The Historian’s Eye consists of black-and-white photographs taken by writer and historian William Dalrymple using his mobile phone, edited through the Snapseed app and then printed in archival pigment. The images are not unlike those on Dalrymple’s Instagram account: the contrast is turned all the way up, and everything is kept stormy and dark.

The photographs were taken between 2015 and 2017 while Dalrymple was researching his forthcoming book The Anarchy, for which he has travelled through India and Pakistan. He visited pleasure grounds, battlefields, old Mughal havelis, palaces, forts, mosques, Sufi shrines, temples, old colonial townhouses and barrack blocks. The wall text is explicit about the use of a Samsung Edge phone, the purchase of which ‘led to the rediscovery’ of Dalrymple’s ‘first love’ – photography. The text also notes that the photographs are intended to ‘trigger fictitious memories of an older, different, more elegant world’. Dalrymple indulges some family history to occasion this more elegant world: Immersing the Goddess, Durga Puja at Prinsep Ghat, Calcutta (all works undated) shows an effigy of the goddess Durga being taken into the waters at Prinsep Ghat, which is named after Dalrymple’s great-uncle James Prinsep, whose Wikipedia entry describes him as an ‘orientalist and antiquary’, ‘best remembered for deciphering the Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts of ancient India’.

Dalrymple, for most of his career, has continued this tradition of ‘deciphering’. His particular interest is the Mughal Empire, which is the subject of most of his research and several books, and for which he has travelled extensively. To put it bluntly, Dalrymple’s whiteness, colonial affiliations and Oxbridge roots have offered him unfettered access to the subcontinent, so much so that in 2013, he was invited to the White House to advise an AfPak (Afghanistan–Pakistan) strategy team. He is also founder of the Jaipur Literature Festival, a yearly affair that continues, with each iteration, to tighten its links to India’s current rightwing Hindutva leadership, and which marshals the borders of the Indian literary scene.

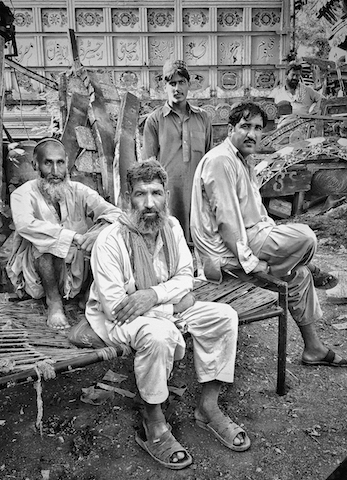

There is no doubt that Dalrymple is an influential man, and part of the lure of his photographs is that they provide a glimpse into his physical proximity to a history that most of us in the subcontinent would find difficult to reach, as travel between the divided nations has never been easy. Some of Dalrymple’s photographs take us to Gilgit, a Pakistan-administered territory that has often come into dispute over India’s claim to it (in 1947, its maharaja had signed an instrument of accession joining India against the wishes of the population, leading to a mutiny and eventual accession to Pakistan); to Chitral, a town nestled in the Hindu Kush mountains, a favourite among the Pakistani elite; and to Abbottabad, where US Navy Seals led the assassination of Osama Bin Laden in his family compound and hideout. Dalrymple befriended truck painters near the Pakistani Military Academy in Abbottabad, and photographed the group portrait The Truck Painters of Abbottabad, Pakistan. Of the photographs in the series, it is the portraits that work best, formally, as there is a cinematic quality to the light that admits to their fiction, and to the fictionalising predilection of their maker.

Dalrymple likened himself to French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson in a recent interview with The Sunday Guardian: ‘If Cartier-Bresson were alive today, I feel he would definitely be using a cellphone camera. It allows for that sensation of being the hunter, walking on tiptoe through the forest, camouflaged. It is, in a sense, guerrilla photography.’ This is an uncomfortable premise, and there is something about the photographs that makes them difficult to trust. The contrast is too overblown, and the light inconsistent and confusing to the eye. But this is not the issue here. The photographs have been enlarged beyond what their pixels can hold, and each appears grainy: a poor print. Neither is this the issue. These are the most interesting details of the photographs – they speak to their medium and introduce a conversation about how we bring expectations about what an image should look like into the white cube. But this is not a conversation Dalrymple is seen to have; in fact, there is no critical inflection to the show. Instead, the work is intentionally nostalgic and wistful, offering little nuance. Landscapes are made inanimate and abject, and public spaces (such as mosques, forts and temples), which are otherwise bursting with people and traffic, are rendered darkly dystopian, and often cleared of any living presence.

Most alarming of all is the assumption, expressed in a number of comments in the visitor’s book, that these photographs were taken in an ‘undivided India’, erasing the show’s regional reach and asserting the dominance of the Indian nation state over its neighbours. This perhaps speaks to the audience’s entitlement: many Indians rarely check their privileged position in the subcontinent. And, as the show betrays, rarely does Dalrymple.

William Dalrymple: The Historian’s Eye at Akara Art, Mumbai, 13 April – 3 May

From the Summer 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia