At Wanås Konst, Sweden, the artist’s project ‘Sowing into Painting’ returns culture to nature

While most people were locking down this May, Korean artist Kimsooja was hanging out laundry, in a wood northeast of Malmö, not too far from the border between Sweden and Denmark, on the site of a medieval castle and an organic farm. Between the trees, 100 pristine white bedsheets are pinned to clotheslines and flap, like so many captured cartoon ghosts, in the wind. They give an idea of stains removed, fresh starts, new beginnings, extreme hygiene and slates wiped clean. And, with their embroidered trims (an example of local craftspersonship), of old traditions of manufacture and housework, which to a lot of us might seem anachronistic in a world of urbanised living, rapid manufacture, household convenience and washing machines. White: the mark of mourning, purity and rebirth. Or perhaps all this is to overthink what is simply evidence of an easily comprehensible, quotidian routine.

But overthinking is a pastime in which many of us have had an opportunity to indulge over the past few months. Locked down, changing our routines, afraid of other people, afraid of going out, conjuring profundity out of banality and, egged on by politicians around the world, constantly redefining what we mean by ‘normal’. As if the term was anything other than subjective in the first place.

The sheets make up an artwork titled A Laundry Field (2020). If that ‘A’ before ‘laundry field’ suggests that it is one of many, it is. And in more ways than one. On the one hand, because what we see is nothing new: many people around the world hang out their washing to dry; they’ve been doing it since they had things to wash, and things to hang them on. If you stumbled across the washables here, at Wanås Konst, you’d be forgiven for thinking that it was simply evidence of a routine interrupted by, say, a sudden global health emergency meaning that no one was around to take it in. On the other hand, A Laundry Field is a development of earlier works by Kimsooja, such as Mumbai: A Laundry Field (2007–08), a multi-channel video that uses footage of the city to cast the overcrowded Maharashtra port as a field inhabited by people wearing clothes and people cleaning or drying clothes. Both works play with their ‘matter-of-fact’ nature and are evocative in their banality, their normality and the ways in which they accept – but do not insist on – projection and interpretation on the part of the viewer. You want to see garments as embodying the history and traces of human bodies? Fine. You just see ordinary life? That’s a truth too. It’s a form of equivocation that lies at the heart of much of Kimsooja’s work. And, you might say, at the heart of much good art. ‘I saw art in life and life as art,’ the artist said in a 2008 interview with Susan Sollins. ‘I couldn’t separate one from another. So my gaze to the world and my questions were always related to life itself.’

Kimsooja’s best known works feature bottari, a traditional Korean cloth bundle used to wrap goods in preparation for transport by hand. While such fabrics (bottari are often recycled from colourful bedspreads) have acquired links over time to the gendering of labour, the dynamics of domestic and civic power and the segregation of public and private space, bottari bundles are also evocative of displacement and migration (frequently, and particularly in terms of Korea’s modern history, as a result of war and famine), symbolic of both the home and a lack of one.

Although this interest is born of the artist’s Korean cultural heritage – her own ‘reality’, as she puts it – it developed as a medium to be used in more than just two-dimensional works (the artist trained as a painter) when she was displaced from that heritage, during a 1992 residency at moma ps1 in New York. There, the museum became a space in which to accept the bottari’s cultural baggage and to subvert it. In the resultant installation, Deductive Object, she inserted fragments of Korean bedcovers into gaps in the gallery’s brick wall and made static sculptures out of a series of everyday objects covered in bottari cloth. Over the years the bottari works have developed simultaneously as a reality and an abstraction, similar to the way in which civic and social culture across the world has drifted these past few months. Cities on the Move – 2727 Kilometers Bottari Truck (1997, first shown in the group exhibition Cities on the Move, from which the work’s title derives) was a performance and video documenting the artist’s 11-day journey across South Korea, visiting places with which she had a personal connection, on the back of a truck overloaded with tied bottari bundles; To Breathe: A Mirror Woman (2006) saw her clad Madrid’s Crystal Palace in translucent, light-refracting film in such a way that the building itself and the atmosphere within it became a colourful wrapping, a type of bottari.

