Spalding’s memoir, Art Exposed conjures a period in British history when the public debate around visual art was hotly contested

‘When I went to art college conceptualism was already in 1966, beginning to sweep the board. It struck me as fatuous, pretentious, quasi-intellectualism from the start.’ Onetime museum director and writer Julian Spalding doesn’t mince words, and now, in his seventies, he’s still battling for an idea of art that understands making and crafting – rather than writing and theorising – as the main source of visual art’s value. Art Exposed is a memoir of a career running museums during the 1980s and 90s, and then as a broadcaster and critic, told in an ABCD of recollections of artists Spalding has encountered professionally (H is for David Hockney, B is for David Bowie) or officially (Q is for the Queen, T is for Mrs Thatcher), or otherwise still has an axe to grind with – D is for Marcel Duchamp, S is for (former Tate director, and now Arts Council England chair) Nicholas Serota.

For those who were still in babygrows during the 90s, Art Exposed offers a view of a British artworld that doesn’t really exist anymore, but Spalding’s engaging, rambling and digression- filled recollections – about forgotten artists, deceased politicians and all-too-enduring cultural bureaucrats – conjure a period in history when the public value of visual art was hotly contested; in which a tangle of issues – craft versus concept, the old medium of painting against the emerging new media, the influence of the art market and the role of the museum, popular versus elite taste – define a debate over how the public gallery might address a national culture. In this pre-Tate Modern artworld, Spalding recounts Bowie visiting him unannounced: ‘He’d come to see me because he knew about my stand against conceptual art. He agreed with me.’

It seems strange that one of the giants of postmodern pop should have been getting into painting, but then their shared suspicions were really to do with why this new kind of art was starting to turn up everywhere, and what it meant for the value of the artist, the artwork and its public. In Spalding’s recounting of a similar conversation with Hockney, the painter observes dryly, ‘It’s a very un-Duchampian thing to do to re-do Duchamp’. Duchamp, Spalding argues, ‘had great appeal to egalitarians, by… destroying [art’s] exclusivity and making it accessible to everyone’. But ‘it also undermined any attempt to make value judgements about quality in art… Outside observers, curators like me, let alone Joe Public, didn’t have a say.’

Spalding’s decades-long feud with the British artworld ‘establishment’ (alongside other frequently dismissed grumpy old men such as onetime editor of ArtReview David Lee) is really always about a different point – who gets to decide? It might seem ridiculous to read Spalding (at various times head of museums in Sheffield, Manchester and Glasgow) plead himself as the ‘outsider’, but then his form of curatorial populism, and his own working-class South London origins, find him eventually faced with where the real power lies: interviewed for director of the V&A, by former foreign secretary Lord Carington, he’s told curtly, ‘we don’t want anyone with ideas, you know’. Speaking to out-going Tate director Alan Bowness (educated at Cambridge and the Courtauld), ahead of Spalding’s interview for the Tate top job (for which Cambridge-and-Courtauld educated Serota is also shortlisted), Bowness turns and matter-of-factly points out, ‘You do realise this is Nick’s job, don’t you?’

So Spalding is no great fan of Serota, itself no new revelation. But the personal snipes – Serota’s alleged mirthlessness and petty snubs (never being invited to the Tate once Serota took over, Spalding complains) – are hints of the bigger shifts in the public institutions of art in the last two decades: a fixation with power, managerial opacity, the avoidance of public debate. Still, according to Art Exposed, Spalding managed to enjoy himself, inspired by artists and the task of making museums that ordinary people would themselves enjoy; more than can be said, perhaps, of some of his contemporaries.

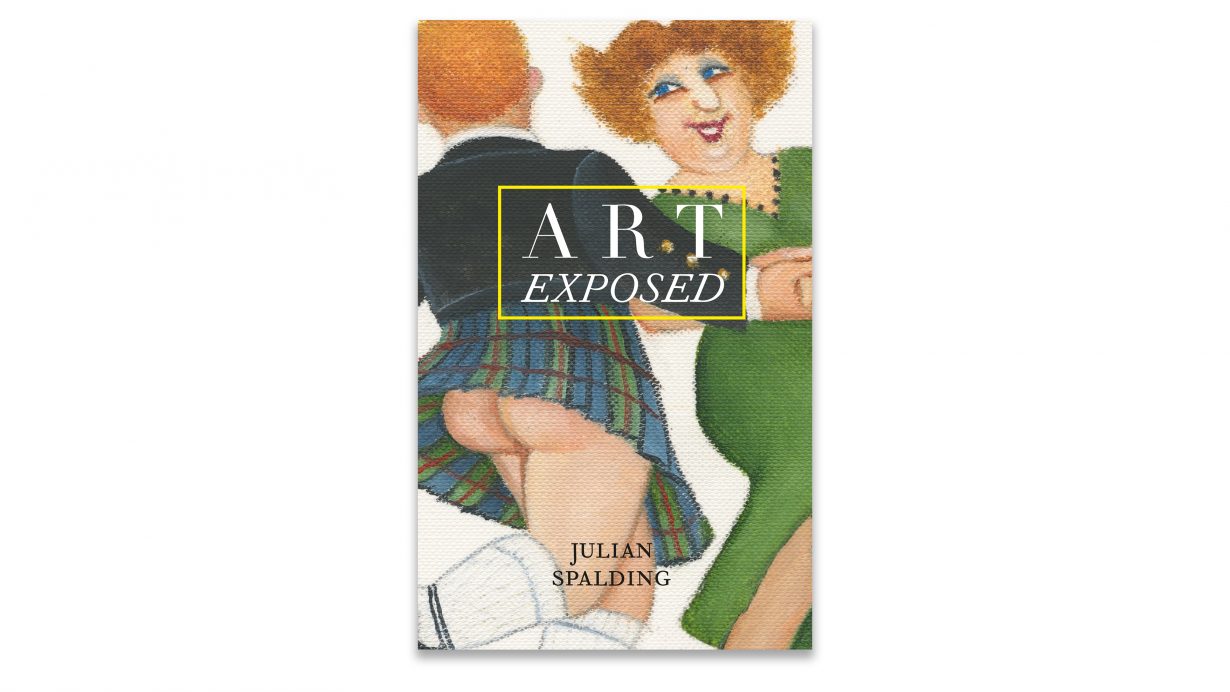

Art Exposed by Julian Spalding. Pallas Athene, £17.99 (softcover)