In his new work, the Armenian director and cult filmmaker – once championed by Jean-Luc Godard – turns his lens towards the realm of ecological disaster

Armenian director Artavazd Pelechian is one of the most visionary artists to have emerged from the Soviet Union, but like several of his friends making cinema in the then-existing republics of the South Caucasus, he struggled to work uninterrupted or breach the margins of canonised world film history. When he embarked on his career during the early 1960s, his near-wordless black-and-white films were way ahead of their time in blending the reality levels of documentary archive and poetic fiction. Their shortness of length and blurring of categories, though, reinforced their status as outliers, resistant to being co-opted and stripped of their arcane mystery by crass marketforces, and unlikely candidates for mainstream popularity. Pelechian has a near-cult core of devotees, and few initiated into the singular, intuitive strangeness of his montage experiments would argue with the evaluation of his contemporary, Georgian-Armenian maverick Sergei Parajanov, that he’s one of cinema’s rare ‘authentic geniuses’. For all that, his name is still rarely heard beyond cinephile circles.

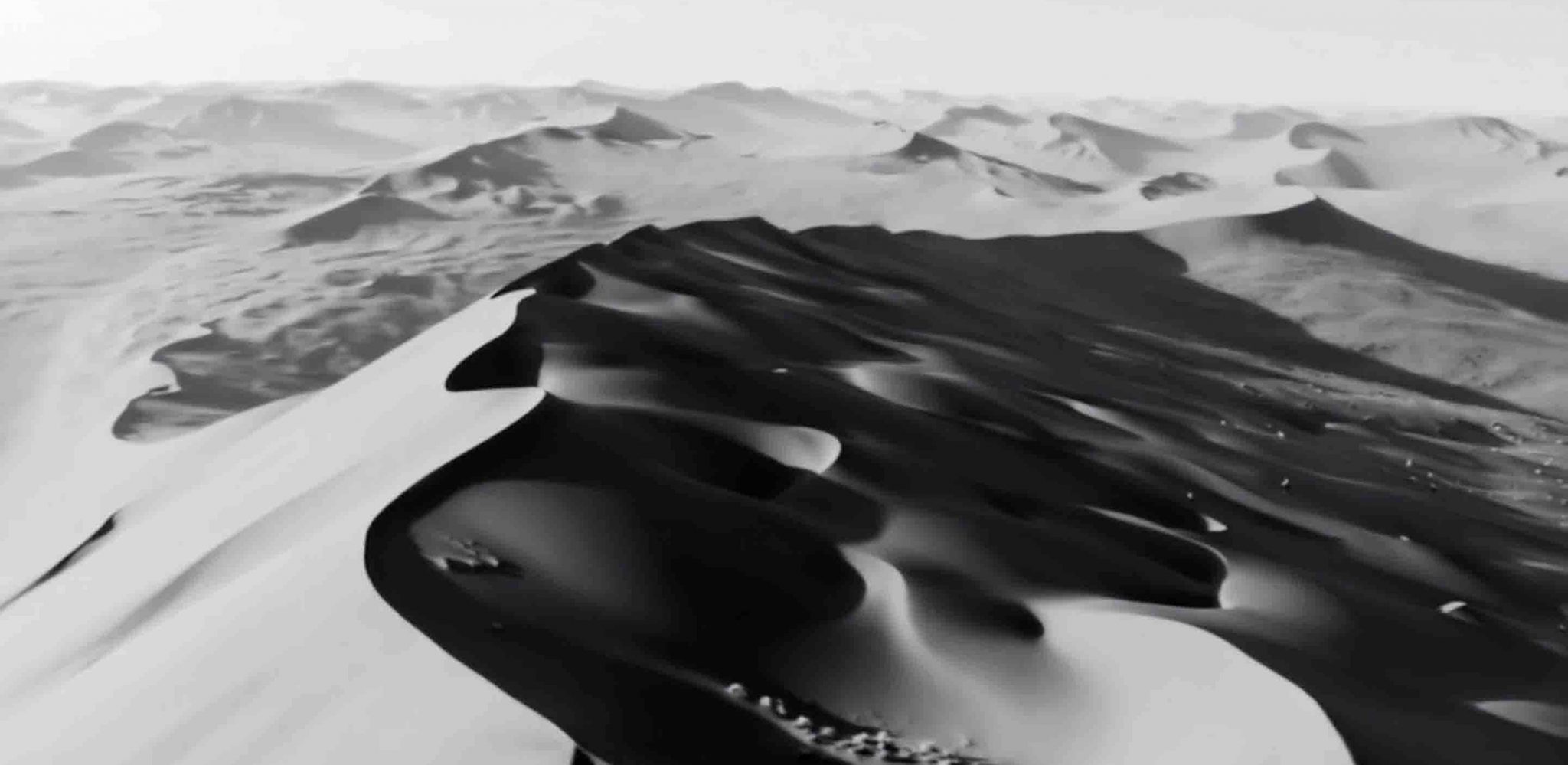

However, interest in him is growing, helped by a new film – his first in 27 years. Nature (2020) is having its world premiere at the Fondation Cartier in Paris (which co-commissioned it with Karlsruhe’s ZKM) currently. It is screening together with Pelechian’s The Seasons (1975), considered by many the greatest documentary ever made in Armenia, and in its rhythmic channelling of the rolling and bursting motion of nature at its most cataclysmic, the new film is as staggering as this earlier work.

Courtesy Artavazd Pelechian

Pelechian, who is now eighty-two years old, grew up in Armenia’s second-largest city, Leninakan (now called Gyumri). There was no cinema, let alone a film school. After working as a mechanical engineer for a while, he found his way, like many budding directors across the Soviet bloc, to Moscow to enrol at famed film institute VGIK. (As well as Pelechian, the school’s illustrious list of former students