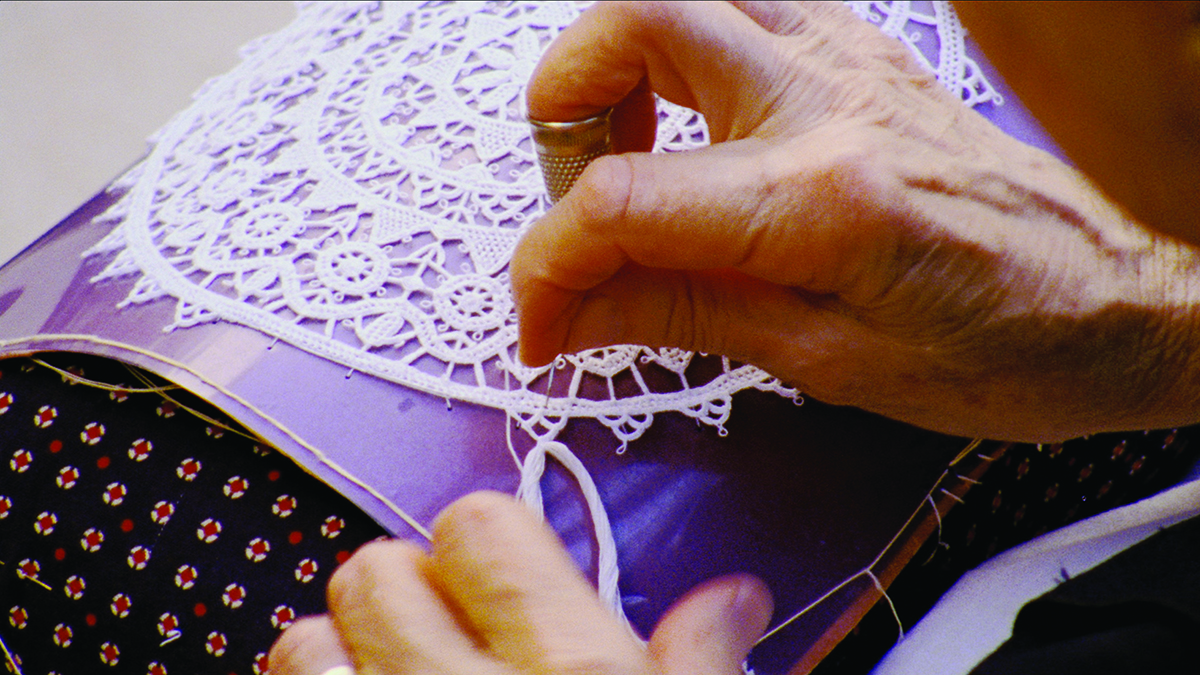

At the same time Kimsooja has expanded such interests beyond her own cultural inheritance in works like the ongoing Thread Routes (2010–), a series of videos inspired after witnessing traditional lace- making in Bruges in 2002. Taking the performative elements of local textile cultures as its subject, the first focuses on Peruvian weaving and the relationship it has with issues of tradition, gender, historic and vernacular architecture, and local landscapes. Further chapters have explored European, Indian, Chinese, Native American and Moroccan practices to create a body of work that further evokes relationships between the particular and the universal, and brings to mind the poetry of mystics such as Kabir. A fifteenth-century Muslim weaver from India, Kabir linked the process of textile manufacture to meditation on and exploration of the divine in his verses. Indeed, they proved to be so successful and easily comprehensible that his influence spans both Islam and Hinduism, and the practices of Bhakti and yoga. Works by Kimsooja such as To Breathe: A Mirror Woman and the interactive installation Archive of Mind (2016) have featured recordings of the artist’s own breathing as components of the installation, while she refers to the videos that make up Thread Routes as a form of “visual poetry”.

