Pinaree Sanpitak’s preoccupation with the female breast underpins a body of work that is graceful, tranquil and almost otherworldly, incorporating but also transcending the limitations of the female breast and its connotations of fertility and the sexual. Sanpitak’s description ‘breast stupa’ was coined in connection with a similarly titled work shown in Fukuoka, Japan, in 2001, the term conflating two concepts: one, the female breast; and two, a Buddhist site of veneration that is also a signifier for the overwhelmingly male monkhood in Thailand (where Sanpitak is from). For more than two decades, the artist has explored these two motifs in works that deploy a variety of materials – from saa fibre to glass, stainless steel to Thai textiles – and span an equally diverse array of media – etchings, paintings, collages, weavings, sculptures, installations, performance and collaborations in the culinary arts, to name just a few. This versatility with materials and forms has come to define her practice.

Breast Stupas (2000–01), shown at Fukuoka’s Seinan Gakuin University Library, comprised 37 largescale silk hangings that revealed an unthreaded elongated breast shape on each panel as the audience walked through the installation. The work triggered comparisons with sculptor Eva Hesse’s 1968 Contingent, and indeed, like Hesse, Sanpitak deploys the idiom of repetition and a minimalist aesthetic. However, unlike Hesse’s oeuvre, Sanpitak’s works – in their exploration of a metaphoric relationship between the stupa and the intimate, sensual, curved shape of the breast crowned by a nipple – oscillate between the sublime and the tongue-in-cheek, the fragmented and the whole. They resonate as the subversive interposition of a personal female consciousness within institutionalised religious realms. Because ‘breast’ is an inherently gendered vernacular, Sanpitak’s distancing of her work from her moniker as the ‘breast artist’ in interviews may come across as coy, particularly given that she has also previously stated that the birth of her son in 1993 and the breastfeeding that followed served as points of inspiration for her predominant motif. Rather than promoting a sense of ambivalence however, her visual expression resists such convenient limitation; one comes away from a viewing of her works with a rich sense of being enveloped in spirituality, nurturance and beauty, informed about female subjectivities but also the workings of the body, both private and public. Two solo shows in Singapore this autumn, at the partially state-funded STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery and at commercial gallery Yavuz, provide an opportunity to reconsider Sanpitak’s oeuvre. The artist describes herself as fundamentally a ‘painter by nature’, and her exhibitions frequently feature her paintings amid large installations. She returns to this medium full force in her show at Yavuz (which consists solely of paintings with collaged elements). Her show at STPI features all new works on paper, showcasing a prolific output that has optimised STPI’s unique print- and papermaking capabilities, which an artist residency there is intended to facilitate.

In 1999 Sanpitak participated in another printmaking workshop, with Northern Editions in Darwin, Australia, which she credited for spurring her further explorations into different media and forms. One of her best-known works, which has spawned different versions, is Breast Stupa Topiary (2013). These three-metre-high breast-stupa sculptures are made with stainless steel (the work was first exhibited as an outdoor installation at Museum voor Moderne Kunst Arnhem, The Netherlands). In 2018 a version of the work was shown at the Jim Thompson Farm in Thailand, functioning there as trellises for vegetal growth, thereby shifting their meaning from confinement to an Edenic idea of regeneration. For her ongoing Breast Stupa Cookery project (2005–) she invites chefs to use her cast-aluminium or ceramic breast-stupa moulds as they see fit, and the results have been inventive. At a staging of the cookery project in Plymouth, New Zealand, in 2011, two participating Maori chefs produced potato yeast bread and other dishes that included berry juice to connote the menstrual flow of women. The project has at times catered to between 200 and 300 people, hosting audiences in Thailand, Spain, China, France, Japan and the us, harnessing the idea of a food gathering as sustenance through a forum for sharing and exchange.

Sanpitak’s works resonate as the subversive interposition of a personal female consciousness within institutionalised religious realms

New versions of both Breast Stupa Topiary and Breast Stupa Cookery are being shown at this year’s Setouchi Triennale, which takes place on the islands within the Seto Inland Sea, Japan. In the former, which Sanpitak has retitled The Black and The Red House, sited in the back garden of an abandoned house on Honjima Island, the artist remade her breast stupa structures with yakisugi charred wood (yakisugi is a traditional Japanese method of preserving wood – charring its surface to make it more durable through carbonisation) as homage to the cultural and historical elements of the site. In another room of the house, set up as a café with red pillows, Sanpitak invited Chef Ramses Yanagida to serve his version of Breast Stupa Cookery – curry, Thai tea and Thai custard. Elsewhere around the island, residents have been serving their versions of Thai food, developed in a Thai cookery workshop Sanpitak and a Thai chef conducted there in May. Key to understanding Sanpitak’s practice is that each new work is part of what she calls a ‘continuously evolving’ process of ‘ideations from previous works’; new works may strike divergent symbolic pathways, but a dialogue with her past works continues.

