A new history of art in post-Mao China and a study of the fate of the country’s rural hometowns – reviewed

The Art of Contemporary China is the latest addition to Thames & Hudson’s iconic ‘World of Art’ series. Although Jiang Jiehong politely kicks against the series’ encyclopaedic construction, explaining that his story will be rooted in the particular social and cultural context of post- Mao China as opposed to the world history of art. What this means in practice is that his narrative is structured by themes (art’s relationship to the masses and collectivism; to tradition; to urban transformation; and to a constrained society) drawn, as he puts it, from the ‘everyday reality’ of China, rather than a conventional chronology.

Given Jiang’s conceit, perhaps it’s no accident that the only non-Chinese artist cited in the book – Robert Rauschenberg, who exhibited at Beijing’s National Museum in 1985 – used to claim that his work occupied a middle ground between art and life. Yet, beyond that aside, little attention is paid to outside influence: why many Chinese artists migrated to Europe and the US; the impact of the international artists who currently occupy so much of China’s gallery real-estate. Hong Kong, so much a part of China today, does not exist. Nevertheless, Jiang’s approach is welcome in that it goes some way to explaining why some of the preoccupations of contemporary art in China have developed and allows the author to connect one artistic practice to the next to create a convincing and at times illuminating narrative. And to make a break from the often asphyxiating tendency to divide contemporary Chinese art into strictly differentiated generations, rather than a continuous and messy flow.

Where it falls a little flat is in the fact that not enough space is given to the intricacies of the realities from which the art derives. Indeed, not all of the realities of life in China (the impact – good and bad – of technology, for example) are present. In part this is a product of the state censorship regime in China, but it is equally a consequence of the paradox Jiang has created for himself: in which the real life from which the art is generated can only be identified when it enters the slightly less ‘real’ sphere of art. So, while the approach looks fashionably bottom-up, it is necessarily top-down. The Tiananmen Square ‘incident’ of 1989 is mentioned and a few artworks relating to it, such as Song Dong’s Breathing (1996), glossed; its true impact (and the restrictions governing discussion of it) is never discussed. Even a work as apparently ‘real’ as Hu Yunchang’s One Metre Democracy (2010), in which the artist had himself sliced open for a metre-long stretch from his clavicle to his knee, seems both privileged and indulgent without more contextual focus on what ‘democracy’ – a remarkably shifting value – meant in China at the time.

Similarly, the economic context of both China and the development of the Chinese art market over the past decade or so is one about which Jiang, rather bizarrely, remains silent. Presumably because this avoids complicating his vision by having to deal with contemporary art’s interconnection with the country’s wealthy citizens/collectors, the increasing prevalence of art in government-led gentrification schemes or the influence of art-market forces.