Courtesy the artist

“The reality of myself and my culture has constantly and gradually evolved, and rather dramatically since I moved to New York,” the artist writes as we exchange emails between London and Korea and their respective lockdowns.

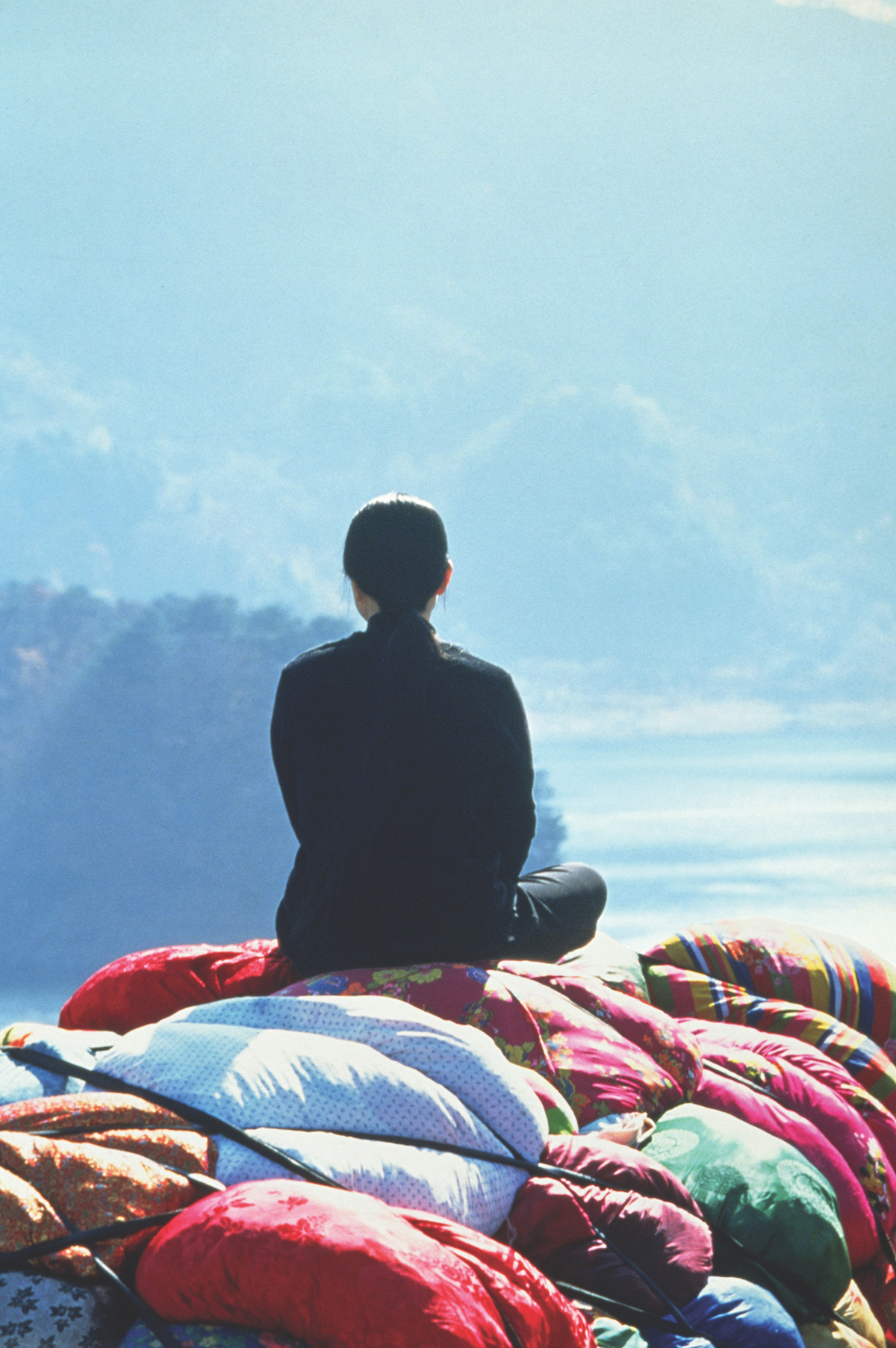

“This move gave me the perspective of my own culture as part of a multi-cultural context. Yet, I held the string of my particular personal life as a continuum that questions fundamental and existential problems: what Zen Buddhism describes as ‘Wha Du (in Korean, Gong An in Chinese)’. This might have given me the consistency and long breath in my career.” She’s referring to the practice in which a story, statement or question is used to provoke a crisis of doubt in the mind of a student of Zen on their pathway to enlightenment. And perhaps nowhere in her work is such a crisis evoked more than in the video series A Needle Woman (1999–2001). In it the artist, clad in grey, is recorded, standing motionless, her back to camera, generally against the flow of traffic, in some of the busiest pedestrian junctions in some of the most densely populated metropolises in the world (Shanghai, Tokyo, Mexico City and Delhi). It’s a work that explores the ways in which losing yourself is linked to finding yourself, about the individual and the collective, and one that has added resonance now that crowds are a source of added fear. The last is something the Nobel Prize-winning writer Elias Canetti described as ‘the touch of the unknown’ in his 1960 analysis of relations between the self and others, Crowds and Power. Although one of Canetti’s assertions – ‘It is only in a crowd that a man can become free of this fear of being touched. That is the only situation in which fear turns into its opposite’ – is looking a bit shaky right now.

“Artists often discover the art in daily life,” the artist writes, “and bring daily life to the museum to contextualise it within art history.” Indeed, even before the intrusions of urinals and readymades and the age of modern art museums, attempts by the authors of poetry (whether visual or written) to engage with the unauthored poetics of everyday life have enjoyed a rich history, not least in painting, and works by Joseon artists such as Danwon, or the seventeenth-century Dutch masters. Yet on the site of the museum there is often a question about what – between daily life