case is a post-event procedure carried out normally by a conservative government or the bureaucrats governing public institutions in which the grounds for censorship are laid out clearly, the second and third cases are preventive, designed to eradicate controversial elements in advance of any ‘selection’ process. After the incident of censorship in Gwangju, the ‘preventive’ measures within art and culture funding organisations with a very strong affiliation with the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (MCST), including Arts Council Korea (ARKO), have come under increasing scrutiny. Last autumn it was revealed, following widespread media coverage and a National Assembly inspection of ARKO, that a blacklist of artists, directors and writers who incorporate elements of, or metaphors for, a political agenda had been handed to the juries for selecting candidates for funding in the theatre and literature sectors. While the case of Hong Sung-Dam was an obvious instance of censorship, the blacklisting reveals that in reality the situation is even more critical.

And the problem reaches yet another level when people decline to resist such pressures. The truth is that there are more curators and artists who make compromises or ‘practical’ decisions in the face of censorship and in full awareness of their colleagues’ difficult situations – which include recent cases of hardship, bullying, exclusion and even dismissal – than there are those who express solidarity with them. All of which gives more space for bureaucrats to see artists and curators as people who can be managed, ruled and tamed.

Last November, at the annual conference of the International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art (CIMAM), held in Tokyo, three board members (Van Abbemuseum director Charles Esche; SALT director of exhibitions and programs Vasif Kortun; and Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art director Abdellah Karroum) resigned from the board, pointing out the inadequacies of CIMAM’s current president, Bartomeu Marí. In March, Marí had cancelled the exhibition The Beast and the Sovereign at the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA, of which he was then the director), having deemed Austrian artist Ines Doujak’s work, which ridiculed former Spanish king Juan Carlos I, obscene. Following a worldwide controversy, he reopened the show and resigned from his post. This is what the three board members had to say: ‘We believe CIMAM’s main task today is to defend as much as is possible this space for debate and to set ethical standards of behaviour towards artists, curators and the public. The recent course of events at MACBA and within the board at CIMAM have led us to doubt whether our current president can defend those values credibly. We therefore feel we have no option but to resign from the board as we no longer have confidence in how it represents the interests of CIMAM members.’

This happened right around the time when the news of Marí’s strong candidacy as director of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) in Seoul started to circulate. Artists and professionals in the field had issued a statement under the name of ‘Petition4Art’, expressing opposition to the appointment procedure and demanding that the MCST investigate the censorship controversy of its strongest candidate before going ahead with the appointment. The petition, which launched last November, garnered a total of 830 signatures; a second, started after Marí was appointed director, gained 550 (myself among the signees of both). Parallel to the petitions, individual artists organised an open forum, a series of one-man protests and a ‘poster relay’ (in which artists and designers collaborated on creating a series of protest posters), all of which drew a kind of attention to Korea’s normally reserved art scene that had not been present since the 1980s. As much as anything, this was surely a strong response to an accumulation of censorship issues and a communal objection to a bureaucracy that has managed and ruled, according to its own agendas, the field.

The issue has also become a hot potato because the government’s operation of indirect censorship has been closely coupled with its management of major appointments in the art and culture fields. In mid-February, Yong-kwan Lee, director of the internationally acclaimed Busan International Film Festival (BIFF), was finally fired by Busan’s centre-right mayor after the BIFF team had rejected any censorship of screenings of Diving Bell: The Truth Shall Not Sink with Sewol (2014), a documentary film investigating the Korean government’s dysfunctional rescue attempts in the wake of a ferry disaster in which over 300 people died. Lee was under heavy pressure to resign his position for a year before this dismissal, and his team faced prosecution on charges brought by Busan’s party.

Recent appointments in other branches of visual art had also featured pro-government figures. Of course, Marí has worked for the past decades in the international art scene and is far from a conservative character. However, there were dubious points in the censorship controversy and the appointment process that resonate with other nominations of MCST figures. Out of ten or so applicants from the first round, Marí advanced to the second round alongside two relatively weak Korean candidates, and he was the only foreign candidate who went on to the final interview, despite the government’s full knowledge of his censorship issues. While there have been some artists from the older generation who expressed discontent at the prospect of a foreign director for the national museum, the majority consider the Korean art scene part of an international field. Suspicions have been further fuelled, however, by the revelation of a modification to the museum’s regulations, which now require MCST’s consent in a number of sectors that used to be the director’s domain.

MCST did not respond to Petition4Art’s request for clarification on this point, but Marí sent an email in mid-November to explain it himself. Among the many points he offered in his defence, I found one especially perplexing: he argued that what had happened at MACBA had not been a case of censorship but of ‘a decision to protect the institution as a director’. Yet his explanation of the complicated local politics of Catalonia and the political tensions between the central and local governments sounds very familiar in the context of Seoul’s public institutions, which face a catch-22 situation between a conservative rightist central government and Seoul’s leftist local government. Over the past year, SeMA, the city museum in Seoul, has also suffered controversial cases of interference, modification or even withdrawal of work prior to exhibition openings. What we understood was that such cases mostly had occurred in order to avoid any kind of noise or bad attention to the city, as well as to protect the mayor’s next election run.

Is it possible that the protection of the institution takes place without the close collaboration of governments or any power in politically precarious societies? What does the notion of the protection of the institution mean in a country or region where censorship is commonplace? Where does this kind of cooperation eventually end up? And does this way of protecting an institution help to sustain and develop a long-term artistic vision? Isn’t it nothing more than professional self-preservation?

Unfortunately, as a result of the gap between current artistic practice and most Korean public institutions, many Korean artists do not consider such institutions as guardians of the art scene. There have only been a few cases over the past ten years or so in which field-friendly curators were appointed to direct such institutions, and when such cases did occur, the directors were mostly shunned, interrupted or even punished by bureaucrats. In our local context, an institution never gets ruined, and it never protects the vigorous artistic present in the sense of protecting the institution.

But history does strive from time to time to remember those who have resisted. Bartomeu Marí also promised at the inauguration of his directorship to play an original and responsible role in the Korean art scene, emphasising that he won’t help any censorship, and I believe that his words and commitment will help him work with the local art community during his tenure. Considering the individuality and incompatibility of perspectives among different groups and generations, the unprecedented solidarity of more than 830 petitioners is, to say the least, significant to the scene. At the time of writing, Petition4Art is preparing a symposium scheduled for mid-March, as its final stage of activity.

This article first appeared in ArtReview Asia vol 4, no 2.