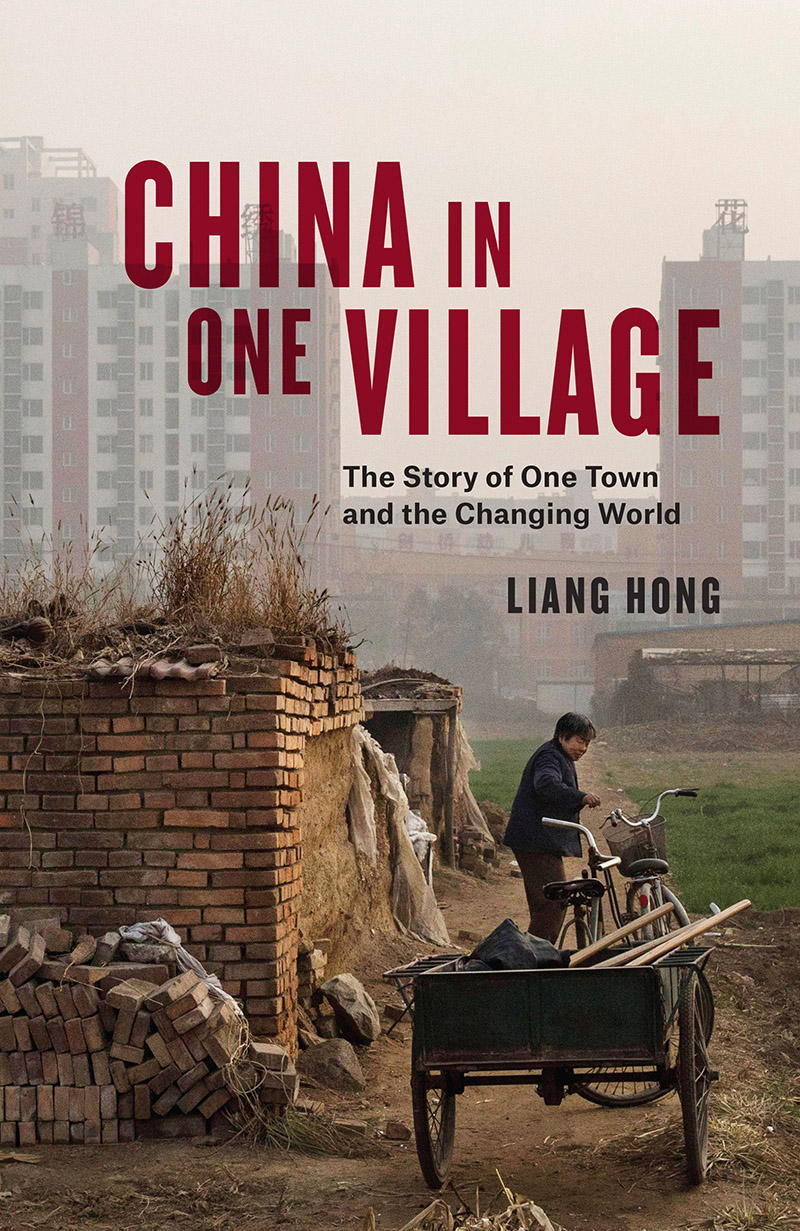

The effects of changes in China’s economic, social and political policies over the same time-frame dominate Liang Hong’s China in One Village, an at times harrowing, but stunningly insightful meditation on the status of the word ‘home’ and the redefinition of the family unit told from the perspective of ordinary citizens in rural China. Based on a series of interviews with Liang’s extended family and other residents of her hometown (Liang Village in Henan Province, Central China, from which the author, a professor of literature in Beijing, had been largely absent for a decade), it was originally published in Chinese in 2010.

With little largescale industry (and the infrastructure that comes with it), the region’s economy, such as it is, is largely agrarian, its fabric torn apart following 30 years of sometimes contradictory ‘reform and opening up policies’ (which saw the decollectivisation of agriculture and an opening up to foreign investment) set in motion by Deng Xiaoping during the late 1970s and stuttering through to the early 2000s. Liang summarises the government assessment of the area as economically underdeveloped, socially conservative and generally backward; and the more general status of the rural population in China, which once constituted the majority of its population and the primary focus of Communist Party policy, as a ‘large burden’ on society, both politically and culturally.

Broadly anthropological, yet coloured by emotion, the book focuses on the lives of three generations of villagers: grandparents dealing with the scars left by the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), their children (the author’s generation) who have left to find better-paid work in more-or-less distant cities (but continue to identify Liang Village as ‘home’ and to show off their wealth within it) and their children’s children, who consequently have little connection to either the town or the country. During the course of this history, the village has become part abandoned, part lavishly reconstructed, its arable soil drained of nutrients by brick factories and other extractive industries that have further damaged the irrigation systems and water quality. Children who moved to urban centres to seek employment rely on their parents to provide childcare services to grandchildren in a transactional relationship that extends the grandparents’ working lives and exploits traditional family structures. ‘In the future will these places [villages] really be their “hometowns”, these places characterised by loneliness, isolation, and contradiction? Lifeless and emotionless,’ Liang wonders in respect of younger generations.

Yet part of the power of this book is the fact that Liang never allows it to become a straightforward sob story: ‘the problem of the under- classes isn’t a simple question of the oppressors and the oppressed; it’s a game of cultural power’, she writes, noting that villagers’ general apathy towards a sense of society outside of the family and village unit, their indifference to national politics and passive acceptance of their fate is partly responsible for their current situation.

What makes Liang’s study so compelling is the way in which it offers a glimpse of a world in which personal problems – among them alcoholism, envy, domestic violence – exist on the same level as broader social and political problems – changes to collectivised structures, village and provincial finances, education and healthcare provision. Which, of course, aligns with Jiang’s conception of the history of China’s art. ‘Literary and artistic works explain life,’ the Rang County Committee Secretary informs Liang. But while China in One Village provides much of the additional contextualisation that Contemporary Art in China needs, how the former benefits from the context of the latter is rather less clear.

The Art of Contemporary China by Jiang Jiehong, Thames & Hudson, £14.99 (softcover)

China in One Village by Liang Hong, translated by Emily Goedde, Verso, £19.99 (hardcover)