Mark Rappolt meditates on luxury development, negative space and resistance, while watching a new videowork by WangShui

Bel-Air is a luxury residential complex located in Hong Kong’s Southern District, next to the Cyberport business development and between the Peak and the South China Sea. Phase one of the project opened in 2004, with a total of 527 residential units distributed across seven blocks so that there are no more than two or three apartments per floor. ‘They mostly have open sea views and balconies,’ boasts the estate agent’s brochure. ‘They all have light wood finishing and luxury fitted kitchens and bathrooms.’ The eight core blocks that make up phase six were designed by Foster + Partners and completed in 2008. They are paired to give the appearance of four massive structures forming a wave. ‘The design concept draws on both a combination of European precedents – the Royal Crescent in Bath and the urban edge of the French Riviera – and Hong Kong’s contemporary vernacular of breathtaking vertical living,’ the practice says, giving precisely the vision of history, royalty, pleasure and innovation that is the stuff of every developer’s dreams.

Prices per unit have more than doubled since the development opened, even factoring in a decline in property prices caused by the economic crisis that has followed the COVID-19 pandemic. According to The Standard (‘Hong Kong’s biggest circulation English daily newspaper’), Xu Chenggang, an economist and honorary professor at the University of Hong Kong, ‘sold a 1,126-square-foot unit at Bel-Air in Telegraph Bay for HK$30 million’ earlier this year, having bought the unit for HK$13.8 million in 2009. But you’re not reading this article for advice on the property market. At least I hope not.

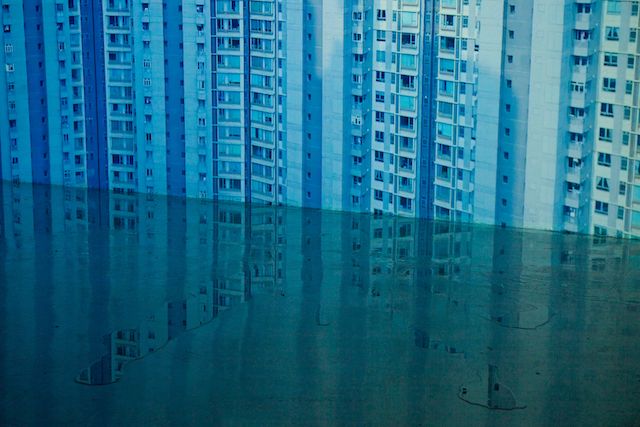

Bel-Air is the subject of From Its Mouth Came a River of High End Residential Appliances (2018), a videowork by WangShui that was first shown as part of a solo exhibition at Triple Canopy in New York and subsequently as part of the group exhibition Holy Mosses at Blindspot Gallery in Hong Kong at the end of last year. Although, as the video progresses, it becomes clear that emptiness, rather than Bel-Air, is the real subject of From Its Mouth… Unless it’s feng shui, Chinese mythology or WangShui themselves. Perhaps clarity is not the point. Perhaps the point lies in the fact that everything this work appears to reveal it immediately conceals.

Take the Bel-Air apartment blocks. They are in shot for almost every second of the video, but they remain nothing more than blank facades, mute objects animated only by the voice of the narrator purporting to speak for the artist themselves. “A wall,” is how the male narrator describes Bel-Air at one point.

Or take that artist. At the beginning of the video, the narrator (who delivers his lines in a lethargic, monotonous monotone) informs us that if we look to the lower left of the screen, we can see them and their drone-operating cameraman, Hercules, just as they disappear out of shot. Even if you do notice them, they are far below the camera. Tiny as ants.