includes Parajanov, Mikhail Vartanov, Andrei Tarkovsky, Elem Klimov, Larisa Shepitko and Kira Muratova.) The surging movement of crowds and natural forces during states of upheaval and emergency recur in Pelechian’s work, established in his earliest shorts. The Beginning (1967) captures the revolutionary forces of history set in motion by 1917’s October Revolution in a distilled, ten-minute blizzard of 50 years of newsreel footage. We (1967) marks the trauma of the 1915 Armenian Genocide on the Armenian people – a modern cataclysm at that time, still little acknowledged – with a sombre, mesmeric weave of daily life and ritualised mourning. Inhabitants (1970) evokes the existential threat posed by humans through frenzied swirls and stampedes of panicked animals.

Most of Pelechian’s 13 films as director have been shorts (at just over an hour, Nature is an exception). Rhythmic, largely dialogue-free and classical music-driven, they operate at a subconscious level. Time can feel strangely stretched and looped in them, due to the ‘distance montage’ method he developed. Rather than assembling and juxtaposing shots directly beside each other to create meaning, as montage pioneer Sergei Eisenstein proposed, Pelechian separated linked or repeated images, inserting other frames between them so that they would reach back and forward across the film towards each other with reverberating energy, connecting the viewer with a grander-scale cosmic unity that absorbs all difference. ‘For me, distance montage opens up the mysteries of the movement of the universe. I can feel how everything is made and put together,’ he told the film critic Scott MacDonald in 1991.

Pelechian’s work at first hardly travelled, but he has enjoyed special appreciation in France since the 1980s, after film critic Serge Daney saw some of his films on a visit to Armenia and, blown away, wrote a glowing article for French newspaper Libération, declaring the director ‘a missing link in the true history of cinema’. French New Wave pioneer Jean-Luc Godard then became a vocal champion of Pelechian’s work and an eager conversational partner on montage and the essence of cinema, as both sought to push the medium’s possibilities.