and art history – is contextualising or responding to what. And an anxiety about whether it is the artworks in a museum or the circumstances of lived experience that gets audiences closer to truths about the world. All of which responds to a more general paranoia that what enters the museum is removed from lived life. And perhaps it’s a paradox of museum culture for artists like Kimsooja that the more she has sought to introduce the ordinary, the more her work is celebrated as extraordinary.

As we discuss A Laundry Field, Kimsooja explains that her works have been shown mostly within the museum context, but for a few exceptions. “In museum spaces,” she writes, “I used fans, lights, and sounds to give a vibration to it and bring sensation to the audiences as they encounter the persona of the fabrics. When situated within nature, such as Wanås sculpture park [the Swedish foundation is located in a natural landscape], the wind, light, cast shadows of trees, and bird sounds paint the laundered bedcovers and evoke the memories and poetics of the bedcovers. I find A Laundry Field installed at Wanås sculpture park gives an experience that blurs the boundary between daily life and the museum context that maximises the audience’s imagination and experience.” Reading this, it’s hard not to think of the new work as an attack on the exceptionalism of the museum context.

In that, the exhibition at Wanås, titled Sowing into Painting, goes a little further than other works by Kimsooja. It traces a circle through her varied output (it contains chapters one, two and four of Thread Routes, a series of the Deductive Objects (1993–2020), Meta-Painting (2020, which comprises stretched and frame linen canvases as well as bottaris made of linen canvas and used clothes) and To Breathe (2020, an evolution of the work shown in Madrid). And it traces a circle through the manufacture of painting in the title work Sowing into Painting, a field sown with two types of flax that are harvested to produce canvas and other fabrics as well as the linseed oil that is classically used as a binding agent in Western painting. It returns the exceptional to the normal, culture to nature, and a life observed (not least in the types of paintings of ‘everyday’ life that populate museums and other archives) to a life lived.

Kimsooja’s exhibition Sowing into Painting is on show at Wanås Konst, Sweden, until 1 November