The more playful and participatory aspects of her work feel restrained at her STPI and Yavuz shows, but Sanpitak’s paintings compensate with their exuberant, compulsive iterations of the fragmented breast shape. Past works such as 120 vessels (2000–01) have analogised the inverted breast stupa shape to alms-bowls. Using repetition as lexicon, 120 vessels featured row upon row of upturned, wide-rimmed bowls, rendered in candlewax and charcoal on paper, drawing upon the Buddhist concept of accreting inner merit through outward gestures of compassion and alms-giving. Sanpitak’s preoccupation with the breast motif calls to mind Yayoi Kusama’s obsession with dots, but unlike Kusama (to whom she has also been compared), Sanpitak’s obsession has less to do with a state of mind and more an engagement with ritual. At STPI, her paintings showcase an extension of the breast and breast-stupa to other biomorphic shapes, such as clouds, seeded pods, aquatic bodies and homologous body parts, ideations she has previously incorporated into her works or of which she has been cognisant. Works in the Breast Talks (2018–19) series show a medley of these shapes, collaged and arranged cheek by jowl on the same canvas, juxtaposing new work with old work, underlining the importance of dialogue and spiritual interconnectedness to her practice.

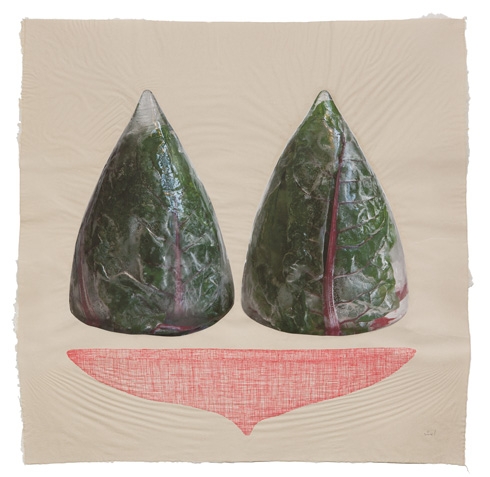

Her STPI artist residency also yielded innovative results. Sanpitak sourced dried ebony fruit from Thailand, which was ground up and mixed with indigo into liquid paper pulp to yield black paint. In one stunning work, Black Dreams I (2019), shown at Yavuz, she paints over collaged-on origami shapes, textile and jute squares, producing intense gradations of black that reveal a metallic sheen and textured depth. At STPI, she also experimented for the first time on linen paper and collaborated on a process of embedding collaged shapes onto paper and then painting over with paper pulp. The resulting paintings looked like seamless canvases with texture and layers rather than discernible glued-on collages. This embedding process produced an eye-catching work in Breast Talks 4 (2018), where a previously made UV archival print of breast shapes collaged onto the canvas resembles glutinous Thai desserts wrapped in lotus leaf.

These three-metre-high, stainless-steel breast-stupa sculptures function as trellises for vegetal growth, thereby shifting their meaning from confinement to an Edenic idea of regeneration

The centrepiece of the STPI show, The Walls (2018–19), is a largescale mazelike installation comprising 100 square paper sheets (all made as part of a collaborative process between Sanpitak and STPI during her 2018 residency), harking back to Breast Stupas. An initial version debuted at the Encounters section of Art Basel Hong Kong in March. Hung from the ceiling, these sheets were patterned with layered and collaged-on geometric forms of various sizes and types. Sometimes these showed signs of peeling or stress marks that had resulted from the various drying processes undergone by the materials, all of which added to the feelings of tactility and depth that were the most interesting aspects of this massive installation. Moreover, an earth-tone colour scheme evoked the idea of ‘skin’, and the paper sheets had a porosity and fragility that presented a subtle tension with the depersonalised abstraction of the geometric shapes. Despite the installation’s wow factor, the cramped feeling and the meanings gleaned from a walk-through – the breach of the public by the private, and the inescapable association of bodies and ‘walls’ to the current political climate – feel tendentious and simplistic, and the ironic note struck against the titles of both the work and the show, which seemed too literal, especially given its scale and spotlight.

Her collagraphed and screenprinted works in bold red, such as Breast Works Red Alert! 4 (2018), shown as a group in a separate section of STPI, and her work entitled Red Alert! My Body My Space I (2018–19) at Yavuz, are striking, perhaps signalling a departure from her usual subdued colour scheme. Sanpitak has stated that her choice of the colour red was to evoke a sense of ‘danger and urgency’ concerning women’s issues, a reflection of current political pressure-points. But rather than a conceptual depth, contemplation of her works in both shows confers an aesthetic joy, brought about by the way in which they revel in the minute variations and interplay of line, shape, size, colour, juxtaposition, texture and method, all of which make manifest the malleability and multiplicity of the breast form.

From the Winter 2019 issue of ArtReview Asia