While the name ‘Bel-Air’ is presumably intended to trigger Fresh Prince-type associations with the West Coast of the US, it is in fact fresh air that contributes the most striking aspect of the blocks’ architecture. Each of them incorporates a ‘dragon gate’ – an empty space between three and four storeys high at the rough centre of these 50-storey blocks – which, according to feng shui, allows dragons to fly through this architectural fortress (the community is gated) from the mountains of the Peak in order to drink from the South China Sea. Thus the qi flows through Bel-Air. Although such an ostentatious waste of valuable space is something, the narrator suggests, that only adds to the feeling of wealth and luxury of the development itself. (Cynics would add that the gates placate locals with obstructed views, that they make alien structures seem local or that they allow adequate ventilation while maximising unit space.) WangShui’s project, we are told, is to chase the dragon: to fly a drone camera through these gates in order to replicate the mythical creature’s journey. Although, when Hercules asks why exactly they want to do this, WangShui rather cryptically reports, “I explained to him that it was the only way that I could become who I wanted to be”.

Feng shui was designated a ‘feudalistic superstitious practice’ and banned in China when the CPC came to power in 1949. At the dawn of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) it was included among the ‘four olds’ (old ideas, old culture, old customs and old habits) that the revolution sought to eradicate. And while feng shui has experienced something of a revival in China over recent decades, it remains illegal in the PRC to register feng shui consultation as a business or to advertise feng shui services. Consequently, the narrator informs us, its enduring influence in Hong Kong and on Hong Kong’s architecture represents a form of resistance to all that, just as much as it represents a resistance to Western rationalism (for which we might read capitalism). And in this sense the dragon gates represent carefully preserved voids amid competing ideologies. And a shock of the old; lacunae in time as much as space.

Meanwhile, the narrator informs us, WangShui has been filming Hercules on their iPhone as he operates the drone controls. He taught most of the drone operators in Hong Kong and has a unique two-fingered way of operating the joysticks. We get to see none of that. The drone continues to approach Bel-Air and its dragon gates. Eyes without a face.

Art, we are always told, is about invention. As we fly towards the hole, the narrator tells us about how, according to Chinese legend, each emperor would customise a dragon to fly them into the afterlife. And pursue that dragon through their lives. These dragons were fantastical chimerical creatures made up of bits and bobs of other animals – a being made up of the things we do know to describe something we don’t. In The Classic of Mountains and Seas, a compendium of 204 descriptions of mythological beings (which the narrator now channels) dating, perhaps, from as early as the fourth century BCE, the Torch Dragon has a human face and a snake’s body, and he is scarlet in colour. Which is a little like the Aide Willow, except that the latter has nine heads and his snake-body is green. Meanwhile Mount Drum sports a human head on a dragon’s body; except when he turns into a hill peasant, when he looks like a kite, with scarlet feet and a straight beak, yellow markings and a white head. The Big Bee looks like a locust and the Crimson Moth looks like a moth. Well, you get the picture. Even if there are no pictures of such beings in WangShui’s video. Just the assertion that they are interspecies and the words coming out of the narrator’s mouth. And an image of apartment blocks punctured by holes.

Now WangShui chases the dragon. “The dragon I have in mind doesn’t have a singular body,” the narrator states. “It shifts between endless vantage points aggregating an infinite live image of me. Its name is WangShui. If the camera is the body and the lens the skin, it becomes almost entirely undetectable as it mirrors its surroundings while recording.” Just a wall of apartments punctured by holes. “I don’t want to know what it is. I don’t want to know what I am. Or where I am. Or whether or not this is cinema,” the narrator drones.

“Call me an orientalist. A hyperorientalist Chinese American raised in East Asia but not China, who has made it their life’s goal to lose all cultural traction but ended up making work about being Asian anyway, because the personal seems more political than ever,” the narrator says, the tone of their voice becoming a little more excited, the pace faster. “Clock me as a gay Asian bottom,” they continue. “Even though I haven’t had anal sex in years. Because I refuse to accept that my physical body must dictate how I have sex or who I have sex with… or that I should trust my highly suspect sexual desires that still propagate a Eurocentric hierarchy of desire… even though… I don’t want to be male anyway.” We never see the drone completely penetrate the gates and come out on the other side (although with the first gate it is almost all the way). It might have done when we weren’t looking or in a section that WangShui cut. By the end of the 13-minute video, which cuts between approaches to various of the gates, it’s hard to work out which side we’re looking at anyway.

All images courtesy the artist and Blindspot Gallery, Hong Kong

From the Spring 2020 issue of ArtReview Asia