35mm b/w film, 29 min. Courtesy Artavazd Pelechian

Artists with local Armenian loyalties and subversive visual flair that departed from state-sanctioned socialist realism were distrusted by Moscow’s authorities, who fully funded and controlled the film industry. Pelechian suffered less overt suppression than his, to some, more abrasively confrontational friends making films in Soviet Armenia. Parajanov has since become the best known, the belated reach of his influence clear in September when Lady Gaga, one of the world’s best-selling pop divas, appeared in the video for her track 911 in sand dunes, blood-red fruit arranged around her, in imitation of the surreal, dreamlike tableaux of The Colour of Pomegranates (1969), Parajanov’s esoteric masterpiece on the life of eighteenth-century poet Sayat-Nova and the resilience of Armenian culture to attempts at violent erasure. After Mikhail Vartanov was blacklisted and fired from directing at Armenia’s sole film studio for making The Color of Armenian Land (1969), a film about dissidents Parajanov and painter Minas Avetisyan, and for speaking out against Parajanov’s 1973 arrest and imprisonment on charges including homosexuality, Pelechian successfully lobbied to have Vartanov work with him as a cinematographer – a collaboration that resulted, during the mid-70s, in The Seasons.

The Seasons is a mesmerically odd, lyrical and disquieting work of orbital echoes, in which the forces of life and death entwine closely. Farmers shift their sheep for feeding up and down mountainous terrain in step with seasonal changes, clutching them tight as they tumble over each other almost as one down snowy inclines, and through river rapids that buffet and draw them under. In summer comes harvest, and the motion is echoed, as workers roll clumps of hay down a hillside. Textural splendour resides in the glittering creases of men’s rain-lashed coats and other details worked over by the elements, even as we sense the relentless energy required to survive, and submit the self to its place in nature’s forcefield. It’s astounding that a film so chaotic and perilous can feel at once so organically harmonious. It’s all in the tumbling rhythm as humans and animals navigate a nature unleashed full-tilt, and gravity at its most unforgiving. ‘Do you think it’s better elsewhere?’ asks one of several sparse intertitles, reinforcing a sense of human universality to events in a film with few language-based signposts.

35mm b/w film, 29 min. Courtesy Artavazd Pelechian

It’s impossible to know what Parajanov, who died 30 years ago, would have made of the recontextualisation of his work into cheeky pop-culture images viewed on laptop and phone screens. Pelechian’s early work remains as inscrutable and outside the mainstream as ever, but he seems to have nimbly adapted to our digital, cut-and-paste era of repurposed borrowings, having culled the footage for Nature from the internet. For a filmmaker with an uncompromising perception of the magnitude of time, it shouldn’t surprise us that he germinated the feature for just as long as it took – 15 years since its commission. Or that, as an editing innovator who has always blended archival material with self-shot footage, he’d be unfazed by the virtual realm as a raw material source equal to others; as just another part of a cosmos that transcends all division of forms.

Rolling, swirling, crumbling: the natural environment refuses static permanence in The Seasons. Through a restless eye that soars and glides, Nature pushes this recognition of topographical instability further, into the realm of natural disaster. The fragile harmony of our ecological interdependencies are increasingly fraught in days of climate crisis. In this film of speed and force, crumbling glaciers and avalanches redefine the contours of a world in flux. Volcanic eruptions spew liquid heat, tornadoes rip out sturdy trees and tsunamis claim fleets of cars from washed-out bridges and roads, as melting and drowning fluids encroach, architectural structures collapse and explosions billow skyward, remaking terrain’s foundations.

In this maximalist visual symphony, soundtracked by Beethoven, Mozart, Shostakovich, Avet Terterian and Tigran Hamasyan, nature’s cataclysmic forces upend human habitation, perched precariously on land that is still for just a relative second of the planet’s billions of years of history. The sheer destructive might on show defies comprehension, let alone control, amid its terrible beauty. But morning breaks again. And if anything can contend with the ineffable, it’s filmmaking, according to Pelechian. ‘I am convinced that cinema can convey certain things that no language in the world can translate,’ he said in 2000, comparing it to the Tower of Babel; to before the world was drawn apart by languages. A cinema that trusts in unity’s eternal renewals out of chaos and heaving disruption may be just the salve for our treacherous times.

Carmen Gray is a film critic, arts journalist and curator based in Berlin

Artavazd Pelechian, Nature, The Seasons, is on show at the Fondation Cartier, Paris, through 7 March 2021